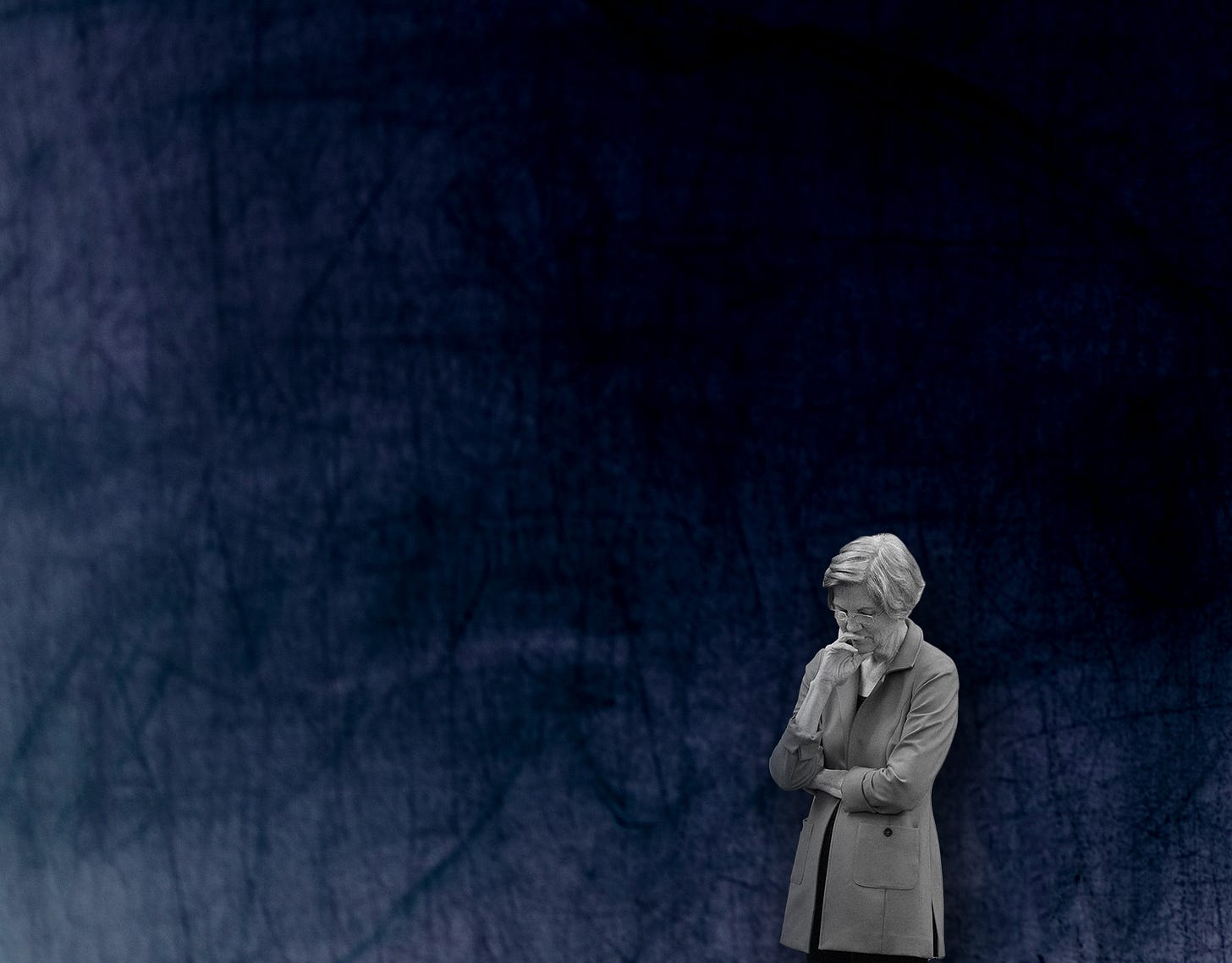

By common consensus Elizabeth Warren is leaking oxygen, floating back to earth after three months of diminishing polls and fundraising precipitated by serial struggles over single-payer healthcare. Now she's foreclosed from campaigning by the Senate impeachment trial. Should she become an also-ran in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada—presaging a crushing loss in South Carolina—a month from now her campaign will be past history-in-the making.

One cannot absorb this baneful forecast without a sense of promise lost—for her candidacy, her party, and a political system denied a more transformative, but grounded, vision of economic and societal change than what is offered by Bernie Sanders' fantastical political revolution.

As a matter of substance, Pete Buttigieg’s fate barely matters. Warren's does.

In its Solomonic editorial endorsing both Warren and Amy Klobuchar, the New York Times saw Democrats as torn between extremes: "Some in the party view President Trump as an aberration and believe that a return to a more sensible America is possible. Then there are those who believe that President Trump was the product of political and economic systems so rotten that they must be replaced."

By suggesting that this somewhat oversimplified choice pits the "realist” (read Klobuchar) against the "radical" (that's Warren), the Times obscures the crucial difference between Warren and Sanders, and, thereby, slights her distinctive effort to chart a singular progressive path which—through considered and detailed proposals—sought to replicate the restorative power of the New Deal.

In crucial ways, Warren is as different from Sanders as she is from Klobuchar. Her failure to define that divergence more clearly—in essence, to escape Sanders' ideological force field—has hobbled her chances in the present and limited our choices for the future.

Sanders' vision is rooted in an alternate reality: a notional mass movement to realize "democratic socialism" through an unprecedented centralization of federal power over the economy along uncompromising ideological lines. That's not Warren.

Rather, she's an avowed believer in free markets who wants to reinvigorate American democracy by reconciling the enlightened long-term interests of capitalism with the needs of Americans at large. That means expanding economic opportunity, reinvigorating competition, and rescuing contemporary capitalism from its potentially fatal excesses by broadening our idea of corporate responsibility. Like Franklin Roosevelt, she seeks reformation, not reinvention.

To accomplish this Warren proposed two pathways. The first adopts the traditional liberal curative of federal spending to improve the lives of the non-privileged. The second evokes Teddy Roosevelt—rigorous regulation to make the marketplace more accessible, and democracy more inclusive, by curbing unchecked corporate power.

It is true that Warren and Sanders have areas of overlap which have obscured their ideological divide. Their diagnosis of our core problem is similar: a system which has concentrated disproportionate economic and political power in our most wealthy citizens and corporations. In the area of tax-and-spend, their programs for free college, student debt relief, and—until recently—healthcare, tended to blur together in the public mind, as do their plans to raise taxes on the wealthy.

Yet even here they differ. Whether one accepts her numbers, Warren is scrupulous about spelling out in detail how she would pay for her proposals. As befits one for whom dreams transcend means, Sanders finds such details beneath him.

But the major difference is philosophical, and defining: what Elizabeth Breunig calls "regulation versus revolution."

Warren wants to liberate our markets from the stranglehold of wealthy interests who warp its functions and appropriate its benefits to their own narrow ends. In this view, a fair and competitive marketplace imbued with social responsibility can optimize competition and broaden opportunity; the role of government is to insure those conditions.

Sanders wants government to be the omnipresent provider and guarantor of lifelong economic security for all. He would bypass markets altogether—creating a web of centralized programs which wed the citizenry at large to a federally-guaranteed "right" to security in almost every aspect of their lives, however well or badly they function—or inescapable and costly they become.

In stark terms, Warren believes in reforming our economy to benefit all without seeking to run it; Sanders believes that only government will do. Warren has already willed an example of her vision into law: the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which helps safeguard consumers from being cheated. In his 30 years in the U.S. Congress, Sanders has done nothing of the kind.

In short, Warren is driven by proven facts and specific policies; Sanders by broad aspirations unmoored from detail and powered by a passion for the unrealized—and currently unrealizable—ideal of a mass demand for an unprecedented, governmentally-directed overhaul of segments of the economy critical to our daily lives.

In an ideal campaign, these differences would be articulated to the enlightenment of all. In reality, Warren fell victim to the toxins of modern American politics in a balkanized electorate: extremism, unreason, and litmus tests of purity divorced from political pragmatism or common sense.

Warren's grand design was to win over Sanders supporters on the left while appealing to conventional liberals and moderates by showcasing thoughtful, detailed policies—enhancing the prospect of unifying the party and appealing to the general electorate. But here she encountered a lethal problem: to propitiate Sanders devotees as adamant as their leader, she felt compelled to embrace his signature proposal—the electoral poison pill of single-payer healthcare.

One need not unduly reprise the fateful outcome. For good reason, remaking the entire healthcare system was never Warren's comfort zone—she knew better, and it showed. Under pressure, she veered from venturing a nonspecific "I'm with Bernie"; to (unlike Sanders) detailing how she would fund her version of single-payer; and, when that boomeranged, proffering a more gradualist approach which pleased no one. Sanders' dead-enders taxed her with impurity; her competitors on the right for concocting serial boondoggles which, in the end, would still deprive Americans of private health insurance.

And here resides the grandest irony:

The most rational of candidates was undone by her transparent efforts to navigate the unreasoning fervor of an unyielding minority for an uncompromising vision which, if adopted, would likely doom any Democrat in a general election.

Yet given that the coalition Warren needed to build started by competing with Sanders for progressives, she felt as though she had no alternative.

But the tortuous path she took bled support on both sides, tarnished her aura as the principled master of policy, and intensified misgivings among the many primary voters focused on electability. So here she is now, hostage to impeachment a few days from the Iowa caucuses, unable to conduct the around-the-clock campaign which might revive her prospects.

Yet her last few weeks on the stump have suggested what might have been. Increasingly, she stresses programs more widely appealing than single-payer to popularize a vision of government which offers concrete solutions to real problems:

Forgiving a big chunk of student debt

Providing childcare and universal pre-k

Reducing the cost of technical school and college

Lowering the price of subscription drugs

Expanding access to Medicare

Increasing the stock of affordable housing

Passing a wealth tax to help fund these programs

Compelling corporate free riders like Amazon to pay taxes

Protecting labor unions to empower working people

Combating climate change and investing in clean energy.

Nor does she stint regulation and reform. She has been highlighting laws to curb the lobbyists who protect special interests and the officeholders who help them; to prevent quasi-monopolies like Facebook from killing competition, peddling private data, and monetizing misinformation; and to discourage corporations and the wealthy from purchasing public policy.

Stressing these issues, Warren argues, replaces the "old left-right division" by asking why America isn't fairer to more people. As she inquired of the Times editorial board: "Will we begin to talk about a democracy that doesn't just work increasingly for a slimmer and slimmer slice of the top, or will we start to talk about a democracy that works for all of us?"

In person, she remains the most compelling candidate in the field: energetic, personable, accessible, smart, and persuasive. She is a thinker who can translate policy into action. In the estimate of the Times editorial board, she still has the capacity to unify:

Senator Warren is a gifted storyteller. She speaks elegantly of how the economic system is rigged against all but the wealthiest Americans, and of “our chance to rewrite the rules of power in our country…” The word “rigged” feels less bombastic than rooted in an informed assessment of what the nation needs to do to reassert its historic ideals like fairness, generosity and equality.

As have others, the Times admonishes that Warren should find a more inclusive tone. Still, the paper concludes:

There are plenty of progressives who are hungry for major change but may harbor lingering concerns about a messenger as divisive as Mr. Sanders. At the same time, some moderate Democratic primary voters see Ms. Warren as someone who speaks to their concerns about inequality and corruption. Her earlier leaps in the polls suggest she can attract more of both.

But at this late date can Warren rise to unify enough of the party to surpass her rivals? A daunting task. Yet until she was sidelined, she was giving it a shot, with more ammunition than some realize.

Her recent claim to be the most "electable" candidate has surprising substance. To start, she has a sneaky breadth of popularity: polls show her to be the consistent backup choice of those who currently support the other Democratic front runners—people who say that they would be "least disappointed" if she were the one to beat their favorite. She has begun decrying the "factionalism" which hurt the party in 2016—and which many fear again.

She is broadly liked among party regulars. Says the former press secretary for Kamala Harris: "She has gone above and beyond to convince establishment types that she is a team player and a Democrat. I don't think they see her as a left-wing extremist, and they respect her seriousness and policy chops."

Polling shows that she bridges generations, drawing support from younger and older Democrats alike. She has reached out to her former rivals—Julian Castro is now campaigning for her—and worked to incorporate some of their policy proposals.

Her peers appreciate her inclusive approach to crafting legislation. Says Representative Raul Grijalva, a former Sanders supporter. "[S]he brings people in." Her thoughtful policy proposals are widely popular among progressives. But she can drive them home to an audience by relating specifics to her own working-class background.

She has a wider cross-ideological appeal than many of her rivals. As the New York Times put it, "backers of opposing candidates would be quicker to reconcile themselves to Warren then to any of the other front-runners. A Warren candidacy would not force centrist Democrats to make their peace with socialism nor ask young socialists to jettison their dreams of egalitarian economic transformation."

All of which gives her a purchase on bridging the party's divisions—a glaring contrast with the George Armstrong Custer of progressivism, Bernie Sanders, who is disdainful of compromise and prone to self-righteousness. Despite Warren's well-earned image as a fiery progressive, there is much evidence that her claim to be a unifier is grounded in who she is. She did not summon the CFPB into existence without the gifts of compromise, patience, and a willingness to listen.

But for all her savvy and hard work, is it too late, the campaign too far along, voter sentiment about her too congealed? One appreciates why she stuck with single-payer for so long—and that doing so may have already done her in.

Certainly, that pivotal decision has exacerbated other difficulties which may now cement her ceiling. One is a relative absence of African-American support: while she is working hard to relate her policies to the black community, and is enjoying some success among black women, she still trails Biden and even Sanders. No Democrat can win nomination—or a general election—without overwhelming and enthusiastic black support.

Her spat with at the last debate Sanders—arising from his supposed comment that a woman could not win in November—has undercut her claim to be a unifier. Either Warren is lying, or Sanders is, at best, dissembling. While this contretemps serves neither candidate, Warren could least afford it.

This raises the more amorphous and insidious question of sexism. Warren has begun to argue that her gender makes her more, not less, electable. There is some evidence for this: In 2018 Democratic women won a record number of House seats, and their formidable leader, Nancy Pelosi, epitomizes leadership which fuses intelligence with toughness.

But Kamala Harris and Kirsten Gillibrand emphasized gender and flamed out. The temperate Klobuchar trails the septuagenarian Biden and the neophyte Buttigieg. Female voters, jarred by Clinton's defeat, openly fear a backlash against Warren in 2020. Their fear may well be wrong but, in today’s America, it is not per se irrational.The precincts of gender bias and misogyny may be less visible than kudzu but, once surfaced, all too often they prove no less hardy.

To all this, Warren says: "Back in the 1960s, people asked, 'Could a Catholic win?' Back in 2008, people asked if an African American could win. In both times, the Democratic party stepped up and said yes, got behind their candidate, and we changed America. That is who we are."

One devoutly hopes so. It is repugnant to oppose Warren based on gender and retrograde to do so based on the worry that someone, somewhere, might.

What we know for sure is that, on the eve of primary season, polls show Warren trailing in Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada—and irretrievably buried in South Carolina. They also show a rising Sanders elbowing her aside on the party's left, with progressive icons such as AOC and Michael Moore claiming that Bernie alone can deliver both victory and purity.

Sanders' army of online followers are using Facebook to unleash attacks on Warren so rabid and mendacious that they evoke the most mindless followers of Trump. The prospect of Warren overtaking Sanders on the left seems to have receded by the day..

But, by design, she is extremely well-organized in Iowa, the better to turn out the committed supporters needed to carry a caucus. The coveted endorsement of the Des Moines Register can only help her. She desperately needs a win there or, at least, second place, to buttress her chances in the next two states and, thereafter, to somehow surpass Sanders as a long-term challenger to Biden. But by late Monday her fate may be clearer than she wishes.

If so, it will prefigure an opportunity lost. Not least because, in Warren, a country which needs a new start, bold thinking, and the resolve to reverse our slide toward plutocracy will be losing, perhaps, its best opportunity. She will have been sidelined by an imperative more cosmic than pacifying Bernie Sanders and his blinkered lemmings, more imminent than fighting the maturation of oligarchy: America's consuming need to rid itself of Donald Trump.