Federal Judge Smacks Down Trump’s Executive Privilege Claim

But appeals could keep his White House records relating to the Big Lie out of the hands of the January 6th committee until after the midterms—when it might cease to exist.

In a tightly reasoned ruling issued Tuesday night, U.S. District Court Judge Tanya S. Chutkan rejected Donald Trump’s claims of executive privilege for official records pertaining to his Big Lie, essentially holding that Joe Biden—not Donald Trump—is the president of the United States with the authority to decide whether the public interest favors presidential records going to the U.S. Congress.

The dispute centers on a request by the House committee investigating the January 6th attack on the U.S. Capitol. The committee seeks records maintained by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) pursuant to the Presidential Records Act (PRA). The PRA was one of several post-Watergate reforms. After President Richard Nixon’s August 1974 resignation, he threatened to destroy Oval Office recordings related to the scandal that forced him from office. In late 1974, Congress passed a law forbidding the destruction of Nixon’s—and only Nixon’s—presidential records. Nixon sued, arguing that the law violated the separation of powers; in 1977, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected his argument. The next year, Congress passed the PRA to make clear that such records—from any administration—belong not to a president personally but to the American people, and that no president can legally destroy them.

NARA, the agency charged by the law with managing presidential records, enacted regulations that enable former presidents to object to the disclosure of records, but ultimately lodged the authority to decide on disclosure requests with the incumbent president. Former presidents can seek to restrict access to especially sensitive records for up to twelve years, but the statute also gives Congress access in the interim as “needed for the conduct of its business.”

President Biden exercised his authority to authorize the release of the January 6th-related Trump records and, predictably, Trump sued to stop NARA from disclosing them. He argued that the records are protected by executive privilege, and challenged the constitutional legitimacy of the PRA’s scheme of giving incumbent presidents the power to control that privilege in the public interest. In the alternative, he asked the judge to look at the 800-plus records herself and make the call, essentially transferring the power from Biden to the federal judiciary. She refused to take the bait.

Keep in mind, first and foremost, that nothing whatsoever anywhere in the actual Constitution gives former presidents any power. Once out of office, they become regular citizens like the rest of us. Nor, for that matter, does the Constitution even establish executive privilege. It’s a historical and court-made doctrine designed to ensure that presidents feel safe discussing matters with close advisers without fearing public disclosure and political fallout. If presidents could not discuss matters of national importance in confidence, they might not discuss them at all, which would be bad for presidential decision-making and thus bad for the American people.

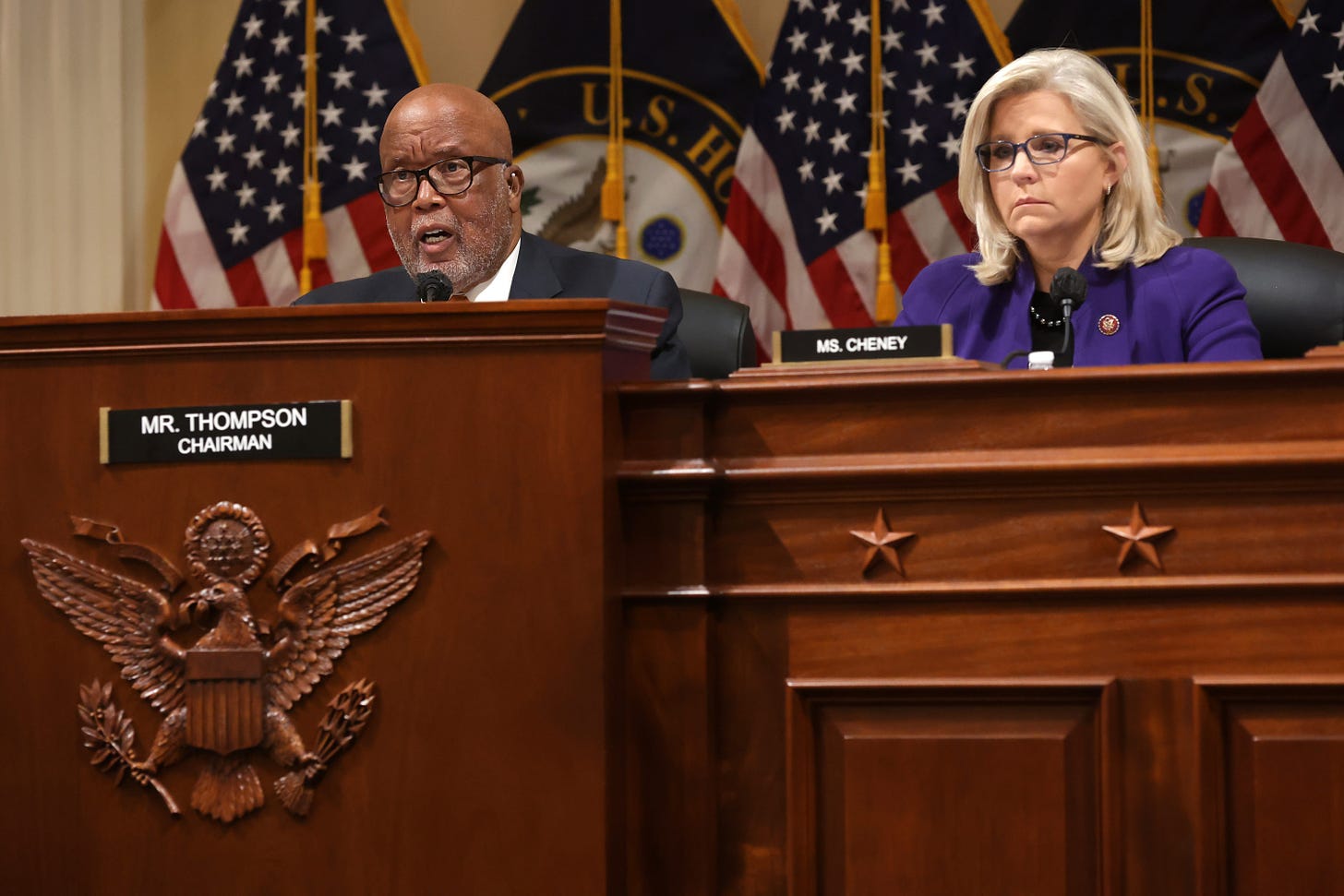

Judge Chutkan acknowledged Trump’s concerns and the legal reality “that executive privilege may extend beyond a President’s tenure,” but agreed with Rep. Bennie G. Thompson—the chair of the Select Committee and a defendant in the case—that “the privilege exists to protect the executive branch, not an individual.” Hence, “the incumbent President—not a former President—is best positioned to evaluate the long-term interests of the executive branch and to balance the benefits of disclosure against any effect on the . . . ability of future executive branch advisors to provide full and frank advice.”

The judge went on to lay out the valid things that Congress could do with the information Trump objects to disclosing, including:

“enacting or amending criminal laws to deter and punish violent conduct targeted at the institutions of democracy”;

“enacting measures for future executive enforcement of Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment against any Member of Congress or Officer of the United States who engaged in ‘insurrection or rebellion,’ or gave ‘aid or comfort to the enemies thereof’” (the provision prohibits such people from serving in the government);

“imposing structural reforms on executive branch agencies to prevent their abuse for antidemocratic ends”;

“amending the Electoral Count Act,” the law that enables members of Congress to attempt to thwart the will of the people by baselessly objecting to Electoral College certifications from certain states;

“and reallocating resources and modifying processes for intelligence sharing by federal agencies charged with detecting, and interdicting, foreign and domestic threats to the security and integrity of our electoral processes.”

Although the judge listed these examples as evidence of legitimate purposes for which Congress might use Trump’s records, they almost read like a wish list of reforms—the kind of things that a more functional Congress managed post-Watergate. Alas, it sounds these days like a fantasy. In this moment, democracy would be served merely by reminding the American people through disclosure of the facts surrounding January 6 that we almost lost government by “We the People” that day—and that the peril of a repeat performance, or worse, remains very real.

Trump, as always, is hedging his bets that delay and obfuscation will work for him. His team has already signaled an intent to appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Assuming that court rules by early 2022, the case could go to the U.S. Supreme Court, which would be positioned once again to exercise its seemingly whimsical power to hear certain cases on an “expedited” basis. The goal of Rep. Thompson’s team is that Democrats in Congress get the information before the midterms, which will occur exactly one year from yesterday.

If the Court decides to hear the case on a regular schedule and, as many predict, Republicans take over the House come November 2022, the Select Committee’s work will cease. That would be a travesty of epic proportions. As Judge Chutkan concludes: “The public interest lies in permitting—not enjoining—the combined will of the legislative and executive branches to study the events that led to and occurred on January 6, and to consider legislation to prevent such events from ever occurring again.” “Presidents are not kings,” she notes, “and Plaintiff is not President.”