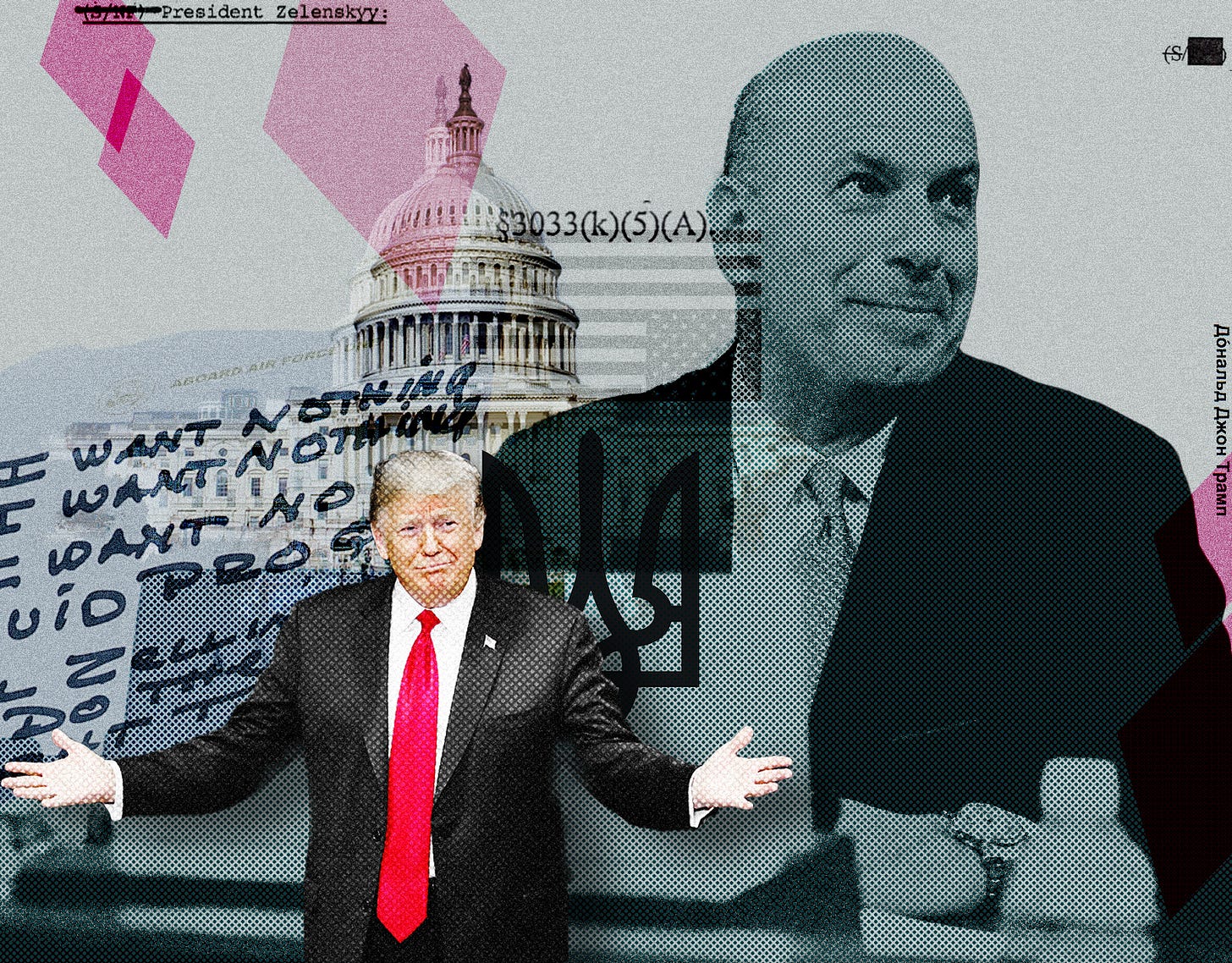

Sondland and Trump Deserve Each Other

This week America saw the difference between political hacks and policy professionals.

There have been seven high-profile witnesses so far during the impeachment hearings: Ambassadors Marie Yovanovitch, Kurt Volker, and Bill Taylor, Mr. George Kent, Colonel Alexander Vindman, and Dr. Fiona Hill.

And Ambassador Gordon Sondland.

The first six were class-act witnesses. They were respectful and charismatic. They knew their business. They answered the questions as they were asked.

Then there was Sondland.

During the closed-door hearing, Sondland said that there was no quid pro quo concerning aid to Ukraine and Trump’s required investigation of the Bidens. But after the fact, Sondland revised his testimony and said there was, in fact, a quid pro quo. And then came the open hearing, during which Sondland absolutely flipped on Trump and became virtually a hostile witness against the president, revealing that the White House had not cooperated with his own lawyers.

None of this should surprise us. Here’s why:

The first six witnesses I mentioned are career professionals. They have spent decades studying and practicing public policy. In Vindman’s case, he has risked his life in the service of country. In the Trump era, they stuck to the policy scene they grew up in and refused to join the circus when Bannon and Jivanka and the Gorka came to town.

Not Sondland. Sondland is a creature of Trump’s swamp. He’s a hotelier whose sole qualification for becoming ambassador to the European Union is that four of shell companies he controlled donated a total of $1 million to Trump’s inauguration.

Here is everything you need to know about Sondland:

After Trump captured the Republican nomination in 2016, Sondland was publicly committed to hosting a fundraiser for him. But then, after one scandal or another, Sondland cancelled the event, saying through a spokesman, “Trump’s constantly evolving positions diverge from their personal beliefs and values on so many levels” and that the Sondland and his wife could no longer support him.

But then Trump won. And so Sondland sought to get back into his good graces by funneling $1 million into the fund for Trump’s inauguration through the shell companies. Because he didn’t want to put his name on the money himself.

It was a good investment. In 2018, Trump nominated Sondland to be ambassador to the European Union. The Republican Senate confirmed him because, evidently, $1 million is the going rate for a strategically important ambassadorship.

It is regrettable, but not uncommon, for donors to be rewarded with ambassadorial posts. But usually these postings are to countries who are not strategicallyhigh priority to America’s interests. It is highly unusual for a position such as ambassador to the E.U. to be used as a patronage job.

There are two reasons for this. First, these positions require expertise and the potential political costs to the president of having an incompetent actor embarrassing him in one of these positions outweighs mere money.

Second, precisely because presidents typically try to avoid the kind of thrill-seekers who want to use their money, not just to buy status, but to try to elbow their way into real-deal, high-stakes geopolitics. Guys like that practically have “born to lose” tattooed across their foreheads. A wise president avoids them like the plague.

Washington has always been more Veep than House of Cards. But despite that, the city’s policy professionals are, by and large, decent persons of professional integrity. When there is stabbing, they stab each other in the front. They come to Washington to do good and serve the country. Not all of them, of course. They are flesh and blood. But on the whole, whatever you think about the nature of bureaucracy or the policy preferences of administrators and career civil servants, we are a blessed nation for their character and professionalism.

The Sondlands of the world, on the other hand, are a good bit more mercenary. They donate to the person they think is most likely to become the party's nominee. For Sondland, that was Mitt Romney in 2012 and Jeb Bush in 2016. (Full disclosure: I volunteered for Jeb Bush in 2016.) Sondland eventually got aboard the Trump train but then, when it looked like Trump was a sure loser, he hopped off.

And when Trump won, he got right back on.

If there is any virtue in Sondland’s testimony, it’s that, as a rich guy only looking out for number one, he was unwilling to take the fall for Trump. Neither a true believer nor a normal mortal with finite resources, Sondland was the type of guy who was always going to find an exit.

That Trump wasn’t able to understand that about him is part and parcel with Trump’s inability to understand why a guy like Sondland shouldn’t be be given an important post in the first place.

Under any normal administration, Sondland would have been given an ambassadorship to Palau or Mauritius and Seychelles. Maybe Spain or Portugal, if he were personally close with the president. For only a million dollars, it’s just as likely that he would have been shunted off to serve on some commission as his reward.

But Trump has no idea how politics works. He sees politics as a sum of business transactions. You donate to his campaign, you receive a position. The more you donate, the better the position. When a man like Trump is dictating the terms of the game, then only other Trumpian figures can thrive.

And there is nothing more profoundly Trumpian than self-service without honor.

Trump and Sondland deserve one another.