A Jane Austen–Style Romance in a Dark Web World

Elaine Castillo finds love in a hopeless place: an office for content moderators.

Moderation

A Novel

by Elaine Castillo

Viking, 320 pp., $29

THERE ARE MANY UNPLEASANT JOBS in this world. But surely one of the worst must be Internet Content Moderator, a job wherein one spends one’s days immersed in the worst our species has to offer while making little pay and helping grow the profits of Silicon Valley gazillionaires. There are certainly physically dirtier and more distressing jobs, such as those that require people to be surrounded by trash or human waste, but the sanitation workers and others in similar roles might be able to remind themselves that their work is necessary, and that most of the shit and garbage they deal with is not a direct product of cruelty; everybody poops, and everybody, no matter how environmentally conscious, must throw things away. But the content moderators who work for social media platforms spend their days immersed in Klan manifestos, child pornography, snuff films, harassment, and unquantifiable amounts of verbal brutality, all so that the rest of us can aimlessly scroll Facebook and TikTok without being inundated by porn, hate, and gore.

This is Girlie Delamundo’s job in Elaine Castillo’s new novel, Moderation, and boy, is Girlie ever good at it. In fact, as the first paragraph tells us:

Girlie was, by every conceivable metric, one of the very best. All the chaff, long ago burned up by unquenchable fire: the ones who had hourly panic attacks, the ones who took up drinking; the ones who fucked in the stairwells during break time, the ones who started bringing handguns to the office, the ones who started believing the Holocaust had never happened, or that 9/11 was an inside job, or that no one had ever been to the moon at all, or that every presidential candidate was picked by a cosmic society of devils who communicated across interplanetary channels; the ones who took the work home, the ones who never came back the same, or never came back at all. The floor was now averaging only three or four suicide attempts a year, down from one or two a month. The ones who remained, like her, were the wheat: the exemplars, tested paladins, the ones who didn’t throw up in the hallway and leave the vomit there. They’d been, to continue speaking of it biblically, separated.

Moderation pulls no punches as to the unceasing horrors of Girlie’s job; she spends her poorly remunerated working hours in a tar pit of pornography and violence, some of which is briefly but graphically described for the reader. But one day, Girlie is introduced to a corporate bigwig who offers her a new, lucrative job: still a content moderator, yes, but now it’s for the company’s prototype immersive VR service.

Also of note: the bigwig, William Cheung, is terribly, terribly attractive.

And nice. And rich, of course.

And, let’s face it: tall.

As Castillo herself has described it, “Moderation is a novel about two people who are extremely sure of themselves—who they are, what genre they think the story of their life is in— and are wrong.” Just how wrong? Well, while one “thinks he is in a corporate espionage revenge thriller about virtual reality and the collusion between the tech industry and the rise of the far right,” the other believes her story is “a hard-boiled immigrant drama about being an anonymous laborer in tech in the post-2008 economic climate.”

But the truth is “they’re both in a Jane Austen–style Regency romance.”

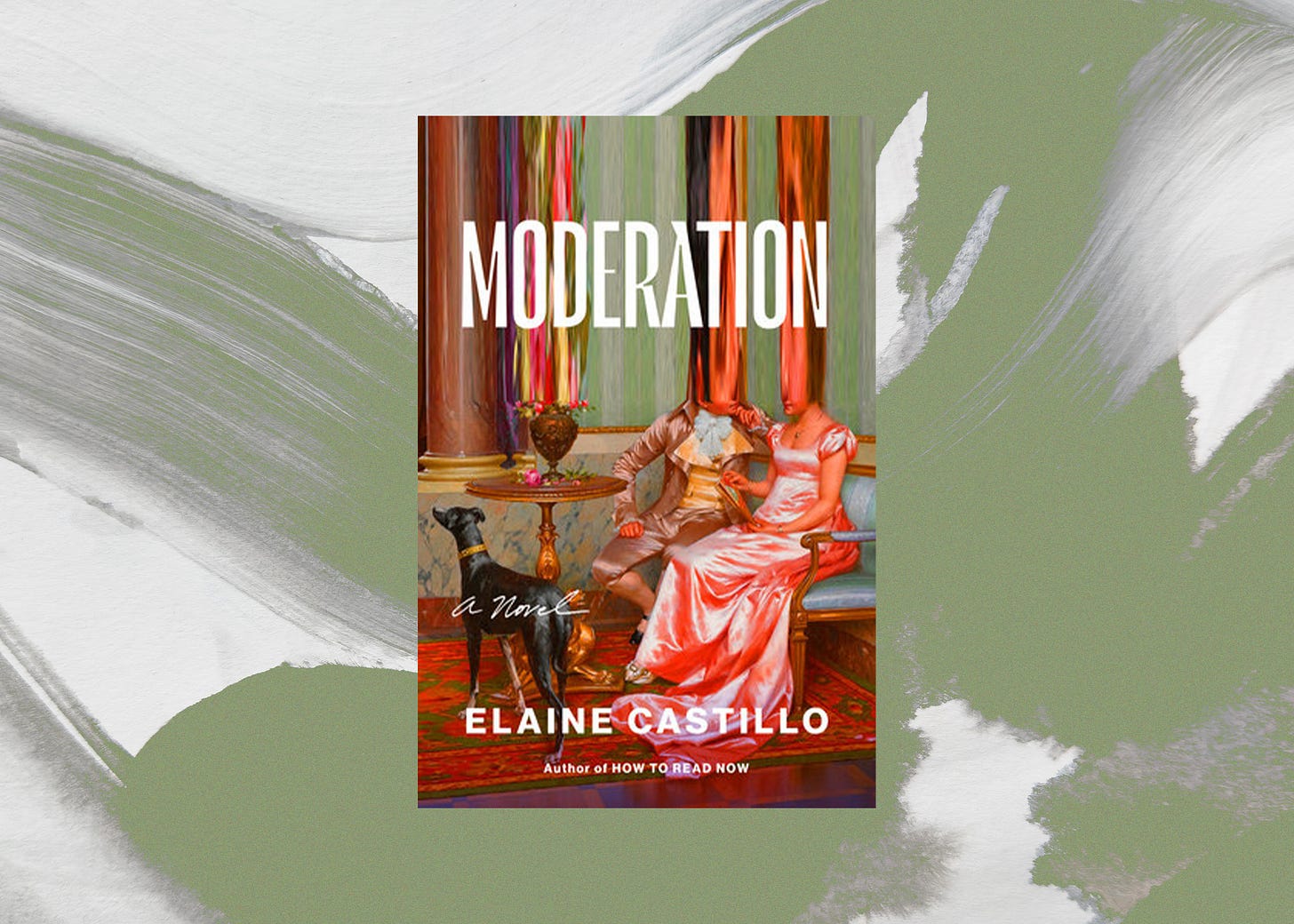

Yes, as Moderation’s cover art implies, this book has more in common with Pride and Prejudice than its first paragraph suggests. It is a satire about the horrors of the internet and modern tech, yes, and it is a story about the immigrant experience, too—but it is also, and most importantly, a love story. It rocks.

IF AT FIRST BLUSH IT SEEMS ODD to attempt to marry an Austen-style romance to a story about the very real divisions and dangers of our society, that is only because we live far enough away from Austen’s world to forget that’s what Austen did, too. Pride and Prejudice is one of the most famous romances of all time, but it is also a wickedly funny satire of the British upper crust and has a keen awareness of the very real ways that entailment laws constrained the lives of even upper-class women, and how vulnerable young women are to unscrupulous men.

Like Lizzy Bennet, Girlie lives alongside a host of family members in a big house they cannot afford. (Prior to the 2008 housing crash, Girlie’s mother bought a large house in Vegas; now she, Girlie, and several other family members all share it, each of them working long hours at unpleasant jobs to keep up the mortgage.) Like Lizzy, Girlie is attractive (a “24-karat hottie,” as the book wryly informs us), witty, well read, and almost wholly uninterested in dating any of the men or women she meets. And like Lizzy, Girlie will fall in love with a man whom her pride and/or prejudice would push her to reject. William is her boss, after all. Won’t someone think of HR?

But lest I give you the wrong impression, Moderation is not a pastiche or parody of an Austen novel. Aside from the fact that its multi-resonant title does sound like one you might expect to see alongside titles like Persuasion and Sense and Sensibility, the novel’s prose is largely free from cheap Austen imitation. (Blessedly, the words “It is a truth universally acknowledged” appear nowhere in the book.) What Castillo does borrow from Austen is the structure of the central story and a sense for how to use a romance plot as a tool to also examine the various broken parts of our society.

Also, Jane Austen never wrote a sentence like “She tried to remember how sophisticated the haptic gloves were, that she could touch sticky caramel popcorn, that she could tear faux fur off a rapist at the Louvre.”

Moderation’s tone is very similar to that of Castillo’s previous novel, 2018’s America Is Not the Heart: wry, honest, cheerfully blunt when describing a character’s sexual desire or frustration with her annoying relatives. It also draws on some of the same subject matter as the earlier book, which centered on three generations of Filipina women living in Milpitas, California and undergoing the trials and tribulations of immigrating to the United States. Girlie grew up in Milpitas, as well, and some of her family background may remind readers of America Is Not the Heart. (From a few biographical details, I actually almost convinced myself that Girlie is one of the characters from the earlier book, but I don’t think everything quite hangs together well enough for that theory to be viable.)

Yet Moderation is not simply another pass through the world of the earlier book; stories about the same community of people will inevitably end up hitting some similar notes. Both books drop words in Tagalog (or Ilocano or Pangasinan), for instance, or make references to common ideas in Filipino culture without explicitly translating them to an unfamiliar audience, but Castillo always provides enough context to make the gist clear. It’s a quiet but important skill: Nothing takes a reader out of a story quite like a narrator who stops every few sentences to provide little Wikipedia summaries of potentially unfamiliar practices and references. This is true whether the culture being written about is a real one or an imagined one.

Tomas, the security guard kuya at the entry to the main floor of the Bellagio casinos, recognized her and tipped his hat. He had insisted she call him kuya, even though she was pretty sure she was older than him, protracted youthfulness being a perk of her mother’s genes. There had to be at least one perk.

“Sup, fam,” he said as she passed. “Have a good night.”

“You too, kuya,” she said. Thus were civilizations maintained.

Castillo does not define the word “kuya,” but she doesn’t need to for the reader to get it. (You probably intuited from this excerpt that “kuya” means “older brother.”) Silly as this little scene is, it highlights many of the things Castillo is doing in this book: the exchange offers a comment on the sort of background that would push a younger man to insist an older woman call him “older brother”; it exemplifies the connections that the Filipino community in Las Vegas has with each other; it encourages us to remember that Girlie is perpetually annoyed at the obligations her mother’s irresponsible financial decisions have laid at her feet; it reminds us that Girlie is a total smokeshow; and it ends with a joke—although, the joke can be read literally: perhaps civilizations are, in fact, maintained by women humoring annoying younger men.

Girlie’s new job also gives Castillo time to have some fun with the new VR technology, which was developed primarily for therapeutic purposes, à la exposure therapy, but is now primarily being used to make odd, RETVRN-coded virtual theme parks. The sections describing how Girlie handles the terrible things that some users try to get up to in the VR space are darkly funny, yet the moments when Girlie gets to use the technology for something more resembling its original purpose are surprisingly beautiful. This is not a science fiction novel, and the intricacies of how and why the VR works as well as it does are not elaborated; the gadgetry is not the point. The point is the contrast between the nearly miraculous technology and the avaricious people who exist (William excluded) at the top of the company’s hierarchy, and it serves the book well. In one sense, VR serves as a replacement for one of the great estates an Austen hero might stand to inherit; the imaginative possibilities it opens up can be beautiful, and it’s important for it to stay in the hands of the right people, lest it be misused.

Moderation skillfully weaves together all its different projects into a seamless whole that is alternatingly bleak and moving. Its occasional reminders of the terrible things human beings do to each other serve to make its love story all the more poignant. Here is a book that is fully aware of the worst our species has to offer; here is a main character who swims through the sewer system of our collective mind every day. Yet if it could be possible for even someone as understandably jaded as Girlie Delamundo to find love and a purpose, maybe the rest of us have some hope of doing the same. And if its ending is perhaps a little rushed, and has a sense of, if not quite deux ex machina, at least of things being entirely too convenient—well, have you read Sense and Sensibility lately?