Ali Velshi’s Lucky Life

In his new book, the MSNBC host draws inspiration from his family, the duties of citizenship, and the nation of Canada.

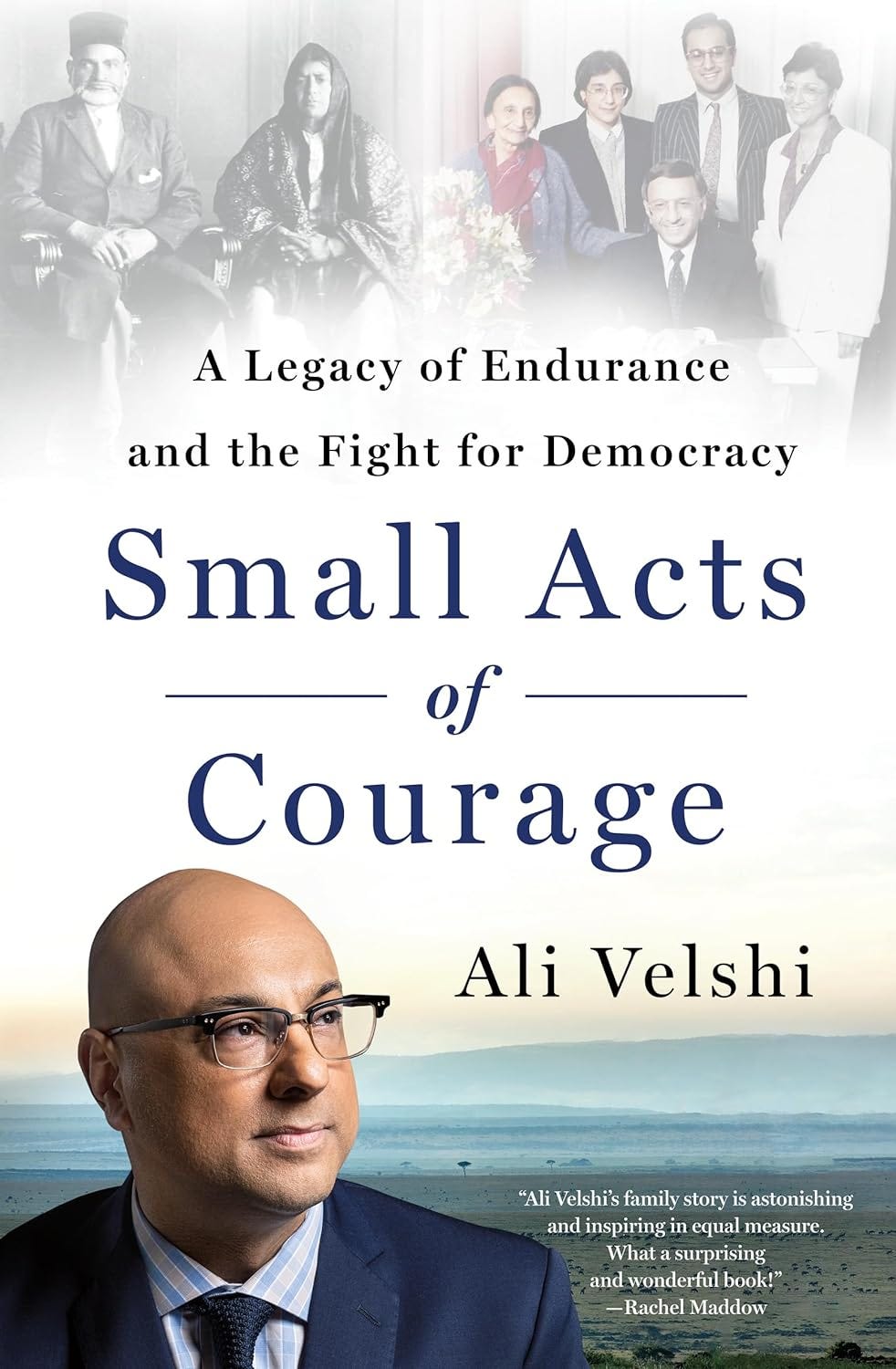

Small Acts of Courage

A Legacy of Endurance and the Fight for Democracy

by Ali Velshi

St. Martin’s, 304 pp., $30

IT WAS JUST ANOTHER STEP UP in Ali Velshi’s perpetually successful broadcast career. After paying his dues at various TV news gigs in Toronto, including a stint at Canada’s Report on Business Television—ROBTV, amusingly—he was hired for a job in New York City at CNN’s business reporting arm, CNNfn. He lined up an apartment in New York City and, after a paperwork delay, was all set to get on a plane to start his new role.

There was only one problem: It was September 11, 2001.

According to Velshi’s new book, Small Acts of Courage, CNN told him after the attacks that the situation in New York was “all hands on deck. We need you down here.” With no planes in the sky and having just sold his car in preparation for his new life, Velshi retrieved his 750cc Honda Hawk from his parents’ garage in Toronto and made the 480-mile trek to the Big Apple on two wheels.

Along the way, he had to get his paperwork approved at the border crossing office in Niagara Falls. As he produced his passport and a copy of his visa, it dawned on Velshi that, here he was, a brown Muslim man who had recently been in training to get a pilot’s license, seeking entry to the United States “less than forty-eight hours after the worst terrorist attack on American soil, an attack perpetrated by a bunch of brown Muslim guys with box cutters who’d pulled off the crime of the century by training to get their pilot’s licenses.”

But, in fact, the border guard “couldn’t have been more genial and kind,” Velshi recounts. “There was no suspicion, no feeling of conflict or asking me a bunch of questions.”

Welcome to the life of Ali Velshi. As the avuncular MSNBC host would be the first to admit, it is a life of privilege and good fortune. Small Acts of Courage, Velshi’s fourth book, is a kind of celebration of his family’s journey into brightness—a journey that began more than a century ago in India and brought them to Canada and the United States, by way of South Africa and Kenya.

It is a rich and mostly upbeat family history, one that Velshi, 54, recounts with evident pride. His paternal great-grandfather, Velshi Keshavjee, whose first name was adopted as his family’s surname, moved from India to South Africa in 1901, a journey that included a swim through shark-infested waters. His son Rajabali, Ali’s grandfather, was, as a young child in Johannesburg, literally carried about on the shoulders of Mahatma Gandhi, who spent more than two decades in South Africa. Rajabali became a student at Tolstoy Farm, an ashram that Gandhi founded.

As might be expected from someone who hung out with Gandhi, Rajabali held progressive views. He made sure that his daughters were educated and, as chair of his jamatkhana’s education board, urged others to do the same. Ali, who was born after his grandfather passed, quotes a speech Rajabali gave while on the education board: “My two daughters are at university. They will each be marrying one of your sons, so you will have two educated girls in your families. Can you please educate your girls so that my sons can have educated wives, too?”

ALI’S PARENTS, MURAD AND MILA, ran a successful bakery that served the black townships of Pretoria, South Africa. They moved to Nairobi, Kenya, in 1960, when apartheid became too oppressive. In 1971, when Ali was a toddler, the family moved to Canada; that’s where Ali grew up and lived until New York came knocking. His parents operated a travel agency chain in Toronto, and participated greatly in the life of their community. Murad Velshi became the first Muslim and first South Asian elected to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Mila Velshi served as president of a professional women’s club as well as on the Ontario Council for Citizenship and Multiculturalism and the Ontario Judicial Council.

Ali Velshi became a U.S. citizen in 2015, shortly after he left CNN for Al Jazeera on his way to MSNBC. This happened around three years after a key conversation with his then-CNN colleague Ashleigh Banfield. She had asked him why he had not availed himself of this opportunity and he had given a dismissive response (“some dumb joke about not wanting to deal with jury duty”). Banfield lit into him. “Being a citizen of this country is not something to be taken lightly,” she scolded. “You live in this country. You benefit from its services and infrastructure, and if you’re planning to stay here, that comes with rights and responsibilities. This is not a joking matter.”

Velshi eventually did come to take a more sober view toward his citizenship. But he also contends, somewhat oddly, that he never really “understood what it meant to be a citizen” of the United States until May 2020, when he was shot in the leg with a rubber bullet “by an armed agent of the state.”

This transformative event occurred in Minneapolis, when Velshi was covering protests in the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd. The moment, he recalls, had been free of violence until police opened fire—fully aware, Velshi believes, that he was a journalist. “That rubber bullet told me, ‘You’re in this fight. You’re not watching it anymore. You’re in it, whether you want to be or not.’”

This “epiphany,” he continues, “is what led to this book.”

HAVING NEVER BEEN SHOT, I hesitate to be dismissive of Velshi’s reconceptualization of American citizenship based on his receipt of a bullet to the leg. His take on this does seem a bit contrived. But perhaps Velshi’s stretch is forgivable, given what he’s reaching for—a vision of a better world that can be achieved through commitment to principle and individual acts of courage.

Velshi grew up in Toronto on what he recalls was a “WASPy” street. His family was culturally Indian, with Kenyan décor and “dinner table conversations about South Africa.” His parents were refreshingly broadminded. From the book:

We kept the traditions that were important to us, Indian food and Indian movies with my grandmother and religious instruction at the jamatkhana, but outside of those things, my parents believed that good things come from exposing yourself to lots of different ideas. Never once did they think of these outside influences as diluting or diminishing who we were or what was important to us.

As residents of Canada, the Velshis seem to have been remarkably untouched by anti-Indian, anti-Muslim, or anti-immigrant bias. Velshi gives credit for this to Canadian Prime Minister Lester Pearson and his successor, Pierre Trudeau, who in the 1960s and 1970s put out the welcome mat for immigrants, understanding the essential role they had to play in the country’s future economic growth. Canada, he says, learned long ago “what America still has not learned—that refugees are a good bet.”

Canada, in Velshi’s telling, is a utopian dream world for immigrants, where English and native languages are taught side-by-side. The message, Velshi writes, is: “You are welcome here. We will not only give you the tools you need to get ahead in this new culture, but we’ll help you retain your own culture as well.”

Throughout the book, Velshi holds up Canada as a beacon of light, in stark contrast to the darkness that shrouds life and politics in the United States, as when cops shoot at journalists. At one point, after noting how elections in the United States have come to include tugs of war over the use of mail-in ballots and the strategic closing of polling places, Velshi declares, “None of that shit exists in Canada.”

It seems at times that Velshi is making the case that life is just better in Canada—which may be true but is still sort of irritating. Most people don’t get to choose what country they live in or continent they live on. I think Velshi’s intent, though, is to invite optimism over what can happen in any country, if people make the necessary commitments to freedom, democracy, and the common good—what he calls “the grueling, thankless grunt work of citizenship.”

IN SMALL ACTS OF COURAGE, Velshi recalls a pivotal moment in the life of his older sister, Ishrath. Just before the family emigrated from Kenya to Canada, they returned to visit relatives in South Africa and, while there, stopped by the Pretoria zoo. Ishrath, then 9, innocently got into a line of kids waiting to take free horse rides. She was not allowed to do so, because of the color of her skin. She spent years processing the experience, which, Ali notes, “really pissed her off.” She would go on to become an executive aide to two members of the Toronto city council, helping ordinary citizens navigate problems, from leaking roofs to cracked sidewalks.

“My sister,” he beams, “identifies well with people who have a grievance. She loves righting wrongs and taking up lost causes, and she’s not afraid of anybody. She’s also one of those people who cares, genuinely cares, about making people’s lives better.”

This is the heart and soul of Velshi’s book: That it is within the power of ordinary people to bend the arc of the moral universe toward justice. His family is proof of this. But his own experience instructs him on how hard it can be.

In 2020, a few months after Velshi was shot in the leg with a rubber bullet, then-President Donald Trump, on the campaign trail, began mockingly recounting this incident, getting almost every detail wrong. “I remember this guy Velshi,” Trump told his followers, as part of a broader attack on the press. “He got hit in the knee with a canister of tear gas and he went down. He was down. ‘My knee, my knee.’”

Trump purportedly went on to call this a “beautiful thing,” how the police went after a journalist “after we take all that crap for weeks and weeks. . . . Wasn’t it really a beautiful sight? It’s called law and order.” The crowd cheered.

This is the kind of political culture—ignorant, unhinged, reflexively violent—that Trump has fomented in America. It’s going to take more than a few small acts of courage for our nation to get past that.