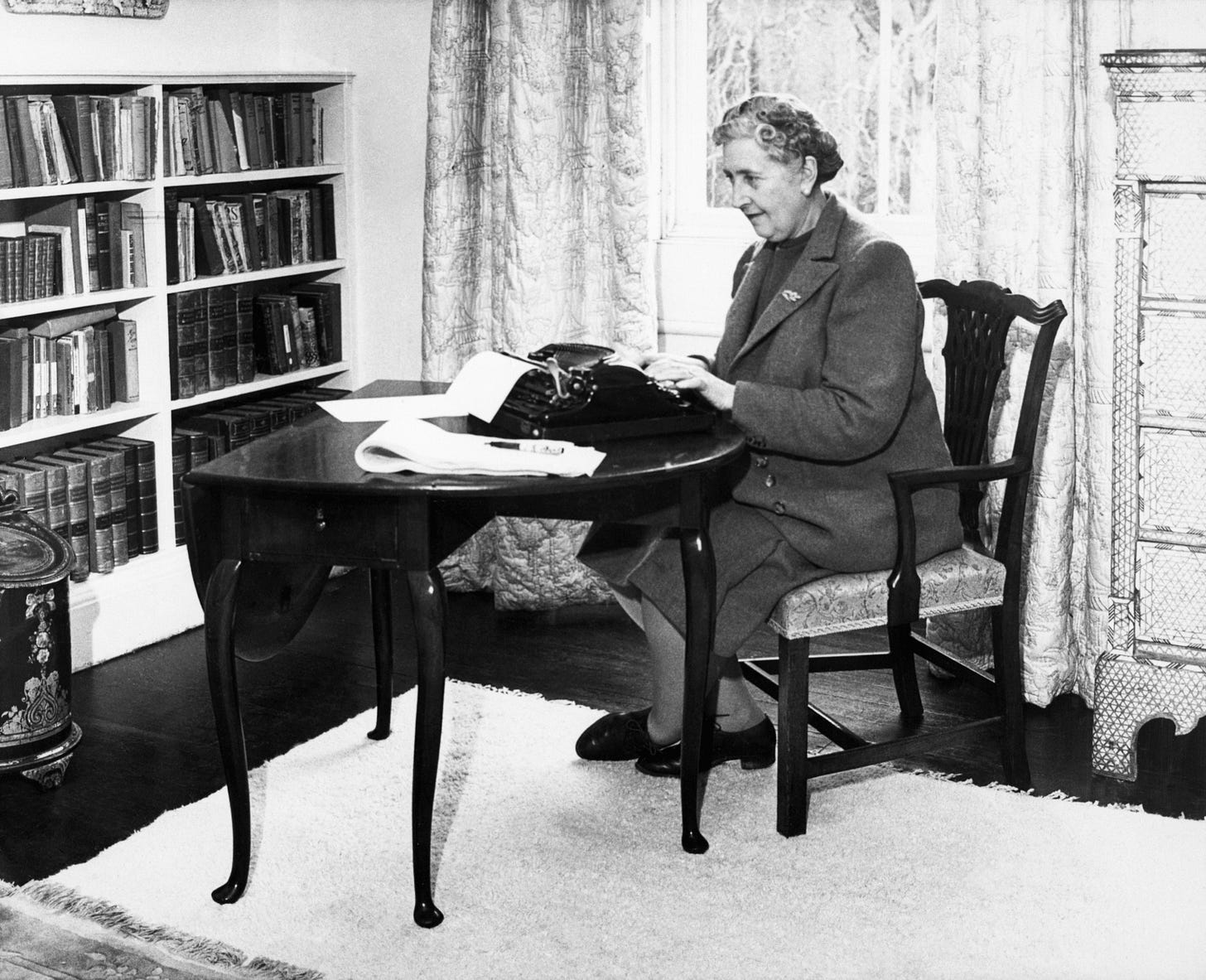

Agatha Christie, Still the Queen of Crime

Fifty years after her death, the British novelist continues to define the genre.

FIFTY YEARS AGO THIS WEEK, the world lost a writer who remains the top-selling novelist of all time, having sold, to date, more than two billion copies in forty-four languages: Dame Agatha Christie, the “Queen of Crime” who died at the age of 85 at her home in a small town in Oxfordshire. Christie’s career spanned most of the twentieth century. Her first mystery novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, which introduced her famous Belgian detective, Hercule Poirot, was written in 1916 and published in 1920. Her last novel, Sleeping Murder—featuring Christie’s other recurring sleuth, Miss Marple—was written in the 1940s and published in 1976 after her death. She redefined the detective genre and became its icon (and sometimes affectionately mocked its clichés). While she was certainly not the first successful female author in that genre, she established—with her contemporaries Dorothy Sayers and Ngaio Marsh—that the genre was one in which women were not only equal but dominant.

And, a half-century after her death, she has lost none of her ability to rivet the reader.

BORN IN 1890 AS THE THIRD and last child of a well-to-do upper-middle-class British couple, young Agatha (née Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller) was schooled at home until the age of 12; a voracious reader, she wrote her first poem at 10 and aspired to be a singer or pianist before she began to write at the age of 18. Her first short stories, mostly dealing with spiritualism and paranormal or quasi-supernatural themes, were all rejected; so was her first novel, Snow Upon the Desert (set in Egypt where Agatha and her mother had lived in 1907–08). Then, in 1920, The Mysterious Affair at Styles was published. By then, the former Agatha was married to military officer Archibald “Archie” Christie and had four years of service as a volunteer nurse in World War I behind her.

The Mysterious Affair at Styles was a success; it was quickly followed by more novels—one or two almost every year starting in 1922—and several collections of short stories. Christie’s star rose so rapidly in the next few years that when she disappeared for eleven days in December 1926, it became the stuff of international headlines. It’s somehow fitting that the queen of mystery should have a tantalizing mystery in her own life, though the reality of this episode may be more depressing than glamorous: Christie, devastated by her mother’s death in August of that year and further distraught over her husband’s extramarital affair, likely suffered a mental breakdown and may have had temporary amnesia. Christie’s marriage ended two years later; her writing career continued and flourished spectacularly. (She married again in 1930, to archeologist Max Mallowan whom she met on an expedition to Iraq, but kept “Christie” as her nom de plume.) Altogether, she wrote sixty-six novels, fourteen story collections, and the world’s longest-running—in fact, still-running—play, The Mousetrap.

Christie’s work is not great literature; but can she be seen, in her own way, as a great writer? I would say yes. Her books are often regarded as brilliantly constructed puzzles in which psychology and characterization take a distant back seat to the plot. Yet mystery writer Sophie Hannah argues that the criticism is unfair: “Each of her novels demonstrates a profound understanding of people—how they think, feel and behave—all delivered in her crisp, elegant, addictively readable style.” One reason some characters may feel flat, Hannah points out, is that we often don’t see all of their dimensions until the puzzle is put together: the big reveal suddenly upends most of what we thought we knew about one or more characters. Indeed, in many Christie classics (Death on the Nile, Peril at End House, A Murder Is Announced), the murderer isn’t the only one with a secret, and nearly every character isn’t what he or she seems.

Christie certainly created fully three-dimensional and memorable characters in her two iconic sleuths. The character of Hercule Poirot, a mustachioed, quick-witted Belgian retired police officer, was inspired by the Belgians she had encountered during the war—the refugees and the wounded soldiers to whom she had attended. Dandyish, neat to the point of fussiness, and sometimes accompanied by a Watson–like devoted and somewhat dim narrator/friend, Captain Arthur Hastings, Poirot is a man with a brilliant mind and a big ego, very proud of his “little grey cells” and never shy about reminding people of his brilliance. “You should not have given the star part to Hercule Poirot,” he tells a killer who has tried to use him as a cover for her elaborate plot. “That, Mademoiselle, was your mistake—your very grave mistake.” But he is also a man with a heart whose sympathy extends even to some of the murderers he catches: On occasion, he tacitly abets a suicide to allow a dignified exit instead of, in those times, a virtually inevitable hanging. His interactions with one such sympathetic murderer—someone whose descent into evil began with desperate love—at the end of Death on the Nile have a genuine poignancy.

An even more fascinating character is Jane Marple, an elderly, genteel spinster from the fictional village of St. Mary Mead who first appeared in a short story and then in the 1930 novel Murder at the Vicarage. In a very gender-specific contrast to Poirot, Miss Marple is humble and outwardly harmless—but those who’ve seen her at work know that she has a razor-sharp mind and a spine of steel underneath the meek exterior. Her crime-solving seems less intellectual than intuitive and practical, based on long experience as a people-watcher. (She easily figures out, for instance, that a scandalously unmarried artsy couple is actually married because of their very conjugal bickering.) A key element in Miss Marple’s method is to think of parallels that often seem bizarrely incongruous: In The Body in the Library, the grotesque sight of a dead blonde in flashy clothes and heavy makeup bafflingly dumped in the library of a respectable country home makes her recall a boy who played a prank on a teacher by putting a live frog in a clock. Sometimes, it makes people ask if she’s “funny in the head”; eventually, it’s going to make sense. (In her autobiography, Christie wrote that the model for this Miss Marple-ism was her own grandmother, who would often pronounce harsh and nearly always accurate judgments based simply on, “I’ve known one or two like him.”)

Christie’s supporting characters are also written with enough warmth and humor—or, sometimes, satirical bite—to come across as more than chess pieces in the author’s one-woman game. Even the walk-ons are well-painted with one or two pithy strokes, such as, “She had a deep bass voice and visited the poor indefatigably, however hard they tried to avoid her ministrations.” The appeal of Christie’s novels also comes from her skill at evoking the feel and texture of English life, be it the bustle of London or the village where everyone knows everyone and everything. (In The Body in the Library, local gossip quickly embellishes the shocking story of the dead blonde—she’s now said to have been found stark naked—and turns her into the mistress of the stodgy, very married homeowner.)

But Christie’s brilliantly constructed plots in their infinite variety are also a superb achievement. If some novels follow the classic formula of the “Golden Age” of detective fiction—a house, train, or luxury cruise ship with a narrowly defined circle of suspects—others bust that circle wide open: In What Mrs. McGillicuddy Saw! (a.k.a. 4:50 from Paddington), a train passenger sees a man strangle a woman in the window of a train going in the other direction when the two trains are briefly stopped next to each other; needless to say, no one will believe her, except for her friend Miss Marple.

In Toward Zero, the murder at the seaside home of an elderly upper-class woman doesn’t take place until halfway through the novel: The first half is the buildup, which creates a masterfully tense and creepy atmosphere and dwells on the complicated dynamics between a man, his wife, and his ex-wife for whom he may still have feelings. (We’re still in Christie-land: you can’t necessarily trust anything you think you know about this trio.) In A Murder Is Announced, a newspaper ad announces an upcoming murder at a local manor; people show up expecting a fun murder mystery party, until things suddenly get real. In the last Miss Marple novel Christie wrote, Nemesis (1971), a dead man’s will asks the now-frail but still-indomitable detective to investigate an unspecified past murder, with just a few clues, on a tour of famous British houses and gardens. In the posthumously published Sleeping Murder, the events are set in motion by a young woman’s suddenly jolted memory of a murder she may have witnessed as a child.

The plots often involve elaborate alibis and misdirections that no real-life murderer has probably ever used: for instance, disguising the time of death by committing an extra murder, swapping the bodies, and ensuring misidentification. Or carefully planting self-implicating clues while setting up an ironclad alibi—and plotting to frame someone for both the murder and the fake clues. And yet Christie manages to make it all plausible—or, at least, gripping enough to achieve willing suspension of disbelief.

Not surprisingly, Christie’s novels often include material “problematic” not only by modern standards but by those of years ago. After World War II, her literary agent authorized her American publisher to scrub antisemitic passages from her earlier books. (These passages often seem to reflect the era’s unthinking casual bigotries more than active hostility: “He’s a Jew, of course, but a frightfully decent one,” a character in the 1932 novel The Peril at End House says about another character who is, in fact, genuinely decent.) A 1939 title that contained the n-word was altered for publication in the United States even in 1940, to And Then There Were None. More recently, American Kindle editions of some of Christie’s works have bowdlerized the text to remove jarring lines such as a British tourist’s reference, in Death on the Nile, to the “disgusting” eyes and noses of local children. Some may also bristle—I did—at the conclusion of Evil Under the Sun in which a successful entrepreneur cheerfully agrees to marry a man who tells her, “You’re going to give up that damned dress‐making business of yours.” (Christie’s musings on women’s roles in her autobiography make it clear that such passages reflect her actual views, or at least the views she wanted to present to the public.)

But social progress needn’t translate into censoriousness toward less progressive attitudes in works from the past. We can still enjoy Christie’s books and see nuance in her portrayals of characters whom one could regard as offensively stereotyped: The cook Mitzi in A Murder Is Announced, a postwar Eastern European refugee who is probably Jewish, is treated as a comical figure because of her broken English and her persecution complex—but she also turns out to be far more astute and courageous than anyone realized. And we can appreciate the paradox of Christie striking a trad-wife posture while married to a man thirteen years her junior whose career was vastly overshadowed by hers.

A 2008 episode of the famous British time-travel show Doctor Who which posited a fanciful theory for Christie’s 1926 disappearance revealed that her books are still being printed and read in “the year five billion.” At least in the year 2026, people keep reading and the film and television adaptations keep coming. One may like or dislike some of the new versions, which often try to modernize the originals’ racial and gender politics in less than felicitous ways. (And, for those of us who have seen the 1989-2013 ITV Poirot, there will never be a more perfect version of the Belgian detective than David Suchet’s.) But if nothing else, these adaptations are a clue that the Queen of Crime still reigns.

Is she a great writer? I would say so. The Murder of Roger Ackroyd represented a first in the mystery genre. If And Then There Were None isn’t the best example of a “locked room” mystery, it’s one of them. Witness for the Prosecution has a great twist which also shows Christie’s perceptiveness about human nature. Although there were common elements in her works, such as the richness of the supporting characters and misdirection in her plots, she managed to keep her writing fresh.

I saw "Ten Little Indians" as a pre-teen in 1965. I enjoyed it so much that I read the novel "And Then There Were None" afterwards. OMG - I still remember at how utterly shocked I was at the ending of the novel, so completely different from the "happy ending" of the movie. There was a recent TV series made of the book, which is closer to the novel's ending, but it still leaves out the final (and best) scenes of the book, where the frustrated police cannot come up with a scenario that explains all the murders. Finally we get the startling "message in a bottle" that reveals the killer's surprising motivations and how it all happened. Absolutely brilliant. Agatha Christie is one reason why grew up to be a passionate lover of books, which I remain to this day. Thank you Cathy!