The Coming Re-Employment Crisis

Congress and the Biden administration need a re-employment strategy that puts workers first.

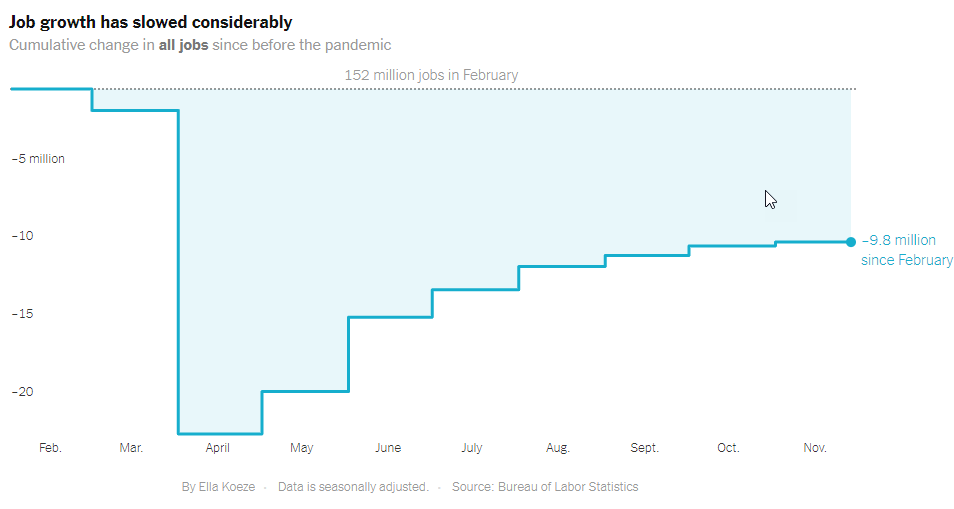

With the United States adding just 245,000 jobs in November—part of a dramatic slowdown in job growth over the past few months—the latest jobs report serves as a warning for what lies ahead in 2021 unless Congress provides additional fiscal stimulus. It also points to renewed urgency for reforming the way the public workforce system supports workers who are caught between COVID-19 and long-term but rapidly accelerating changes in the job market.

Of the roughly 22 million jobs lost between February and April, a little more than half (12 million) have been recovered. Recent slowing in job growth and the stresses created by surging coronavirus infections may lead to a second COVID recession and slow, painful climb-back after vaccines do their work. Some analysts suggest it might take as many as four years just to get back to where we were before the pandemic. Moreover, a lot of these layoffs are permanent, making it harder for workers to get back into the job market.

New York Times graph based on data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The jobs that are gone or going away and probably not coming back are largely in the service sector and concentrated among those with some level of in-person customer or client service that make them especially vulnerable to coronavirus restrictions. These include jobs like beauty consultants, valets, stylists, and pet groomers, all of which were flagged in Glassdoor’s 2021 Workplace Trends report as “most ‘at-risk’” for loss in the post-COVID-19 economy. Other at-risk occupations highlighted in the report include administrative and lower-skilled office roles that are now no longer needed or are vulnerable to automation. COVID didn’t necessarily create these challenges but it has accelerated them and the effects are being felt most acutely by minority and low-income Americans. Left unaddressed, they could have significant impact on job opportunities for those already struggling to find a place in the American economy.

This combination of factors—high levels of unemployment and rapid shifts in labor-market demand—will put the weaknesses of the nation’s publicly funded workforce system under klieg lights. As we saw on the front end of the pandemic, the unemployment insurance system dramatically failed to meet the challenge of mass unemployment. Looking ahead, as vaccines are distributed and infections fall, mass re-employment will create similar stresses on American Job Centers (AJCs), the local agencies charged with helping workers find training and work, threatening to inundate them with a multitude of job seekers chasing limited opportunities. To avoid these bottlenecks and to equip workers with the resources they need to restart their work lives, Congress and the Biden administration should move quickly to adopt new strategies that can both relieve pressure on the workforce development system and help workers access the resources they need to acquire new skills.

In July, alongside Mason Bishop and John Hawkins, we published a “roadmap to re-employment” outlining the critical reforms needed to prepare the workforce system for the surge in demand for services. Our proposals focused on providing assistance directly to job seekers in the form of “Personal Reemployment Accounts” that could be used either for training or for supportive services like childcare, transportation, or relocation. To backstop the worker-focused elements, we also recommended providing resources to states to work in partnership with businesses, local governments, and economic-planning agencies to develop strategic regional restart plans. These restart plans would seek to lift entire economies by restoring the strength of key economic sectors.

We also recommended providing support for states to modernize their labor-market information systems to better connect workers to jobs and to better understand real-time supply and demand of skills in a region.

Finally, we recommended lifting restrictions on the so-called “eligible training provider lists” that govern which training programs are eligible to accept federal funding. This would help to expand the number and types of training programs available to meet worker and business demand. These tools, combined with Personal Reemployment Accounts, will empower those who do not need hands-on support from the workforce system to find their way back to work while reducing the burden on AJCs, ultimately freeing up workforce-system dollars to help Americans with more significant barriers to employment.

The bottom line is this: The drastic, COVID-driven changes in the labor market are forcing many people to rethink their careers and consider additional skill training to better align their abilities with market demand. We need a publicly funded workforce system that puts them and their needs at the center of our policies.