Before the Internet, There Was Harry Smith

The lifelong collector, archivist, and eccentric helped establish the canon of American folk music by compiling a legendary anthology of rare recordings.

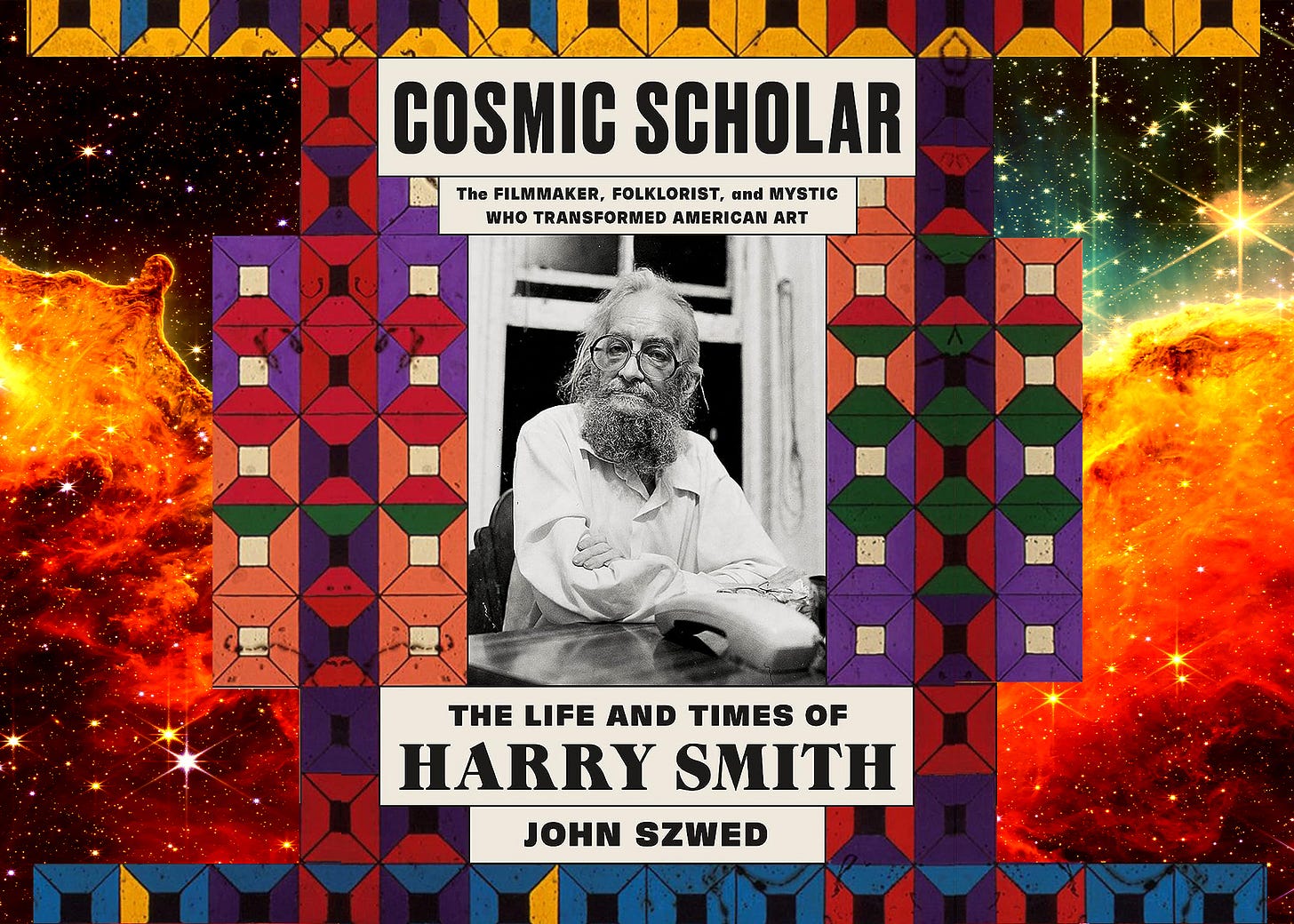

Cosmic Scholar

The Life and Times of Harry Smith

by John Szwed

FSG, 416 pp., $35

THE RECORD CRACKLES. The guitar strums. A man’s voice keens to us through the ages: “Get down, get down, little Henry Lee / And stay all night with me.” He is not the first to sing it and he won’t be the last.

The song is called “Henry Lee,” and the singer’s name is Dick Justice. “Henry Lee” is a traditional folk song whose origins extend back to eighteenth-century Scotland. Justice was a singer from West Virginia who traveled and performed throughout the United States in the early twentieth century. In 1930, his recording of “Henry Lee,” made the prior year for a regional label, was released. But Justice had recorded his song the year of the crash that would eventually bring about the Great Depression, which decimated the nascent recording industry and made sparsely distributed records like his difficult to find. Today, though, Justice’s version of “Henry Lee” is renowned the world over. Nick Cave recorded the song in 1996; he sang his version as a duet with P.J. Harvey.

How did an Australian rocker like Cave come to record a Scottish murder ballad made famous by an obscure West Virginian folk performer? The answer lies with a man named Harry Smith. While not a musician, exactly, Smith exerted an enormous influence on popular music. He was revered by the likes of Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, the Grateful Dead, Beck, Sonic Youth, and countless others. He earned that reverence thanks to a passion project, the three-volume Anthology of American Folk Music, first released in 1952. Smith dug through his extensive collection of folk recordings made in the late 1920s and early ’30s to put together the eighty-four song compilation. Juxtaposing blues, folk, country, and gospel, the Anthology offered a panorama of the “Old, Weird America,” to use Greil Marcus’s term, at a time when booming postwar affluence made the country’s agricultural past seem almost mythically distant.

For anyone else, the Anthology would have been the crowning achievement of a lifetime. But for Smith, it was a footnote. A restless polymath, an eccentric in the fullest sense of the word, he did enough to fill a dozen lifetimes with achievements. Yet he died penniless in a seedy hotel at the age of 68, with much of his work either lost or destroyed, like some eternal drifter from one of the folk songs he gathered.

John Szwed tells Smith’s story in Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith. A Zelig of the counterculture, Smith knew everyone, from Allen Ginsberg to Timothy Leary to Patti Smith. Yet he was also elusive, vanishing for months or even years at a time; he had few friends. Today, it’s natural to take Smith to be a prophet of the internet, a man by the spirit of Tumblr possessed. Yet there’s a wistfulness to this. As cultural knowledge becomes more diffuse and shorn of geographic or even physical context, an actually unique figure like Smith, a brilliant and slightly disreputable basement archivist, is all but unheard of. In his place, there are countless sub-Smiths, all of them curating their own little corners of knowledge with clean hands on gleaming laptops, and not one of them ever quite reaching the breadth of Smith’s vision.

Describing Smith’s achievements risks taking things into listicle territory. He was an anthropologist, a filmmaker, a curator, a photographer, a magician, a babysitter, a drunk, a gadabout. Yet above all else, Smith was a collector. The impulse to collect anything and everything, from songs to Seminole textiles to medieval tomes of alchemy, grew into an obsession for him. Among midcentury figures in the American scene, only Andy Warhol rivals Smith’s devotion to the act of gathering. But Warhol placed himself at the center of a cultural powerhouse—“The Factory,” as he called his studio. Smith remained at the periphery, a wandering archive with no fixed address.

LIKE KEN KESEY, Smith was raised in the Pacific Northwest. Two influences dominated his upbringing: esoteric religions and Native American culture. His parents were Theosophists. Their knowledge of a wealth of left-field religious beliefs provided Smith with a lifelong interest in such subjects as the Kabbalah and universal consciousness. As a child living in Anacortes, Washington, he frequently visited the nearby Swinomish reservation, observing rituals that no other white person saw, and recording his findings. His diligence and intelligence were evident from a young age, drawing the attention of prominent anthropologists. Great things were expected of young Harry Smith.

But academia was an ill fit. He argued with his University of Washington professors, believing himself to be smarter than those who presumed to teach him, and rarely came to class, preferring to spend more and more time in the field, among the Swinomish. As an acquaintance put it, “He began like a college professor on a field trip and then became the field trip.”

From there, he decamped to San Francisco in the mid-1940s, just as the city was coming into its own as a cultural center. Poets like Jack Spicer and Robert Duncan wrote mystical verse about falcons and radio messages from Mars; jazz musicians played at after-hours clubs, honing the new “bop” sound. And Smith was there, always. Not just as an observer, either. He convinced jazz club owners to let him paint murals on the walls, intricate designs inspired by the music played there. He spoke to Thelonious Monk for hours on end, even when the famously reticent musician would speak to no one else, discussing music and different ways to represent it visually. And he collected, constantly. Jazz records, blues records, folk records. String figures, paper airplanes. Some of it he used for his paintings, but much of it remained in boxes he hauled from one flophouse room to another.

In 1951, he moved to New York City, which would remain his home base for the rest of his life. New York exists, if nothing else, to provide space for eccentrics like Smith. His different apartments were cramped with his books, his paintings, his collection of Ukrainian Easter eggs. He also began to explore filmmaking, producing “non-objective” films by painting directly on the film itself. The results are at once trippy and wholesome—Sesame Street by way of Frank Zappa. He always struggled to present his work to the public, though. It made demands on the viewer, for one thing, with little precedent at the time in Hollywood filmmaking.

Smith himself was demanding, too. He pestered audiences during screenings, berating people for not understanding, sometimes even tearing the film reels off the projector and throwing them into the street. Much of Smith’s work was lost during his lifetime; though some of it was cast into various landfills by impatient landlords, some of it was destroyed by his own hand. It is the spirit that remains.

READING COSMIC SCHOLAR NATURALLY PROMPTS a question: Was Harry Smith ahead of his time, or did he exemplify it? The restless collector died in 1991 and never got to experience the internet as we know it today. Much of his surviving work that was once housed in the storage rooms of university libraries can now be accessed by virtually anyone with a laptop and a wifi connection. You can view his non-objective films at your leisure on YouTube, safe from the prospect of Smith throwing a tantrum in the middle of the screening. Log on to Spotify and you can find different compilations of the original Anthology tracklist, with alternate versions and covers available with a quick search.

It staggers the mind to consider what Smith would have come up with had he lived into the broadband era. Would he have catalogued Thai pop songs on TikTok? Collected the unique textiles of anime cosplay conventions? By gathering up digital ephemera that would otherwise have remained scattered, diffuse, and idiosyncratic—as would have been the fate of his folk song recordings without his era-defining redaction—what cultural architectonics could internet-age Smith have created for future artists to build upon?

Yet one suspects that Smith may have disparaged the bodiless, boundless internet. He was a thoroughly analog creature. Research, data-gathering, interviewing—these were, for him, profoundly physical acts that demanded his whole being. He spent hours in esoteric bookstores, befriending the clerks and frustrating acquaintances who wanted to move on and get an egg cream at the diner next door. He lived on the road for weeks at a time, even months, as he ingratiated himself with Native American tribes, recording each song and custom the elders recalled until they had no more to offer him. This was midcentury America, after all, the Age of the Gizmo, when recording devices and film cameras were becoming commercially available to the middle class, delighting enthusiasts everywhere. And there were no digital cameras operated solely with the push of a button back then. The film had to be loaded, gears had to be wound—just the sort of rituals of physicality that Smith exulted in.

Smith’s approach to social interaction was also deeply analog. For all his proto-hikikomori tendencies—the days and weeks he spent alone in his apartment making films and organizing his collections—he also recognized the need to get out of the house. To research, yes, but also to schmooze. A thread pulled through Cosmic Scholar is Smith’s utter shamelessness, or perhaps selflessness, when it came to asking for money. Constitutionally incapable of holding down a job, Smith became dependent on handouts from more affluent friends who appreciated his work.

On multiple occasions, he asked Jonas Mekas to write up his need for funds in Mekas’s influential film column for the Village Voice. (Considering Smith a “genius” of experimental film, Mekas regularly obliged.) Jerry Garcia once offered to give Smith $10,000 per annum, an expression of gratitude for the Anthology and the world it opened up. Near the end of Smith’s life, he was taken care of by Allen Ginsberg, who fed and housed him for several years until, Smith’s demands growing unbearable, he arranged to have him set up with housing and light lecturing duties at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. Smith was broke his whole life, but he was fortunate to live in a time and place that put him in touch with many wealthy and influential patrons.

But in this way, he prefigured our current moment, too. Brilliant layabouts and eccentrics can now find audiences through Twitter and similar networks and then monetize that support through crowdfunding sites like the aptly named Patreon. Many aspects of Smith’s legacy are carried on in similar ways—old forms in new combinations, antique practices updated for online life. So do we continue the story of the twentieth century in the twenty-first: crossing high technology with ancient knowledge to create something new.

Today, in spite of the astonishing volume of information available to us in our glowing pockets, what we risk losing is the synthesizing, omnivorous intelligence capable of producing true historical knowledge. The internet flattens; the Singularity threatens what is singular. But Smith’s life can be an example to inspire a new generation of cultural archivists. Turn off the computer, Smith’s legacy counsels us, Leave the house, and commit yourself to understanding some part of our enormous human world.