Are You Experienced? Are You Confused?

Patricia Lockwood’s latest novel is full of amusing episodes but refuses to cohere into a larger whole.

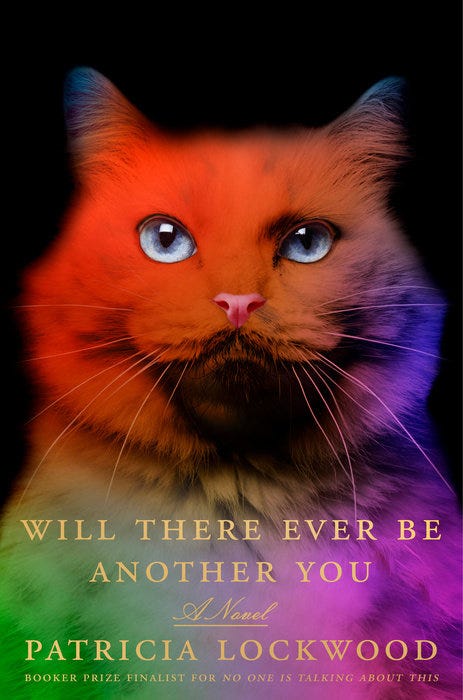

Will There Ever Be Another You

by Patricia Lockwood

Riverhead, 256 pp., $29

THERE IS NOTHING MORE TEDIOUS THAN LISTENING to someone earnestly explain to you the insights they had while on a mushroom trip. I shall illustrate.

Once, while deep in the embrace of Psilocybe cubensis, I discovered the funniest thing in the world, a joke that may very well undergird all of creation. I did what I always do when I have a major epiphany: call my old buddy Joel. He patiently listened as I explained: What if you had a friend who was deeply into the occult, but it turned out he was really Tom Bombadil? (You know, from The Lord of the Rings?) The joke is extraordinarily funny in itself, of course, but it gets even funnier when you take into account the kind of relationship my friend and I have. You see, I often play to the type of the somewhat-unstable pal who occasionally Delves Too Greedily into forbidden knowledge. He, for the purposes of this analogy, is the relatively normal guy who—

I will stop here, because I think my point has been made, and because I want only to invoke the concept of tedium, not subject you to it. My friend very kindly listened to me for a while before telling me had had to go take care of his kids. I then left him a series of harmlessly deranged voicemails. He informs me these were very funny and not at all worrying.

I say all this because if you’ve never had the tiresome experience of listening at length to a friend whose consumption of psychoactive substances has filled their mind with dreams of absolute reality, Patricia Lockwood’s newest novel, Will There Ever Be Another You, will serve as a decent proxy.

Styled as a novel, the book is essentially a memoir covering several disparate episodes: Lockwood’s time dealing with the effervescent-yet-dreadful brain fog of long COVID, the identity-shattering experience of caring for her very ill spouse, and, yes, the time she did a bunch of psychedelics while trying to make sense of classic literature. (“The summer before, I had tried to rewire my brain with mushrooms, but succeeded mainly in becoming temporarily psychic and reading Anna Karenina so hard I almost died.”) It is frequently funny, and it is occasionally beautiful, but after reaching the end of the novel, one is left with the inescapable sense that there must have been a better way to spend one’s time.

Lockwood claims (in the first-person narration of the novel itself, but later reiterated in an IRL interview with the New Yorker) that she aspired for Will There Ever Be Another You to be a “masterpiece about being confused.” Confusion is certainly much in evidence: The text jumps between first-, third-, and, briefly, second-person descriptions of Lockwood’s thought processes while dealing with a brain fog that refuses to lift even in her recounting of it. In particular, the book’s first portion—written while its main character is still deep in the misty midst of that brain fog—is a twirling jumble of narrative incidents, dialogue flying in from unclear sources, and low-grade panic:

Before she learned of the existence of “alien hand syndrome,” she had tentatively diagnosed herself with a new illness called Who Foot Is That. The main symptom was gasping when you saw your own foot. . . . The CEO of Texas Roadhouse killed himself, no longer able to bear the continuous ringing in his ears. In his lengthy obituary, the newspaper printed the quote: “We’re a people company that just happens to serve steaks.” The sentence stayed with her long afterward, shrilling at her temple like a mosquito. We’re a people company that just happens to serve steaks, she would say to herself, surprised by the sight of her own foot.

There is quite a bit to like in this section, as disorienting as it is. The narrator and her family are on a trip to Scotland when she first falls ill, and her mother’s recurring, doomed quest to get iced tea at a restaurant is a great gag:

Between the time her mother had gone into her hotel room and the time she reappeared in the hall, her jeans had become wet. They would not dry for the rest of the trip. The wetness came to represent, in the rest of their minds, the iced tea she could never get. “Tea . . . with ice?” She would ask hopefully, making a series of gestures to communicate the concept of iced tea, and be brought a cup with three cubes in it by someone who looked almost medically concerned.

Lockwood has always been at her best when writing tight, aphoristic jokes. Profiles of her often describe her as the “poet laureate of Twitter,” something it makes sense to foreground: She is responsible for at least two of the greatest tweets of all time. (“.@parisreview so, is Paris any good or not” is the first, and the “jail for mother” tweet is the second.) Her first novel, No One is Talking About This, was a finalist for the Booker Prize; half of it whooshes by in the form of a series of short scenes interrupted by tweet-length jokes.

Unsurprisingly, there is at least one decent joke or delightfully surprising turn of phrase every few pages in Will There Ever Be Another You. But by the end of the second section, one may start to feel that this ever-expanding verbal miasma isn’t cohering into much of anything; the feeling is inescapable by the novel’s end. Over the course of the second half of the book, the narrator has met the actress Anne Hathaway (only ever referred to as “Shakespeare’s wife”), about whom she says: “She was dressed as an equestrian and I was dressed as a female centaur; our turtlenecks were so total that it was a wonder either of us could breathe.” She has gone to a confusing German festival with her family. She has tried to get a TV show made out of her 2017 memoir, Priestdaddy. She has taken care of her husband, who was very ill. She has attended a metalworking class. She has included, for our perusal, an eighteen-page mushroom journal about Anna Karenina. The whole thing. She just drops it in there, with everything else.

TO RETURN FOR A MOMENT to my opening anecdote: When during a vivid psychedelic experience you call up a beloved friend to declaim about Tom Bombadil, you are referring to the character in a maximally expansive way. Your starting point is a combination of every thought or conversation you’ve ever had about the character’s role in Tolkien’s legendarium. You then touch on how good a job the Magic: The Gathering designers did capturing Tom in a card for that venerable game. You come around to talking about the fact that his name is Tom, and your deceased father’s name is Tom, and isn’t that something, isn’t the universe full of connections, and oh, goodness, now you’re crying again.

My point is that having a conversation is difficult when one of the participants in it is sailing through a choppy sea of signs and signifiers, all of which are only privately comprehensible. I will not say that this grand progression of thoughts is meaningless per se, but it does function as a sort of private language, circumscribing its meaningfulness to a single person.

This problem repeatedly emerges in Will There Ever Be Another You—when Lockwood meditates on whether she can ever trust someone to play her in a TV show, for instance, or when she describes her relationship with her father. She makes references to these things in ways that only really make sense if one already knows what she is talking about for having read her other books and articles.

I did, which is how I knew what was going on each time the text became dependent on familiarity with the Lockwood Cinematic Universe. I had already read Priestdaddy and No One Is Talking About This and what seemed like millions of her tweets and some of her poems and many of her essays for places like the London Review of Books. When she references “the portal,” I know that this is what she called Twitter in No One Is Talking About This, but she does not explain this for the benefit of anyone who has not read No One Is Talking About This. People who have not read Priestdaddy will likely be left very confused about her father, who, thanks to a special dispensation from the Pope, is a married Catholic priest with five children. (One imagines Lockwood has grown tired of the elevator-pitch explanation of this unusual arrangement—he became a priest after converting to Catholicism as a married Lutheran pastor—but surely not all of her readers can be expected to have read her previous memoir.) Even the sections about her caring for her ill husband were more legible to me because I had read her London Review of Books article about the same.

Would the book be intelligible at all to someone not already well versed in Lockwoodiana? I cannot say for certain, but I suspect that it would not be. Further, is there really any reason this is styled as a novel instead of a memoir? I am aware that this puts me into a conversation about the nature of “autofiction,” though I cannot spend much time there; I have not read Knausgaard. But I submit that what this really is, rather than either a novel or a memoir, is a collection of blog posts of a style that was most popular around 2012. It is built on an assumption that your reader knows the details of your life, since they have presumably read your earlier posts. A distracted, airy collection of random thoughts feels appropriate in that setting. But in a novel, one expects (or at least I expect) the ability to make sense of the text without already knowing all the details of the author’s life. I expect, I suppose, a text that provides its own context.

One scene in the book finds Lockwood having a literary conversation with an author identified as “Susanna.” Susanna also suffers from a fog-inducing sickness, or, as the book puts it, “it happened to her too, after a book tour in America; some virus, she doesn’t know where or when. Ten years in a dark room, writing about a man in a maze.”

Now, I know this character is Susanna Clarke, author of Jonathan Strange & Mr. Norrell and Piranesi, and famous sufferer from chronic fatigue syndrome. I know all this because, well, I have a Piranesi tattoo. But is what Lockwood provides enough for the uninitiated reader to understand who Susanna is or why there is a connection between these two writers? Or is it not important that they do understand any of that? Is the point to see things passing by that you do not comprehend?

Regardless, once Lockwood invoked Clarke, I could not help but compare this book to Piranesi. Piranesi could certainly be described as a “masterpiece about being confused.” Its main character resides, or is trapped, in an endless labyrinthine House of marble statues; its bottom levels are flooded, and as far as he knows, he is one of only two people alive in the whole universe. The reader learns quickly that something about the House has been affecting his mind, stealing his memories and changing the way he thinks; he refers to, without noticing it, things he could not possibly understand if his life was as he believes it to be. Where do the empty crisp packets come from, if there exists only the House? Why does he know what crisp packets are?

The joy of Piranesi is not to be found in its plot; many of its twists and turns can be easily predicted by any remotely genre-savvy reader. Instead, the joy of Piranesi is in how it forces the reader to dwell inside the mind of this very strange, very trapped (and very good) person. Piranesi models the experience of confusion all while telling a beautiful story that is full of rich portraits of its few characters. Will There Ever Be Another You is a disorienting jumble of thoughts that stubbornly refuse to cohere. Perhaps this is a strength: It is intended to be a depiction of disorientation. Perhaps my frustration with the novel is entirely a matter of taste, or a sign of closedmindedness on my part. Perhaps I am, as I have always feared, a philistine. But faced with the twin options of Piranesi and Will There Ever Be Another You, I know which one I will choose, every time.