A Teenage Baudelaire in Chicago

Michael Clune’s debut novel dances on a knife’s edge between the heavenly and the hellish.

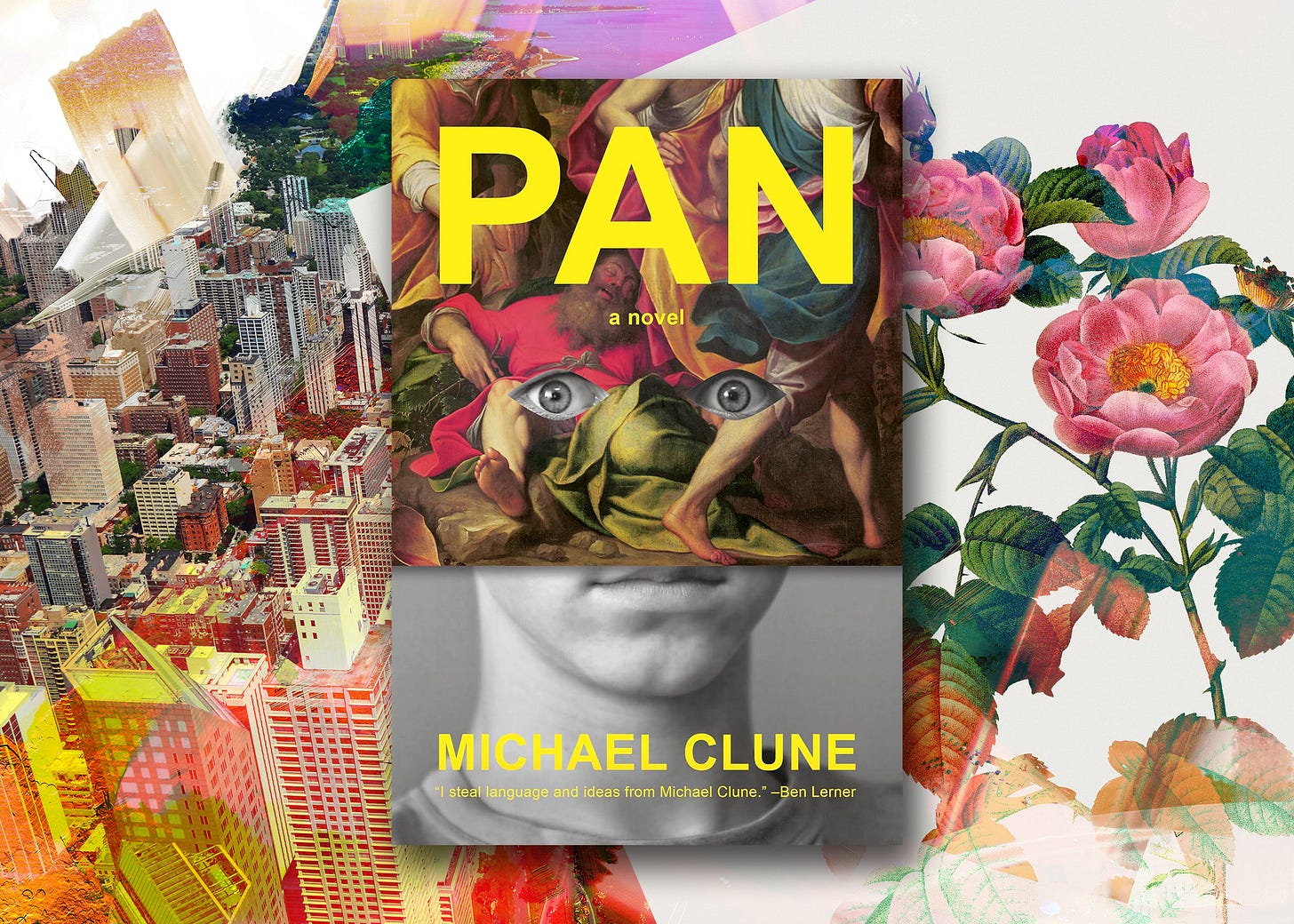

Pan

by Michael Clune

Penguin, 336 pp., $29

“AS A SINCERE CHRISTIAN,” wrote a woman named Caroline Aupick in 1868, “I can’t allow this poem to appear, and certainly if my son were alive today he wouldn’t write such a work, since, in his last years, he showed deep religious conviction and feeling!” Her son, Charles Baudelaire, had died the previous year. Haunted by Catholicism and fascinated by the occult, his poems were profane—and his mother hoped to cull the most blasphemous verse from the third edition of his book, Les Fleurs du Mal.

In an 1857 review of the first edition, one of Baudelaire’s former schoolmates concluded that the poet “voudrait passer pour un méchant diable bien terrible, aux doigts crochus, au pied fourchu”—“wished to pass as a terrible, wicked devil with hooked fingers on cloven hoof.” It didn’t seem too far off; the poet himself once wrote that all men had “two simultaneous and contradictory attractions—one towards God and one towards Satan.”

Although Baudelaire danced with the devil, he did so while holding his cross. In his essay “The Pagan School,” he warned that when artists are “absorbed by the fierce passion for the beautiful, the amusing, the pretty, the picturesque—for these are different degrees—notions of the just and true will disappear.” He cites Saint Augustine’s “remorse” for “the too great pleasure of the eyes.”

He also relates an anecdote from a banquet where an “educated and intelligent” young man raised his glass and toasted the god Pan; he claimed the hoofed deity had started the February Revolution in France. Baudelaire responded sarcastically that Pan was dead, but in an eerie moment that seemed to scare the poet, the man “rais[ed] his eyes to the heavens” and said: “He is going to return.”

PAN, THE DEBUT NOVEL BY MICHAEL CLUNE, arrives on the tail of several well-received books of nonfiction. White Out dramatized his addiction to heroin, and Gamelife documented his pre-teen computer gaming. Both books are frenetic in their own ways, and they are filled with scenes where reconstructed events teem with dialogue. It felt like Clune was well on his way to writing fiction.

For the May 2023 issue of Harper’s magazine, Clune wrote an essay, “The Anatomy of Panic,” depicting his first panic attack, which took place during a geometry class at his Catholic high school in Illinois. But he would soon reframe this product of memory as a product of the imagination: The essay now appears, nearly verbatim and without any indication of its provenance, in the first chapter of his new novel.

None of this is surprising. The exigencies of drafting—and the world of publishing—often influence a writer’s genre. Not all of Pan is “real” in the way the transplanted essay is, certainly, but it feels like all of it is, and that is a compliment to Clune’s ability to meld the real and imagined into a coherent narrative.

Set in Chicago, the novel is focused on a character named Nick. The text begins with a list related to panic attacks. Number 13: “The feeling that I could come out of my body. My head, in particular.” The fragmented list introduces an essential theme of the novel: that during panic attacks, one is acutely aware of one’s body. A moment of strain is, perhaps, the pinnacle of our embodiment. “Panic,” Nick says later, “is the excess of consciousness. Your consciousness gets so strong it actually leaps out of your mind entirely.”

Nick’s parents are divorced. He is living with his dad because his mom kicked him out when he was 15; he was growing personally unstable, and she thought it best for him to be with his father. They live in Chariot Courts, a low-grade development where the bars of their unit’s wrought iron fence “bent into fantasies and curlicues of iron.”

Soon comes the story of his first panic attack—the one Clune himself experienced and wrote about, but which he now imputes to his protagonist. Bodies, in both accounts, are everything. Nick’s geometry teacher “was grotesquely tall” and so thin that he could “demonstrate the angles on his bones.” Nick becomes disassociated from his own body, regarding its parts as so many foreign objects: “My hand, I realize slowly, it’s a . . . thing.” He struggles to focus, and it becomes difficult to breathe.

Not long after, Nick reads Ivanhoe until he finishes it at 4:35 in the morning. Clune then gives us this claustrophobic sequence of simple, direct sentences: “I put down the book. I put on my pants and pulled on my sweater. Then I walked downstairs and told Dad that I was having a heart attack.”

At the hospital, they tell him to breathe into a paper bag if it happens again. His father—focused on concrete solutions and checking off tasks—buys him paper bags on the way back from the hospital. Nick welcomes them as a salve, but when he gets back to school, he is stopped by a nun who admonishes him over a bag he’d stuffed into his pocket: “That’s trash.”

Trash, but useful. The bags calm him, but they aren’t the ultimate fix. Nick’s on edge, despite finding a place of relative social comfort in school thanks to his vaguely badass reputation. He is drawn to a girl named Sarah, and after a scene when he goes to Ruby Tuesday with his friend Ty—unaccompanied by adults, they make a hilariously self-conscious show of their pretentions to maturity—he is pumped and finally calls her.

She invites him over. He’s a bit uncomfortable: “I could tell by the way she moved. This house is a place she looks out from, I thought, it’s not a place she sees.” Despite their economic distance, they grow closer, and she goes with him to the school library during one lunch to look up the word “panic.” (The novel, set before the digital age, makes such actions feel quaint and romantic.) They discover that panic “is derived from the god Pan, and originally referred to the sudden fear aroused by the presence of a god.”

The revelation leads to a pivot in the novel. Pan moves from a coming-of-age story to a portrayal of transfiguration, perhaps even possession. The more Nick hangs out with Sarah and her friends, the more their parties resemble absurd rituals—kids trying to conjure up something more than mischief. Nick feels the change: “I felt as if Pan visible might extend from my eyes—His horns out of my eyes.”

The novel begins to get a bit hazy. The blurring is deliberate; these characters are on drugs, engaging in sometimes earnest, often parodic rituals that strain credulity. Clune never loses the plot, but sometimes Pan comes close. At some points in the story, the line between drugs, play, and possession gets blurred, and Clune seems to revel in the confabulation.

Yet Pan never derails, probably because of Clune’s (and Nick’s) worldview. Late in the novel, Nick shows Sarah a copy of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal. He reads aloud “Twilight: Evening” to her. The lines feel incantatory: “This is the hour to compose yourself my soul; / ignore the noise they make; avert your eyes.”

Like Baudelaire, Nick plays with fire, and often doesn’t mind the burns—provided they eventually heal. The teenager also shares a Catholic sensibility with his literary forebear. Stories that are set in parochial schools often render the institutions stereotypically, as doctrinaire prisons that stymie thought and creativity. But for Nick, Catholicism is his language; it provides a vocabulary for articulating his experiences and giving form to his budding sense of mysticism.

When thinking about Carl, an annoying boy from his school, Nick does so through the prism of theology. Father Snow, his religion class teacher, had recently taught them about the concept of contingent versus essential properties as they relate to Jesus: While Christ’s holiness was essential, his hair color was contingent. The analysis can be extended deep into the mundane: “Carl, I thought, is a contingent property of panic. He just happened to be there during my most recent attack.”

Catholic school kids are just that—kids, and not theologians—but the sensibility they develop is unique, and it sticks with them long past graduation. I tell people that Catholicism is culture, culture, culture, and Pan is one of the best contemporary novels to evoke the paradoxes of the faith. In a lesser novel, Nick’s psychotropic extracurriculars would accompany a season of doubt. He’d lose his religion, realizing that God is dead, Pan is alive, and true freedom lies in escaping tradition. Pan is better than that, and Clune is a complex writer.

In one scene, Ian, the older brother of Nick’s friend Tod, offers him an intellectual balm for his mental stress: a theological schema for understanding it—one that shades into heady numerology. Panic “most often erupts at age fifteen,” Ian explains, for reasons that have been variously articulated throughout Church history:

the human being bursts into the fullness of life. Origen says the number five in the sacred texts refers to the five senses. He says the number three refers to the Mysteries. Fifteen. Five by three. The senses bound by the Mysteries. Cardinal Newman says in his Apology that he first felt his calling at age fifteen. Augustine says he understood the nature of the flesh at age fifteen.

In a secular world, authentic religion has a naturally countercultural aspect. But Pan isn’t a book about piety. It’s a book about divorce, high school, fear, and faith. Imagine a 15-year-old Baudelaire trying to find his way in Chicago.

At the end of Pan, Nick isn’t quite healed of his anxiety—whatever that would mean. After going to one treatment session with a therapist, Nick tells his dad that it helped, but it hasn’t. They leave the office, and as they journey home, we are treated to this sublime paragraph of description:

We drove home through the suburban twilight, not talking. We passed the stunted trees, the thin poles of power lines, the thin poles of traffic lights, the low retail buildings, the little houses, the thin poles of signs. Darkness coming out in the spaces, darkness like a gathering of thin poles, first in the low sky, then on the roadside, then in the car.

Sublimity here shies away from baroque forms. Baudelaire criticized some of his artistic peers for distracting people with ornate but ultimately empty materiality; the French poet thought doing so was tantamount to spreading a spiritual virus among the public. He condemned the way the “plastic,” empty nature of his epoch’s art had “poisoned” the typical appreciator of culture—but, he admits, such a person nowadays “can live only by this poison.” In Pan, Nick is either possessed or inspired by that titular god, the poison dispenser. We may disagree on which thing has happened, but not about whether he has been changed.