The Coronavirus Crisis and the Politics of ‘Owning’

What should we expect from our presidents?

As the Trump administration faces what is perhaps its first crisis not of its own making, now is a good time to remind ourselves of the point of politics. Because whatever it is, it’s not spreading false information on national TV and Twitter.

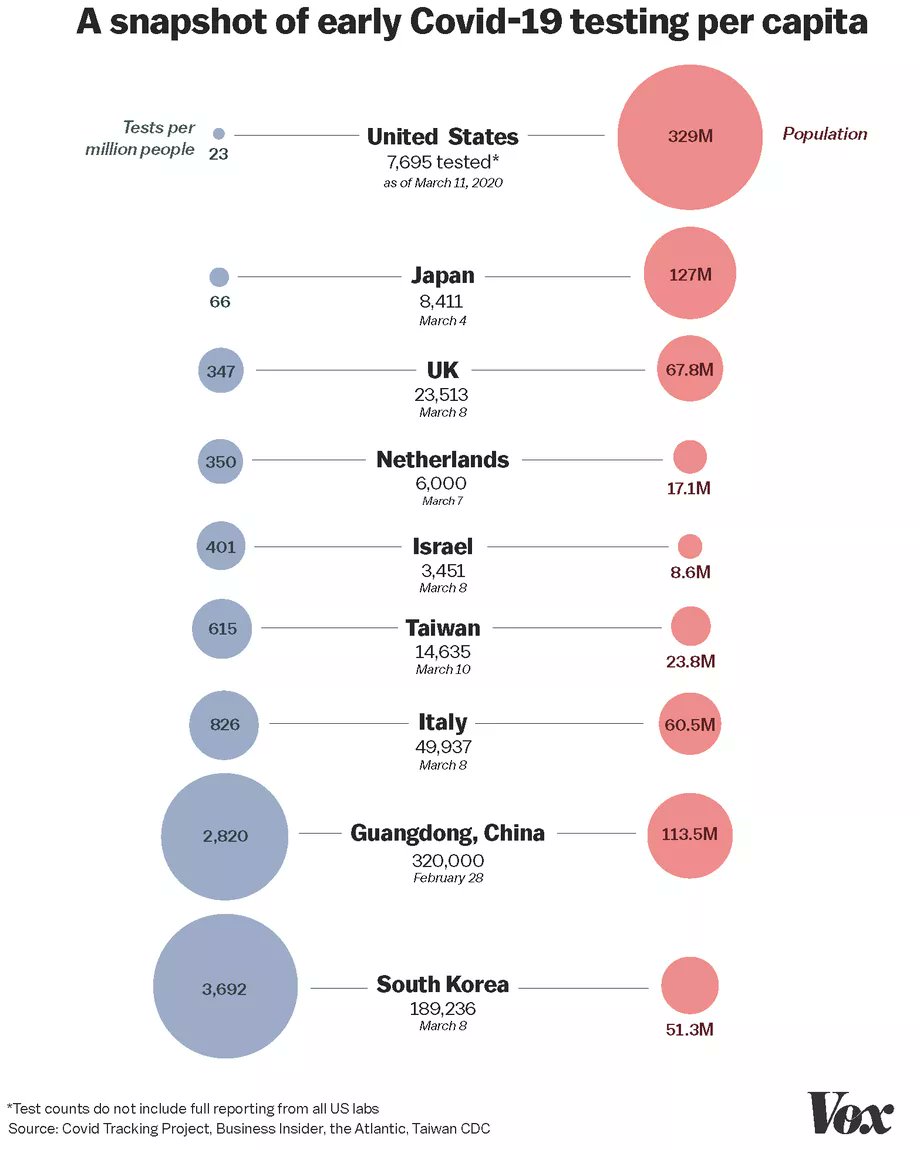

Official counts of COVID-19 diagnoses and deaths in the United States are still relatively small, although the actual number of infections may be much higher, since the United States lags behind every other developed country in testing.

Fortunately, the U.S. testing capacity is expected to rapidly ramp up in the coming days, as explained by various government and private-sector figures at the Friday-afternoon White House press conference.

The press conference may have had the effect of slightly calming some of the public unease about the federal response to the coronavirus. Certainly the stock market reacted favorably, spiking upwards during the press conference after having tumbled steeply during the week. Alongside President Trump, Vice President Pence, and Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar were the CEOs of major healthcare companies and retailers, and Drs. Deborah Birx and Anthony Fauci. Reading from prepared remarks, the president announced plans for dramatically expanding access to coronavirus testing—the first public indication of a comprehensive response to the pandemic.

But most of the reassurance came from the experts present than from the president himself. In one telling moment, when the president was asked if he took responsibility for closing the office within the National Security Council dedicated to pandemic preparedness, he responded, “Well I just think it’s a nasty question . . . . When you say ‘me,’ I didn’t do it,” before trying to use Dr. Fauci as a human shield. “I could perhaps ask Tony about that, because I don’t know anything about it,” the president said, turning away from the microphone and gesturing to Dr. Fauci, who doesn’t work in the White House.

That’s exactly the kind of myopia and immaturity voters were warned about during the last presidential election cycle.

Confronting threats to public safety is just the kind of public good that modern governments exist to provide. We usually think of threats to public safety in terms of foreign attackers or terrorist groups or criminal activity, but the principle also applies to global pandemics. Competent government is capable of interagency policy coordination, wide and rapid dissemination of useful and accurate public information, warning tempered with reassurance, and other things we generally call “leadership.”

Before Friday’s press conference, there was little public evidence that the Trump administration was addressing the crisis responsibly. In fact, the president may have, through his misinformation, made it worse.

Not that this was unexpected. There was no shortage of experts, public servants, and commentators warning before the 2016 election that then-candidate Trump was fundamentally and unalterably unfit to be president of the United States.

Jim Geraghty of National Review last year provided a handy synopsis of why he was elected anyway:

And then one day in 2015, this outlandish celebrity came along who seems to agree with you most of the time. He’s a bit of a jerk, but you kind of like that; he treats everybody who disagrees with him with contempt, the same way the other side treats you with contempt. As time goes by, you realize he’s perhaps more than a bit of a jerk, he’s a raging narcissist and maybe a maniac, but you still like the way he responds to everyone you don’t like—the mainstream media, Democratic politicians—with this constantly erupting volcano of scorn. You feel like you’ve been mistreated for decades; now turnabout is fair play.

Leave aside, for the moment, that tit-for-tat morality makes no sense when the people on the other side are your fellow countrymen whose destiny, whatever it may be, is inextricably bound to yours. And leave aside that indulging in the base, animalistic political passions can be terribly destructive.

Focus instead on the priorities of the hypothetical average Republican that Geraghty describes. It’s nothing new to point out that owning the libs is no substitute for policy achievements. President Trump has solidified support among his base by enraging the right people, even while failing to repeal Obamacare, to build the wall, to have Mexico pay for it, to pay down the debt, to renegotiate the Iran Deal, to balance the federal budget, etc.

But even if the Trump administration had successfully accomplished the whole list of conservative policy reforms, that still wouldn’t mean that Donald Trump is fit for the office of the presidency. Because policy and leadership are different. And—quelle surprise!—President Trump didn’t turn out to be much of a leader.

Ideology and policy preferences are perfectly valid considerations when choosing between two candidates of roughly equal competence. There can be other tie-breakers, too, but making political opponents shriek with frustration shouldn’t be one of them. But the first test should be, as Pete Wehner argued in The Atlantic this week, can this candidate lead the country through a crisis?

The problem with this question is that the future crises are often impossible to foresee—and always impossible to foresee in detail. But there have been enough crises in this young century—election interference, ISIS, the Great Recession, 9/11—that the broad idea of unforeseen emergencies shouldn’t be difficult to conjure.

We should be able to imagine that there’s more to politics than winning and losing, and more even than policy reform. As Charles Krauthammer put it:

Politics, the crooked timber of our communal lives, dominates everything because, in the end, everything—high and low and, most especially, high—lives or dies by politics. You can have the most advanced and efflorescent of cultures. Get your politics wrong, however, and everything stands to be swept away. This is not ancient history. This is Germany in 1933.

In another way, this is America in 2020.