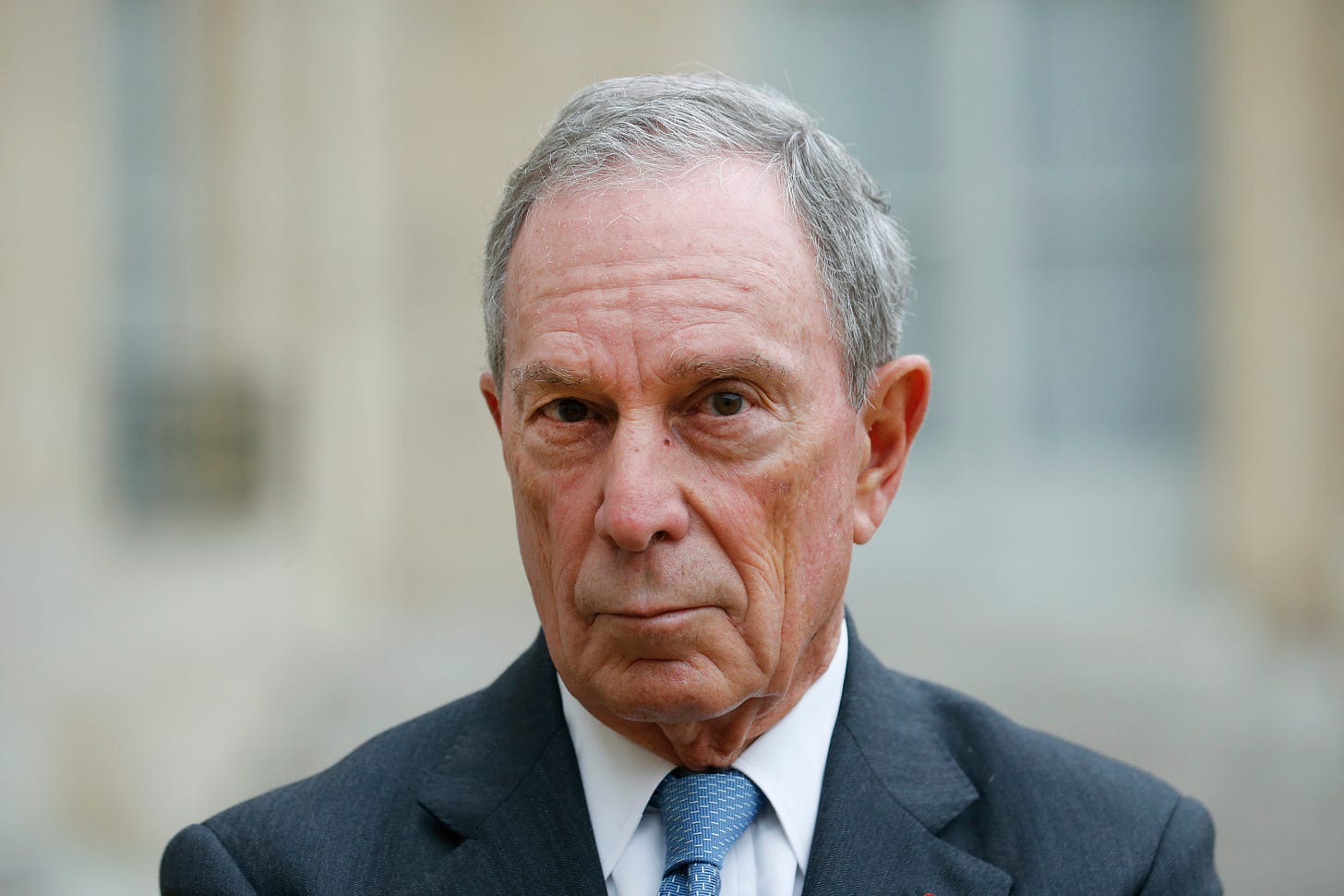

Ultra-Rich Candidates Are Bad. People-Powered Candidates Are Worse.

1. Bloomsday

Mayor Mike takes the stage tonight in what will be an in-kind donation by the DNC to Bernie Sanders. In a sane world, this would be the moment when the entire field pointed at Bernie Sanders and then turned to the camera and asked Democrats, "You really want to do this?" And then opened their oppo books on him. Instead, we're most likely going to get an evening of everyone fixating on the new guy, who has precisely zero delegates and has yet to collect a vote. You can understand why it's happening this way: Attacking Bernie carries the risk of making his people very angry. Bloomberg doesn't really have people yet, so these are free shots. But it's also kind of insane. It's like fixating on the possibility of an earthquake three months from now while your house is on fire. You deal with problems as they present themselves. Whatever. I want to talk for a minute about my conflicted thoughts concerning money in politics. On the one hand, I'm a commie and rich people make me nervous because they often seem to think that the only way people get very rich is by being very smart. Which may be true in some instances, but is not universally the case. A story: Several years ago I met with a Very Rich Man. He was pleasant and kind and well-meaning. I liked him a lot. We were talking about the economic vulnerabilities of the American middle-class. Here is how he explained the problem to me:

Let's say you're an average person. Nothing special, you don't go to Harvard. Just a normal, 50th percentile person with a normal job. By the time you're 30 you've made, what, a million dollars? The problem is that people don't know how to invest that money anymore.

I'm not making this up. I smiled and nodded along because this wasn't a discussion so much as a lecture. And I thought to myself, "How in the world did someone this foolish wind up this rich?" And then I remembered: He inherited it. When you get rich people in politics you get things like Donald Trump telling supporters that he'll pay their legal bills if they want to punch a protestor, or Mike Bloomberg as mayor telling New Yorkers that if they can't afford New York City real estate prices, then it just means they have to leave the city. Money can create a reality-distortion field. On the other hand, on this week's Commentary podcast, John Podhoretz talked about the relative civil peace in Bloomberg's New York, because Mayor Mike basically paid off every activist group that normally makes trouble. From a purely utilitarian standpoint, this seems almost ideal. Most activist groups exist as fundraising rackets. If the facts on the ground are reasonably good, they have to raise money somehow. Bloomberg just cut out the middle step where they raise hell and try to agitate voters by paying them himself. You can see how this could go badly: If New York City had been a hellscape under Bloomberg, then buying the silence of well-meaning critics would be terrible. But times were good and all he was really doing was paying protection money to the kinds of groups that are not especially well-meaning. That's pretty efficient! But also there's this: Let's not romanticize the beauty of small-dollar, people-powered campaigns. Because while money in politics lets guys like Bloomberg happen, when you leave it up to The People, you get guys like Trump and Bernie Sanders. You might not like Bloomberg. But it's not obvious that what his money is buying is worse than what The People are choosing.

2. This Time Is Different

I got an email from a buddy explaining why you can believe that the president has to have confidence in his NSC, but also that what Trump did to Vindman is different:

NSC staffers and ambassadors occupy extraordinarily sensitive positions in which they serve at the pleasure of the president. In 1986, as details of the Iran- Contra affair emerged, Oliver North was quietly reassigned from the White House to Headquarters Marine Corps in Arlington. He was, as we say in the trade, stashed. By the time of the 1987 congressional testimony that made him famous, he had been stashed for several months, and remained so until his retirement from the Corps in 1988. The principle that staffers in whom POTUS lacks confidence can’t be kept on is both long-established and obvious. What was different this time was the ritualized theater of humiliation. The simultaneity of the firings, with its Michael-Corleone-at-the-baptimal-font vibe. The reassignment of LTC Vindman’s brother, reminiscent of the Rodney Dangerfield line “The football team at my high school, they were tough. After they sacked the quarterback, they went after his family.” And, of course, the perp walk. When Oliver North became a liability he had to go, but it’s impossible to imagine the Reagan White House arranging for the press to photograph him being escorted out by security. Another difference from Iran-Contra: North’s family, like Vindman’s, was moved into on-base quarters for security. But the threats then came from foreign terrorists. Now they come from domestic supporters of the president. Because America is now Great Again, I guess.

That strikes me as about right.

3. Shame and Baseball

Paul Lukas, who runs the great blog UniWatch, has a very good essay about shame in sports:

Although [Manfred] didn’t use that word himself, media coverage of his press conference has used it quite a bit. There have been headlines such as “Manfred Says Astros’ Shame Is Penalty Enough” and “Rob Manfred Says Public Shame Is Enough Punishment.” Similarly, articles have included passages like “Manfred said they are being punished through public shame, essentially” and “Manfred … wants fans to believe that a collective walk of shame throughout the 2020 season will suffice as punishment.” The funny thing about this is that I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how one of the defining characteristics of our current historical moment — maybe the defining characteristic — is lack of shame. Over and over again, we see well-established social and cultural standards of behavior, decorum, and right vs. wrong (or at least they seemed to be well-established) being transgressed, cast aside, or just ignored. Sometimes, as in the case of the Astros, the standards were codified into written laws or rules. But more often, they were just agreed-upon norms of behavior that evolved over time, with the shared understanding that most people would not violate those norms because that would make them subject to shame. Those norms are now becoming irrelevant, as shame has turned out to be a fairly impotent force in contemporary life. There was once a collective notion of “You can’t do that” that held certain types of behavior in check, but now an increasing number of people have decided, “Yeah, actually, I can do that” — and it turns out that if you don’t have shame, there’s little if any price to be paid. We see this throughout our public discourse, including our political discourse. If you’re called out on a lie you told, just double down on it and tell it again; if you’re found to have engaged in a despicable act that once would have made your public role untenable, just power through the backlash until everyone has either forgotten about it or gotten too exhausted to care anymore. Shame? That’s for chumps and suckers. (This approach has now become so routine in most areas of public life that I was stunned when the Mets recently cut ties with manager-for-a-minute Carlos Beltrán after the extent of his involvement in the Astros’ scandal became apparent. I figured they’d just power through it until the storm subsided and everyone else would eventually shrug their shoulders.) . . . In the sports and uniform worlds, shame and shamelessness come up on a variety of fronts. Here are a few recent examples: • North American teams and leagues have no doubt looked at their counterparts from other regions of the world for many years and thought to themselves, “Dang, I wish we could put sell ad space on our uniforms like they do!” The reason none of them did it for so long was, essentially, shame. Everyone, including the fans, understands that there’s no good reason for ad patches except greed, and greed is shameful. The NBA was the first league to say, “Eh, you know what? The hell with shame — we’re going to do it anyway.” So they engaged in a shameful act that violated a long-established norm and have paid relatively little price for it. . . . But I don’t want to make it sound like pushing the boundaries of shame is always a bad thing, or that behavioral norms should be set in stone. The threshold of what is or isn’t considered shameful — which usually correlates with what is or isn’t considered outrageous at a given cultural moment — is constantly in flux, and that’s often a good thing. At one time, for example, it was shameful for a man to cry, or for a woman to drink in a saloon. In the sports world, it was shameful for a football player to take himself out of a game if he was dizzy after a hit. I hope we can all agree that it’s good to have moved past those old behavioral norms. . . . If past eras have seen the weaponizing of shame, it seems to me that what we’re now seeing is the weaponizing of shamelessness. Let’s use a military analogy: In war, it’s usually understood that there’s a fear of death on both sides — that’s an assumed behavioral norm. But suicide squads, like the kamikazes in World War II, disrupt that norm. If you’re not afraid of death — indeed, if death is actually your goal, as it was for kamikazes — you’ve basically given yourself a superpower that can be very difficult to counter. Similarly, if people no longer feel bound by shame, or by the shared behavioral norms that shame has traditionally governed and enforced, that too is a tremendous superpower, one for which I don’t think we’ve yet found the Kryptonite. Basically, if you can engage in terrible behavior — behavior that would normally be subject to “Hey, you can’t do that!” — and still look at yourself in the mirror the next morning while the rest of us would cringe at the very sight of ourselves, that’s a very powerful advantage. That’s the weaponizing of shamelessness.