Why Are You Still Here?

1. Why?

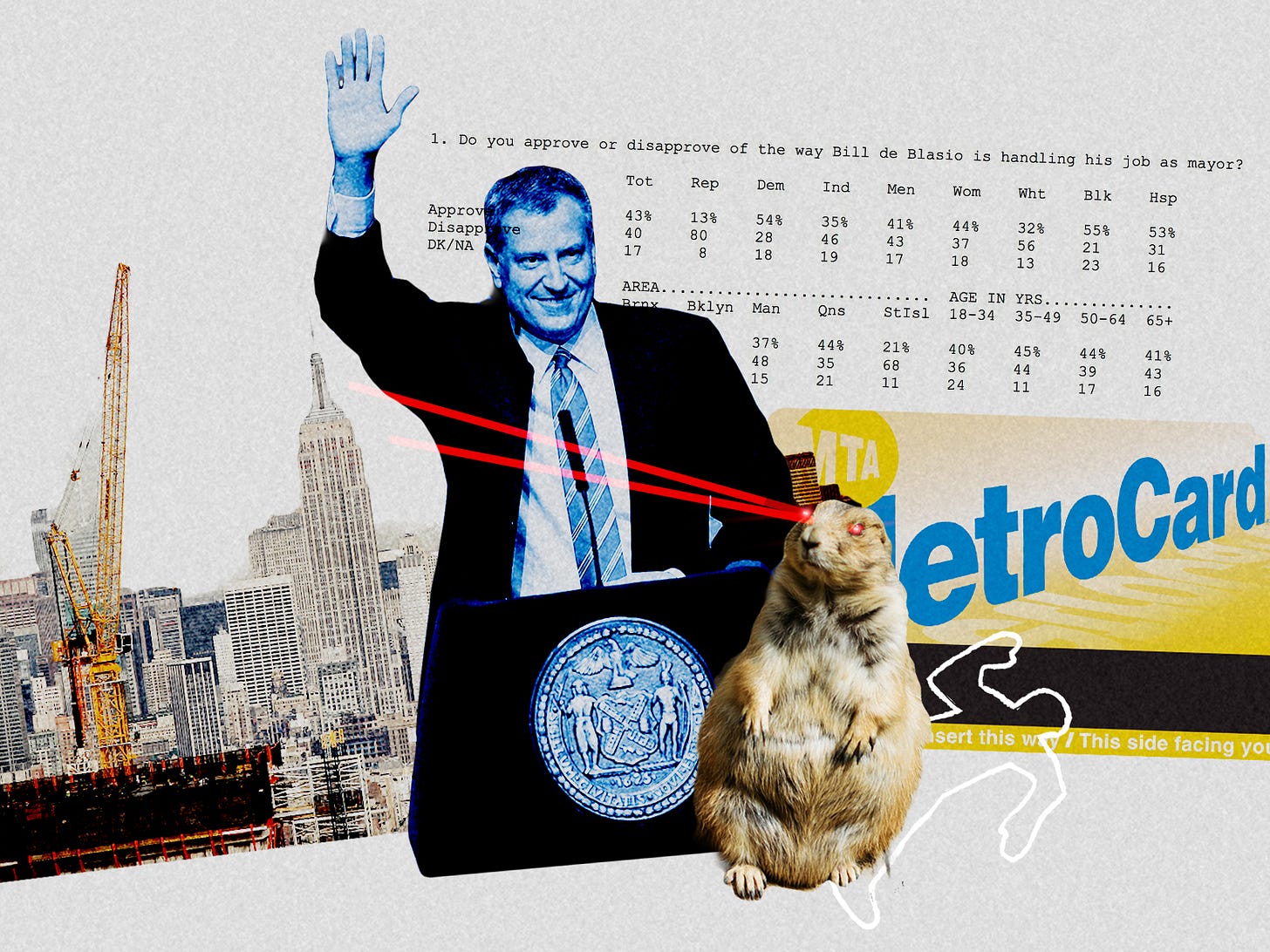

When I look around at the field of people running in the Democratic primary I think about the stinger at the end of Ferris Bueller's Day Off. You're still here? It's over. Go home. Go. Because things like this are now happening: Bill de Blasio is hitting 0 percent in a poll of Democratic primary voters. But that's not the punchline. The punchline is that the poll was taken IN NEW YORK CITY. No wonder he got out. The truth is, I don't blame marginal candidates from getting in and staying in the primary race. They aren't the problem. The problem is the incentives. Traditionally there have been three reasons to run for president: 1) To become president. 2) To get attention for yourself. 3) To champion a cause. And two reasons not to run for president: 1) It's expensive. 2) You can make a fool of yourself. Well, our political culture has rejiggered these items quite a bit. Because over the last few years:

You can get a lot more attention for yourself, even if you never really register in the polls.

The internet has made running a small campaign much less expensive.

There is no longer any such thing as public shame associated with politics.

So basically, we're increased the rewards for unserious candidates and decreased the costs and what you get is Bill de Blasio and Julian Castro and 17-candidate fields, all the way to the horizon. Now maybe you could argue that having a ton of candidates, including a bunch of people who are not seriously running to be president, is somehow good for the process. But I have a hard time with that idea. Because it seems much more likely that having so many irrelevancies in the race makes it more likely for a fluke victories and increased polarization.

2. Warren

This is a fascinating look behind the curtain of what went down when the Working Families Party endorsed Elizabeth Warren over Bernie Sanders. The basic tick-tock:

The WFP announced that its membership voted for Warren over Sanders by 60-34.

But this result was actually the average of two separate votes.

The one vote was conducted among some thousands of grassroots supporters. The other vote was conducted among 56 party leaders. The WFP seems to have added the percentages for these two votes together and divided by two.

Last cycle the WFP used the same process to arrive at its endorsement (which Sanders won) and they released the results of both the grassroots vote and the party leader vote.

This time around, they are refusing to release the results of the two separate votes.

It's almost like the fix was in! Part of what's been going on in the race so far is that Warren has gotten a free ride with no one bothering to try to tear her down. Eventually, she's going to get hit from both sides. The Bernie bros are going to come for her from the left and the Buttigiegs will come for her from the right. This is one of the (many) reasons I remain deeply bearish on her prospects.

3. Boeing

Buried inside this excellent New Republic piece about the Boeing 737 MAX is this exceptional insight about the nature of industry in a free-market system:

A return to the “problem-solving” culture and managerial structure of yore, he explained over and over again to anyone who would listen, was the only sensible way to generate shareholder value. But when he brought that message on the road, he rarely elicited much more than an eye roll. “I’m not buying it,” was a common response. Occasionally, though, someone in the audience was outright mean, like the Wall Street analyst who cut him off mid-sentence: “Look, I get it. What you’re telling me is that your business is different. That you’re special. Well, listen: Everybody thinks his business is different, because everybody is the same. Nobody. Is. Different.”

And indeed, that would appear to be the real moral of this story: Airplane manufacturing is no different from mortgage lending or insulin distribution or make-believe blood analyzing software—another cash cow for the one percent, bound inexorably for the slaughterhouse. In the now infamous debacle of the Boeing 737 MAX, the company produced a plane outfitted with a half-assed bit of software programmed to override all pilot input and nosedive when a little vane on the side of the fuselage told it the nose was pitching up. The vane was also not terribly reliable, possibly due to assembly line lapses reported by a whistle-blower, and when the plane processed the bad data it received, it promptly dove into the sea. . . . No one at Boeing really knew what had hit them after the McDonnell merger. Stan Sorscher was at a family reunion when he started putting the pieces together. He’d been talking (OK, ranting) to his Uncle Sidney, a gentle and brilliant man widely considered to possess the brightest mind to have ever emerged out of Flint, Michigan, about the depraved new managerial culture that had taken hold of his company, when Uncle Sidney cut him off, looked him straight in the eye, and, with a kind of precision and clarity Sorscher had only ever seen in “like, Nobel Prize-winning physicists,” told his nephew:

You are in a mature industry that is no longer innovative; it’s a commodity business. The last great innovation capable of driving major growth in aviation was the jet engine back in the 1950s, and every technological advance since has been incremental. And so the emphasis of the business is going to switch away from engineering and toward supply-chain management. Because every mature company has to isolate which parts of its business add value, and delegate the more commoditylike things to the supply chain. The more you look to the market for pricing signals, the more the role of the engineer will shrink.