History Offers the GOP a Path Away From Trump

Decades have passed since a party opponent challenged an incumbent president; it’s been even longer since one succeeded. This time could be different.

A Washington Post-ABC News poll out Tuesday showed strong opposition to a second Trump term. The bottom line should worry even overconfident stalwarts of the president: 56 percent of those asked about their 2020 choice declared they would “definitely not vote for him,” a figure consistent with other recent polls.

But another potential hell-broth boils for Team Trump. The poll shows that nearly one-third of Republican and GOP-leaning independent respondents said they want the party to nominate someone other than Trump in 2020.

Conventional wisdom has held that Trump is too entrenched, too emboldened, too blindly followed by cultish supporters to face a strong primary challenge. These poll numbers suggest otherwise. More importantly, so does history.

Beyond the memory of most living Americans lies a time when the major parties rejected their own incumbents to avoid just the kind of electoral drubbing that these new polling numbers portend for Trump.

Without a doubt, a party’s choice to ditch a sitting president (or, better yet, to get him to step aside and thus avoid an embarrassing vote at the convention) brings significant pain. But past generations of partisans have calculated that booting a toxic incumbent bodes better for their interests than waiting for the voters to remove him. In fact, history shows a party can keep the White House without the burden of defending an unpopular and unwelcome president.

It didn’t happen during the first half century or so of American politics. George Washington, who led no party, set a precedent by stepping away from re-election after two terms. His successors followed suit, keeping the support of their parties until they either left office (Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson), lost the next election (both Adamses and Martin Van Buren), or met the grim reaper (William Harrison).

The 10th president, if only in this one respect, was a trendsetter: John Tyler in 1844 began a six-president cascade of men who failed to appear on their party’s ballot in the general election following their first term. One, Zachary Taylor, literally had no choice; like Harrison, he died in office. For the others, national agonizing over slavery and other tensions within each of the major parties made it difficult for any president to sustain a governing coalition. Only James Polk left with a solid reputation and a ledger of successes.

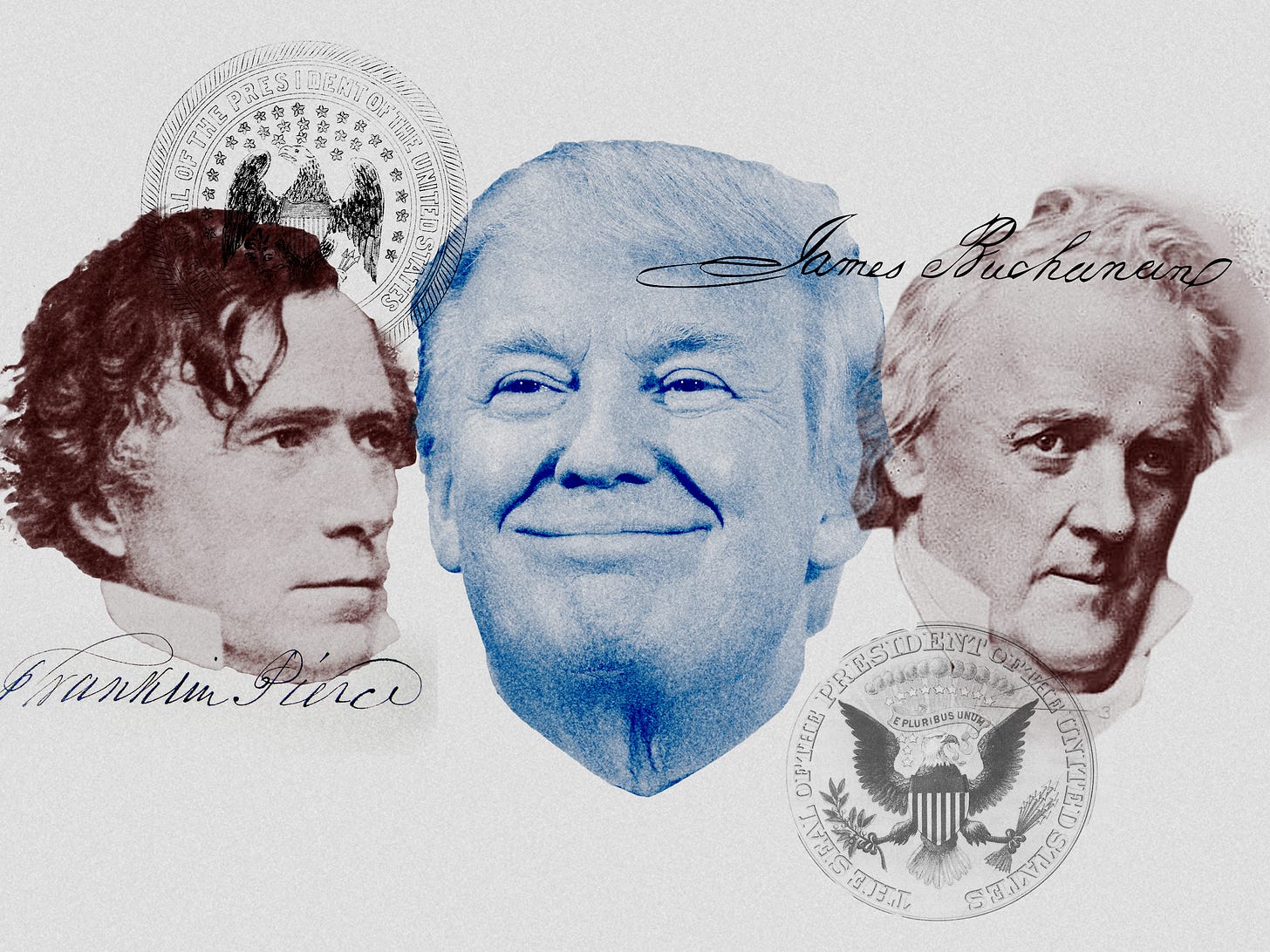

The three presidents who followed Polk—the forgettable series of Millard Fillmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan—share three characteristics. First, historians routinely rank them among the nation’s absolute worst. Second, and related to that, they took no responsibility for resolving the national moral failure of slavery. And third, no matter how they had attained office, they found themselves spurned by their own parties.

The case of Pierce in the 1850s is particularly instructive for potential Republican challengers to Trump today. On one side of the Democratic party, Senator Stephen Douglas stayed out of the administration and undercut the president’s bid for renomination by quietly building support among pro-slavery Democrats in the South and West. Pierce’s other rival, former secretary of state James Buchanan, served as ambassador in London and used his absence from the United States to duck any blame for the administration’s disastrous legislation (notably, the Kansas-Nebraska Act) and lift his own candidacy. Ultimately, that distance from the unpopular president helped Buchanan win the floor fight at the convention—and the presidency in the general election.

The former president whom Trump most resembles, Andrew Johnson, hoped that old Democratic colleagues would reward him with their ticket’s top spot in 1868 for the pain he had caused to Republicans after Abraham Lincoln’s death. His optimism was misplaced. The party convention instead chose Horatio Seymour, a man who didn’t even want the nomination.

By the 20th century, parties stopped gutting their own. For more than 100 years, few sitting presidents faced significant obstacles to renomination from within their own parties. Even those who did, like William Taft and George H.W. Bush, beat back their challengers to lead their tickets again. (Of course, both lost, and they did so to opponents who garnered less than 43 percent of the popular vote.)

Why focus on the 1840s through the 1880s instead of the 1940s through the 2000s?

To start, Republican contenders may actually learn more from the history books than from recent experience. The rejected incumbents of the mid-19th century operated in an era of fluctuating party affiliations. Today’s parties face similar turbulence in what may be an epochal political realignment.

If so, the polls that show support of two-thirds or more of Republicans for Trump reflect a bit of a statistical artifact. The Trumpification of the GOP has spurred prominent Republicans to leave—and many others to stop publicly identifying with the party. The Washington Post-ABC News poll, for example, shows 32 percent of respondents identifying as Democrats—while only 24 percent self-identify as Republicans. Even within that dwindling core, the president has fractured his own base with his tragicomic back-and-forth tactics to secure funding for his fantastic wall.

Jonathan Last has written here that many potential supporters of moderate Republicans “may have already fled the GOP.” True. But foreseeing a potential matchup between, say, Bernie Sanders and a more traditional, anti-Trump Republican, would not Never Trump donors and voters come back into the fold and participate in the primaries? Many disenchanted Republicans surely would return in primary season to help nominate virtually anyone else in Trump’s place.

Voters and pundits today assume a first-term incumbent president will always receive renomination. That’s natural; it’s all most of us have known. It’s also historically ignorant. In fact, the fire may burn, the cauldron may bubble, and the men who seek power merely for its own sake may again find themselves shoved aside by those who prioritize principles over raw ambition.