Can the CHIPS Act Be Implemented Without Becoming a Byzantine Mess?

The semiconductor industry and the need for what Hamilton called “the steady administration of the laws.”

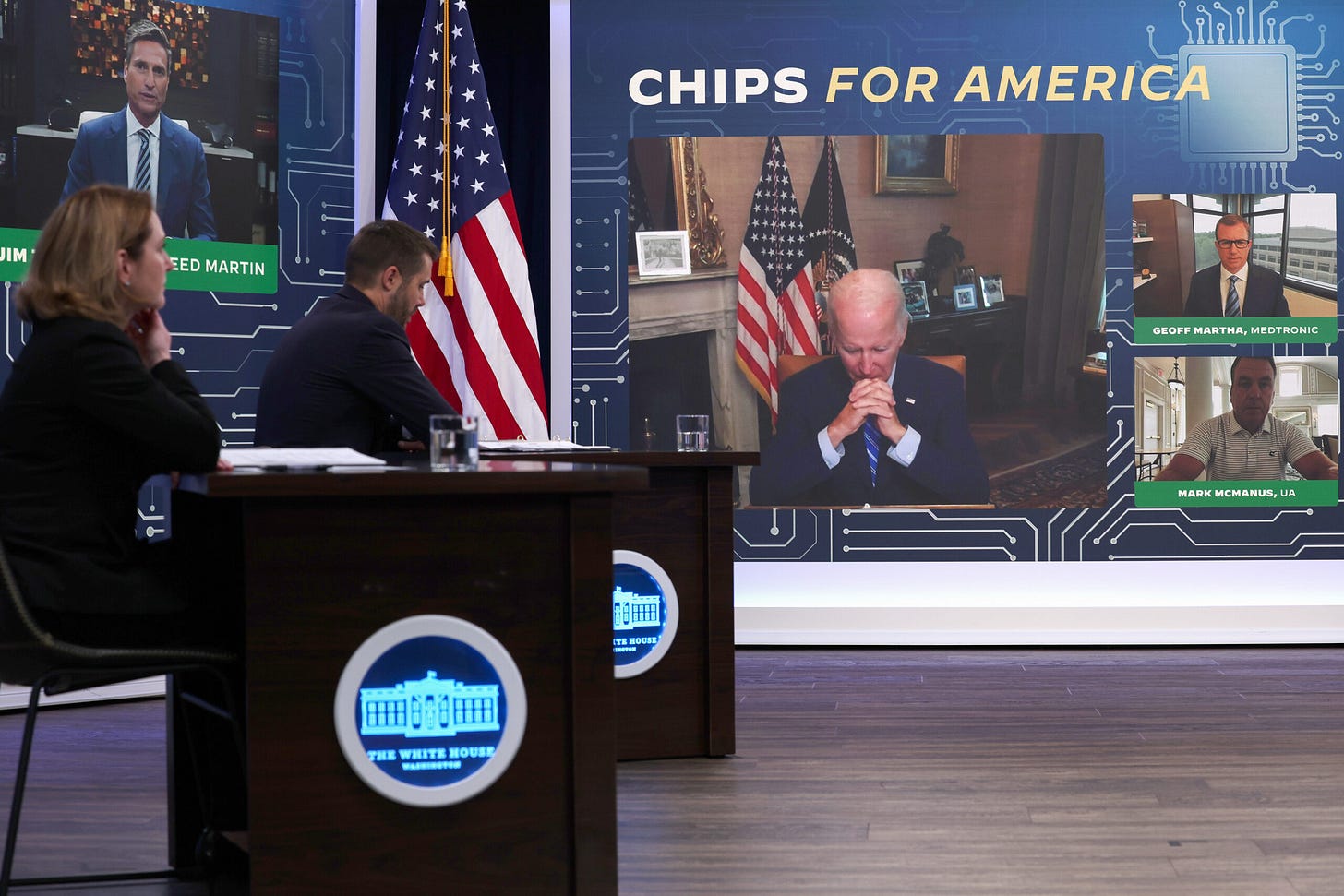

Last summer, Congress enacted the CHIPS Act to boost America’s ailing semiconductor industry, for the sake of reducing our reliance—and the world’s reliance—on China’s own industry. As the Biden administration now begins to execute that law, its next steps will reveal much about the administration itself. And if it follows through on its newly announced plan to water down Congress’s semiconductor policy with other domestic policies, it will illustrate one of the major problems in modern American administration.

In the constitutional debates swirling around federal administration today, one of the biggest issues is “delegation.” For a century, Congress has delegated immense and innumerable powers to federal agencies, in legislation that gives regulators practically open-ended discretion.

Among critics of the modern administrative state, the conventional argument is that Congress’s broad delegations of power and discretion turbocharge regulators, enabling them to swiftly assert regulatory power without the legislative process’s constitutional checks and balances.

This is true, but it is only part of the truth. Another part, perhaps less appreciated but even more important, is that broad delegations of power and discretion also deform administration.

The seminal argument for the Constitution’s executive power, Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist No. 70, shows us why. Hamilton wrote that the best government has “energy in the executive,” for the sake of not just national defense but also “steady administration of the laws.” He and his co-author James Madison famously knew that the legislative process would often be slow, difficult, and full of frustrations and compromises—indeed, that’s the legislative process at its best. But the executive process needs to be the opposite: Once the law is enacted, it needs to be executed swiftly and steadily, both for the government’s sake and for the people’s. The greatest threat to constitutional government, as Hamilton saw it, is the prospect of new laws slouching into irrelevance—a “disgraceful and ruinous mutability in the administration of the government.” (The “mutability”—the weakness and instability—of laws was one of Madison’s main criticisms of American government under the Articles of Confederation.)

Here, then, is the key problem of Congress delegating too many powers and too much discretion to the executive branch: It empowers agencies but it also undermines energetic execution, because an administration cannot execute the laws without first taking time to decide how to execute them. An agency with immense discretion must decide how to exercise that discretion; and an agency with the freedom to impose many different policies will inevitably find itself watering down some policies to facilitate others.

We’ve seen this play out for many decades, one administration after another, but perhaps never so clearly as in the Biden administration’s initial implementation of the CHIPS Act.

America’s national interests, and the interests of our allies and international institutions, depend heavily on reducing China’s power over the production of semiconductors. Congress, recognizing this, enacted a law providing tens of billions of dollars to strengthen America’s own semiconductor industry.

From the start of this legislative debate, however, it has been clear that reinvigorating our semiconductor industry will require more than just money. It also requires streamlining the many federal, state, and local regulations that make it difficult, if not impossible, to actually build chip “fabs” here at home.

The regulatory barriers were spelled out by Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology in a pair of reports issued in 2021 and 2022. Others see the problem too. When then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan last year, Taiwan’s own semiconductor executives questioned, as Politico columnist Alexander Burns put it, “whether American environmental and labor laws were consistent with the goal of nurturing a sophisticated industry.”

(And for what it’s worth, I put this issue front and center in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed flagging a few domestic policy issues that the House Select Committee on China should study.)

According to Burns, Speaker Pelosi “rejected the idea that there might be tensions between her political party’s grand economic and social aspirations, and the narrower aims of the CHIPS law.” But the facts soon suggested otherwise.

When the Biden administration announced its plan to implement Congress’s semiconductor law last month, the New York Times quickly observed that “the CHIPS Act is increasingly about more than, well, chips.” The administration layered on many other familiar Democratic policies: providing workers with “affordable, accessible, reliable, and high-quality child care”; promoting union labor (via “project labor agreements”); discouraging stockholders from selling stock back to the company (the increasingly demagogued “stock buybacks”); and more. The administration also announced that companies receiving funds from the CHIPS Act would need to “share with the U.S. government a portion of any cash flows or returns that exceed the applicant’s projections above an established threshold.” All of this in addition to the pre-existing layers of regulatory requirements for domestic manufacturing projects.

And unsurprisingly, companies are already balking at the administration’s demands. The Financial Times reported concerns from South Korean chipmakers. “We’re perplexed by these unexpected conditions. We’ve never seen anything like this for state incentives,” one executive told the FT, emphasizing the practical questions raised by the administration’s stated demands.

A separate editorial from the FT put it bluntly: “The White House is using a national security priority to tackle too many goals.” Industrial policy is already problematic enough; when it is used, the government needs to “set precise goals and stick to them.”

The problem, again, is not so much the CHIPS Act itself; whatever one thinks of industrial subsidies like this (and I’m no fan, to say the least), the CHIPS Act was straightforward, at least in terms of dollar amounts. But things quickly get more complicated due to the CHIPS Act’s incorporation of other laws expanding the factors that an administration can consider in granting or denying funds to an applicant. The FT editorial’s headline summed up the problem concisely: “The US Chips Act becomes a Christmas tree.”

There already were enough regulatory barriers standing athwart an American semiconductor revival; the administration’s multifaceted demands relating to Democratic social policies make energetic administration of the CHIPS Act even less likely. And would-be applicants may begin to wonder if it is better to await CHIPS Act funds for fiscal years 2025 or 2026, when a different administration might differently administer the law.

And Americans will be left to wonder: Can even the CHIPS Act—the most straightforward legislative initiative of the last two years, enacted for a plain and simple purpose of national security—not be executed energetically without meandering into a morass of other policy issues?

It’s not too late for the Biden administration to change its approach. More importantly, it’s not too late for Congress to enact amendments that would significantly reduce the Commerce Department’s discretion, for the sake of steady, swift, and successful administration of the program. Most importantly, it’s not too late for America to relearn the virtues of steady administration that Hamilton emphasized at the start. At least, one hopes not.