The Rad-Trads Have Decided That, Akshualllllly, George Will Is a Liberal

Apparently he’s a little too tolerant of who gets to occupy the public square.

One of the more frustrating aspects of our discourse being tainted by social media is that, for every viral statement, there are hundreds of responses explaining that, actually, reality is very different. Scientist says something important? AKSHUALLY, that’s not true. Obviously racist comment by the chief executive? AKSHUALLY, what he meant was something completely anodyne, and besides, that’s just how old guys from Queens talk.

We’re all prone to it. A few weeks ago liberal commentators fell into this trap when Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez used the term concentration camp to refer to the detention facilities along the southern border. AOC’s left-wing compadres tripped all over themselves to declare that —actually—concentration camps existed long before Hitler flunked out of art school, and, you know, it was our friends the British who first set up such camps during the Boer War. And, actually, that was true. But as was remarked over and over again, the term “concentration camp” has a cultural resonance that is pretty specific, and even vociferous opponents of the administration had to call bull on all that.

Sometimes history has a way of outdoing the facts. You could use practically any other term for a detention camp, except perhaps gulag, and no one would bat an eye. Instead, AOC decided that the universal term for Nazi death camp was appropriate for admittedly inhumane detention camps, and her defenders threw their backs out carrying water for her.

Conservatives are not immune to this weakness. Take the case of President Trump’s July 4 celebration. Liberals could not resist calling out Trump’s fascination with symbols of military strength that bear more than a passing resemblance to the displays so often found in autocratic nations. To the rescue came conservative with their own example of acutally-itis. Normally Trump-skeptical commentators noted, that, well, tanks are pretty cool. Kids love them! Besides, we’ve had military parades before.

And again, those corrections were not entirely off base. If I had been in the district, the temptation to take my kids to get a look at some military equipment and watch the Blue Angels would have been strong. The problem with this bout of correction is that even Trump’s reluctant defenders are working overtime to ignore his penchant for ostentatious displays of wealth and strength that are unbecoming at best, and undemocratic at worst.

So you see how this works. The actually is often correct in a technical sense. But the correctness often misses the point.

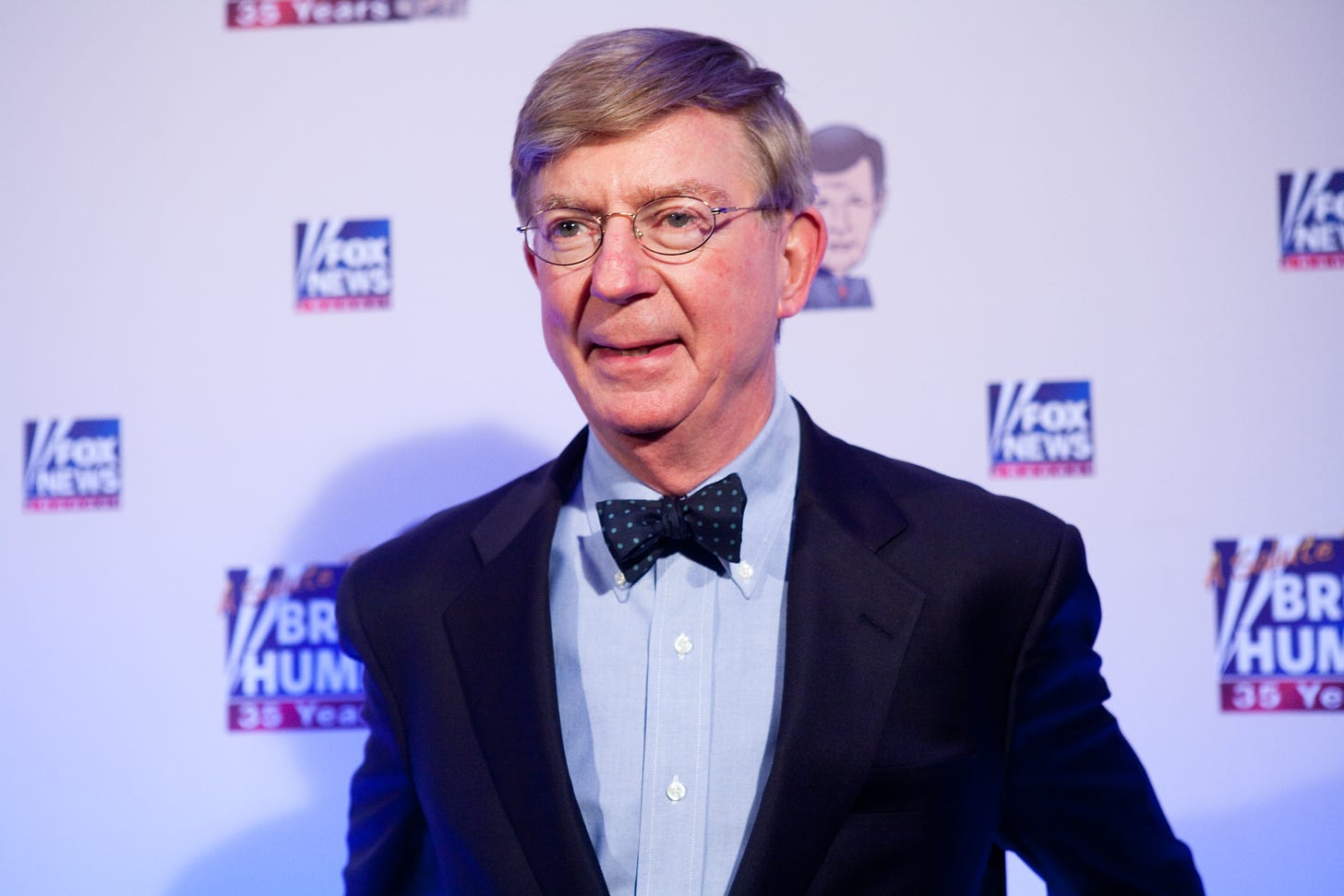

Which brings us to George Will, and the traditionalist objection to his new book, The Conservative Sensibility. The most significant response to date has come from Matthew Schmitz in a First Things piece titled “The True Con.” The title of the piece quickly gives up any good faith as it assumes that Will, a 50-year veteran of conservative punditry, is a con man only pretending to engage with true conservatism. He goes on to bemoan Will’s “complete ideological reversal” and gives Will, a resolute pro-lifer, credit only for “denouncing the systematic killing of infants with Down syndrome.”

Schmitz recognizes Will’s role among American elites as a sort of good, respectable conservative —again, the only True Conservative. But he calls out that lofty role mostly so he can tear him down by arguing that Will’s conservatism is in fact stale liberalism.

Will admits that he has evolved on some issues between the 1980s and today. He no longer argues in favor of “statecraft as soulcraft,” believing that—as citizens are free to pursue their own interests—society will manage to arrange itself into a natural order of one sort or another. This is not enough for Schmitz, who insists that the real true conservatism is the infusion of specific religious morality within the wheels of the state. (Indeed, we’d all be better off if these traditionalists would define what sort of church-state marriage they’re envisioning).

Schmitz doesn’t seem to notice that he’s falling prey to the actually trap. By refusing to acknowledge varying streams of conservative thought, he becomes the very criticism he levels at George Will, the idea of the one True Conservative. He might be correct that Will has changed his views over the years. But that’s missing the point.

I won’t pretend that Schmitz doesn’t have a lot of history on his side when he appeals to giants such as Whitaker Chambers and Russell Kirk. Will boldly argues against the insistence of these men that conservatism must be religious in its nature. For my own part, I’m sympathetic to that line of thinking, but Will has the greater portion of my sympathy because faith - especially the Christian faith - is hard. I am a confessional Protestant, though admittedly a cranky and at times unhappy one. It is not an easy thing to believe in Christianity, what one singer-songwriter once called “the unbelievable Truth.” To write someone out of conservatism because they cannot make the leap of faith necessary to believe the first chapter of John’s Gospel is unfair, if not cruel.

Schmitz errs in his argument with Will because in dismantling Will’s Hayekian framework of America as an ideal and not a place, he creates an edifice of nationalism that treats figures like Marine Le Pen and Victor Orban as like-minded fellow travellers. This “higher good” that has been so passionately espoused by traditional conservatives does not appear to possess a limiting principle that wards off authoritarianism. Yes, it’s true that classical liberalism allows for a wide variety of personal choices in the marketplace, the home, and the spirit, and these choices present a very real challenge to traditional faith. Religious believers are working harder than ever to figure out how to live in a public square that seems in conflict with their suppositions. Will’s libertarian turn is the wiser move, though, because it keeps power out of the hands of a government that may not always hew to a vision of the higher good that meets the standards of the First Things editorial board.

The actually problem is usually a feature of policy or history debates. It is less common in debates over philosophy or theology. When Schmitz declares that, actually, George WiIll is not a true conservative, he ignores most of Will’s substantive arguments in favor of a history lesson. And it’s fine for Schmitz to call upon a certain conservative tradition, but that does not invalidate Will’s decision to call upon a different conservative tradition. In our moment of resurgent nationalism, Will’s refusal to give up on classical liberalism provides a strong limiting principle to impulses that would allow all sorts of bad actors to slip in the back door. Though white nationalists were thankfully excluded from the recent National Conservatism conference, it is getting harder to distinguish good faith arguments from bigoted ones.

Schmitz’s actually problem is that he builds ideological unity on a pre-modern concept of the higher good. In a purely academic sense, that’s fine, but Western liberalism’s strength is its ability to filter out the old prejudices that made the peace of the modern world possible. In reverting to that pre-modern world, Schmitz’s “true conservatives” would resurrect a world of competing, irreconcilable ideological and religious commitments that would make the liberal peace impossible. And whatever the sincere challenges of living in our naked public square, that, actually, would be a tragedy.