Jeff Sessions Tries to Thread the Trumpist Needle

The Alabama Senate race highlights the contradictions at the heart of today’s pro-Trump GOP.

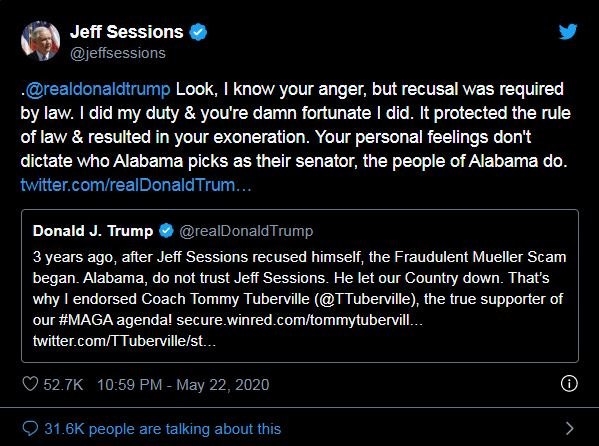

On the evening of May 22, President Trump took to Twitter and resumed his long-simmering feud with Jeff Sessions, his former attorney general and now a candidate in Alabama to reclaim his old seat in the United States Senate. Trump picked up on a theme that Tommy Tuberville, Sessions’s Republican primary opponent who holds Trump’s endorsement, has been hammering for months—that Sessions abandoned and betrayed Trump:

Later that night, Sessions responded:

On and on it went over what should have been a poignant, or at least restful, Memorial Day weekend, with Trump declaring Sessions persona non grata in his world, and Sessions desperate to thread the needle of being his own man while also remaining faithful to the Trumpist project.

It has been assumed by practically every pundit that Alabama is a safe seat for Republicans heading into November. Democrat Doug Jones is on the ballot for a full term after having won the seat Sessions vacated when he was appointed attorney general in early 2017. Jones’s victory in the 2017 special election was always a bit of an outlier; he was and remains a well-respected member of the Birmingham community, and while a liberal in his politics, in tone he is a moderate, if not downright boring. Jones had the perfect opponent in Roy Moore, a social-conservative caricature who was revealed in the late stages of the campaign to have allegedly once had a proclivity for, shall we say, attempting to date much younger women. Once all of this was taken into account, many Republican voters were happy to stay home, vote for a third-party candidate, or even cross the aisle and cast a vote for Doug Jones.

The conventional wisdom holds that Jones won’t be so lucky in a presidential election year. All the usual qualifications abound: Alabama is a red state where President Trump remains popular; Jones voted against the confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh; Jones’s opponent will be either Sessions, who has experience and near-universal name recognition in the state, or Tuberville, a former college football coach who remains relatively popular with voters (or at least those who cheer for Auburn). Facing such odds, Jones is thought to be headed home to Birmingham after November.

I’m not so sure.

While Jones won’t be facing a tiny-gun-toting clown like Roy Moore, each of his potential opponents has a myriad of flaws. Sessions is weighed down by all his Trump-related baggage, while Tuberville is a political newcomer who has never held political office—nor, it seems, a coherent political thought (e.g., he opposes cuts to Medicaid or Social Security because “you pay that through your paycheck”). Blessed with such competition, it stands to reason that Jones has a puncher’s chance to retain his seat.

Let’s look at each of the two GOP contenders in turn.

Jeff Sessions is the most-known political commodity in the race, having first been elected to the Senate in 1996. While Sessions was re-elected three times, it’s uncertain how much of his electoral success was due to his Buchananite policy agenda and how much to the power of incumbency. If there was one issue that tied voters to Sessions it was immigration—the same issue that prompted him to stand out as one of the earliest endorsers of Trump’s campaign in 2016, which earned him Trump’s nod for the position of attorney general. Yet when Sessions recused himself from the investigation of Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election, which in turn led to the appointment of Robert Mueller as special counsel, voters broke with Sessions.

Earlier this year, when Sessions jumped into the race for his old seat, he seemed to believe that voters would be eager to send him back to Washington. He certainly took up enough oxygen to force some other candidates out of the race; by Super Tuesday, the only serious contenders remaining were Sessions, Tuberville, and Congressman Bradley Byrne, a sharp House member who rode into office during a 2013 special election with Tea Party support but whose efforts to out-Trump the field ultimately failed and may have doomed his political career. Sessions outpaced Byrne by several thousand votes but lagged behind Tuberville in the primary vote, leading to a runoff scheduled for July 14.

Sessions’s opponent, Tommy Tuberville, is an interesting case; a man with no prior political experience or consistent policy positions, he publicly mulled a number of second-career options before declaring for the Senate. Thanks to his nearly decade-long tenure as head coach of one of the state’s two football powerhouses (along with amicable relations in the years since his departure from Auburn to coach elsewhere), Tuberville has been able to win the support of state leaders who themselves came to power long after Sessions became a power broker in Washington, D.C.

The interplay between Tuberville and Sessions is like a microcosm of the Trump-Sessions clash—and it highlights the contradictions at the heart of today’s pro-Trump GOP, where personal fealty carries more weight than any policy or ideological persuasion. Sessions did not merely accommodate himself to the new Trump reality; he was an early proponent who saw many of his proposals on trade and immigration embraced by President Trump. His fatal flaw was his own integrity, as he has repeated over and over again that it would have been improper, if not illegal, not to recuse himself from the Russia investigation—and, besides, as he never tires of repeating, he did it to protect President Trump.

Tuberville attacked Sessions for abandoning Donald Trump in his great hour of need, a message that seems to have resonated with pro-Trump diehards. No matter how much Sessions may have helped both Trump’s candidacy and his early months in office, his failure to protect the president from Mueller has proven to be an unpardonable sin.

Meanwhile, Tuberville has left himself open to a Trumpist attack from Sessions in the area of trade; the former coach is far more sympathetic to free trade—and, consequently, relations with China—than either Sessions or the president he is so eager to serve.

The disconnect between a candidate professing obsequious pro-Trump loyalty while arguing for a trade policy that runs counter to Trump’s preferences may be explained by looking at Tuberville’s core support. Tuberville holds endorsements from many figures in the state’s business community, particularly the farming and timber industries, both of which have been harmed by the president’s trade war. In Tuberville, business-minded Republicans have a candidate who would pursue policies far more beneficial to their own well-being, as evidenced by the Club for Growth’s endorsement. Much as members of the Republican establishment supported Donald Trump in hopes that they might restrain him to their own benefit, many state leaders believe that Tuberville could likewise be an avatar for their own interests.

Yet there remains the problem that Tuberville is an ambitious man with no prior public commitment to any of the policies or values associated with conservatism in the pre-Trump era. One might assume that a longtime SEC football coach would have somewhat of a culturally conservative disposition, but that tells us nothing about what Tuberville actually believes about trade, health care, or even the basic legislative process.

Should Tuberville win the primary and then in the general election flip the seat back to the GOP, it’s a safe bet that he will fill three roles in the Senate. First, he will represent the interests of the state’s business community in much the same manner as any other politician. Second, he will be a reliable vote for whatever Mitch McConnell wants or needs. Third, Tuberville is likely to remain a vocal Trump supporter—should the president be re-elected. Under a President Biden, a Senator Tuberville would be a witty, opinionated voice of opposition, but it seems unlikely that he would be part of any shift toward responsible Republican governance in the post-Trump era.

Tuberville’s rise has something of the scent of smoke-filled back rooms. Without the support of numerous leaders in the state’s agricultural sector, it’s likely that the former coach would have disappeared as a vanity candidate months ago. Yet some institutional guardrails might have existed to prevent a candidate bereft of policy ideas from winning a seat in the world’s greatest deliberative body. In the absence of a powerful party, leaders fall back on their own tribal self-interest, but in doing so they undermine the preconditions for any institutional renaissance that would lead to a more stable, less populist government. Then again, less populism might not be to their advantage.

All of which brings us back to Doug Jones. Make no mistake: Jones is a liberal in every conventional sense; he is not an economic or foreign policy progressive. Consequently, if suburban and college-educated voters are faced with the option of an inexperienced, unpredictable Tommy Tuberville whose loyalty is to his financial backers and an erratic president or six more years of moderately liberal Doug Jones, they may just opt for the devil they know.

This is how parties collapse; when they lack the institutional strength to protect their own purpose and reputation—their own ideas—there is the corresponding risk that despite all reasonable arguments to the contrary, voters will abandon them. Every election that Republicans spend arguing over loyalty to Donald Trump is an election with the potential for voters to flee to a party that does not make such demands. It happened once before in Alabama. There is no reason to think it cannot happen again.