I have not commented much on the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas and the still-unfolding story of the baffling police failures in the handling of the active-shooter situation. This is mainly because I think the discourse around it vastly oversimplifies the burning question of what can be done to prevent such tragedies, but the aftermath of a massacre in which 19 young children died is not favorable to nuance.

But I’ll try.

The prevailing view is that the dead (who also include two teachers) are sacrificial victims to the gun lobby, to the peculiarly American obsession with the right of firearm ownership, and to Republican politics that block sensible gun control.

For the record, while I support the right to keep and bear arms, I also support many regulations that the National Rifle Association has adamantly opposed, such as more effective background checks (apparently supported even by a strong majority of rank-and-file NRA members) and limitations on magazine capacity, which seems to be a strong factor in the deadliness of mass shootings. I’m not a constitutional scholar, but I think that, while there’s a strong case for Second Amendment protections for individual gun ownership, the amendment’s reference to “a well-regulated militia” indicates that gun regulation is not at odds with such protections. I certainly have little love for the NRA’s brand of culture warfare and right-wing identity politics, or for the gun fetishism exemplified by the infamous Christmas photo tweeted in December by Kentucky Congressman Thomas Massie.

But.

I have serious doubts that sensible and realistic regulations can rid us of school massacres.

The Uvalde killer, Salvator Ramos, was able to buy two AR-15s and a vast quantity of ammunition legally after turning 18. Is that ridiculous? Yes, it is. Would sensible regulations have stopped him from getting the guns and the ammo illegally? Maybe. Or maybe not. Or maybe the regulations would have stopped Ramos, but not the next mass shooter.

We don’t have a very good record of keeping illegal things out of people’s hands. (See: drugs.) In the case of firearms, there is already a massive quantity of them in the country (some 350 million), including AR-15s. And modern technology, including 3D printing, would facilitate a thriving black market in new guns.

Gun confiscation isn’t going to happen. (The 1994 assault weapons ban did not do that.) You thought the War on Drugs was a disaster for civil liberties? Wait until we get a War on Guns. (Or a War on Abortion. But I digress.) And if you’re concerned about policies that disproportionately affect the poor and minorities … well, how do you think this one is going to play out? (The Stop-and-Frisk program in New York City, infamous for its racial profiling, was aimed at getting guns off the streets.)

This is not to mention that the discourse routinely conflates mass school shootings—which, however horrifying, are incredibly rare events—with gun homicides in general, or gun homicides of minors. These are entirely different problems.

I know there are the examples of other countries which we are urged to emulate: the United Kingdom, Australia, and Canada, all of which imposed more or less sweeping new gun restrictions after mass shootings and saw gun violence (including mass shootings) plummet. We can debate whether it’s a good or a bad thing that America has a more absolutist conception of individual liberty. But for whatever reason, the differences cannot be reduced to gun restrictions. For instance: the non-firearm homicide rate in the United States in 2020 (1.96 per 100,000 people) was nearly twice as high as the total homicide rate in the United Kingdom (about 1 per 100,000). In other words, if we eliminated all the firearm homicides and none of their perpetrators used substitute methods, we’d still have almost twice as many murders as England, relative to the population.

Fisher suggests that the 1996 gun ban in the U.K. had a strong effect on gun violence. But his own article shows that there were two mass shootings in the U.K. before the ban and two since (in 2010 and 2021). He notes that “the gun homicide rate is about 0.7 per million, also one of the lowest.” But again, is that due to the gun ban? A thorough analysis from the U.K. Home Office shows that overall homicide rate in England and Wales today is at about the same level as in 1980. (The U.S./UK gap was actually much larger at that point because the U.S. had a much higher homicide rate than it does now.) The homicide rate actually reached an all-time high after 1997, then began to drop around 2001. So one can’t easily draw conclusions about guns.

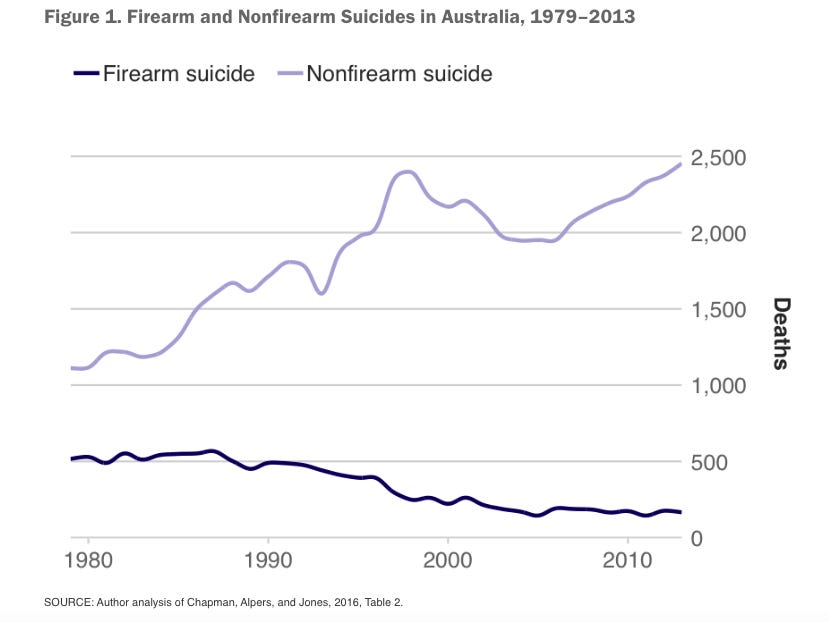

Australia, where gun homicides were already dropping before the 1996 gun buyback and the introduction of new restrictions on ownership, is also a complicated case. Fisher cites a 2011 item from Harvard’s “Bulletins” newsletter which concludes that the Australian program “seems to have been” highly successful in saving lives; but that item also concedes that some of the causal linkage is inconclusive and that the program is not “fully replicable in the United States” for a variety of reasons. A RAND Corporation paper updated in 2021 paints an even more complex picture of the cause-and-effect relationship. Also: while Fisher claims that the firearm suicide rate in Australia dropped while non-firearm suicides did not increase, this simply ain’t so.

None of this is to say that there’s nothing we can do to reduce gun deaths or mass shootings. But “Why can’t we be more like the U.K. or Australia?” is a non-starter.

Obviously, there’s a lot of nonsense “on the other side,” too. People have been circulating a 2018 paper by John R. Lott claiming that the United States doesn’t actually have more mass shootings per capita than other developed countries. If the name “John R. Lott” doesn’t automatically make you suspicious, there’s also the fact that something this counterintuitive needs to meet a really high standard of proof. As it happens, the Washington Post’s Glenn Kessler (who is hardly a lefty ideologue) pretty thoroughly debunks Lott’s claim, demonstrating that if you remove terrorist attacks with multiple assailants, the United States does, by far, lead the developed world in mass shootings.

There’s also this from Jordan Peterson:

Keeping mass shooters’ identities anonymous might have worked in 1996. But in the age of the Internet and the social media? Any attempts to keep their names out of the news would likely end up generating even more curiosity and interest. We might as well discuss proposals to zap mass shooters into another dimension. It ain’t gonna happen. (Also, what happened to free speech?)

And don’t get me started on this histrionic post from Dave Kopel at the Volokh Conspiracy decrying “blood libels” against the NRA.

I’m more than willing to join in skewering Republican evasions and platitudes. But I also know that the very understandable urge to Do Something in the wake of a horrible tragedy—whether it’s a school shooting or a terror attack—can lead us down the wrong path. The tragedy does not negate the need to ask what can and can’t work, and what can have unintended consequences.

Also: I think we should reject hyperbolic statements about how the Uvalde shooting means that America is broken, or has crossed a moral line past which civilization cannot endure. I’m not sure why it’s this event and not all the far more numerous deaths of children in “ordinary” crime, or from child abuse and neglect.

At the same time, the polemics around Uvalde do show, once again, that our discourse is broken, and that we should try to rebuild it. Right now, Republicans are strenuously trying to avoid the obvious fact that high-performance firearms do facilitate mass shootings—and sidestep the issue of whether mass shootings of children can be seen as acceptable collateral damage from gun rights.

Meanwhile, too many Democrats send signals suggesting that they do want U.K.-style firearm ban and ignore the perspective of non-fanatical gun owners who believe they need a gun for protection. Perhaps the dialogue could start from there. Perhaps we can talk about meaningful harm reduction, even if there’s no full solution to the problem. But in any such conversation, we also have to stick to the facts.

The Depp v. Heard Battle Royale

The Amber Heard/Johnny Depp trial (in case you’ve been in a cave somewhere, the former Pirates of the Caribbean star is suing his actress ex-wife for defamation, seeking $50 million in damages over statements suggesting that he abused her during their marriage) is obviously celebrity porn, but it’s also more than that. Depp is basically accusing Heard of being a faux victim—of not only making up her claims of abuse, but being abusive toward him.

There are First Amendment questions involved, since the focus of the litigation is a 2018 Washington Post article (signed by Heard but actually written and pitched by the American Civil Liberties Union) which portrays Heard as an abused woman speaking out but doesn’t directly name Depp as her abuser.

Given that Heard had previously accused him of abuse, no one could fail to make the link; but there is still the question of whether such an indirect statement can be seen as defamatory. But for a lot of people commentating on this story, it’s not so much about the First Amendment as it is about #MeToo and #BelieveWomen.

A lot of the public response has favored Depp (partly because he has armies of mostly female fans!), and feminist pundits are dismayed. At Vox, Aja Romano laments that a cultural takeover by Depp acolytes” may have “created a seismic value shift,” marginalizing victims and even “destroying years of progress made against domestic abuse in the US.” On the New York Times opinion page, Michelle Goldberg laments that Heard is the target of a “#MeToo backlash” and of “industrial-scale bullying,” while Jessica Bennett speculates that it’s really all about the misogynist thrill of watching a woman get publicly humiliated. Jessica Winter also focuses on Heard’s gleeful public trashing in the New Yorker.

What’s interesting is that all these Heard defenders acknowledge that there are real problems with her claims. Romano grudgingly concedes that “it’s impossible to completely absolve Amber Heard, who has her own alleged history of violence” (toward a former girlfriend). Goldberg also notes that “Heard has admitted hitting Depp, and has been recorded insulting and belittling him,” and that their marital counselor says there was “mutual abuse” in their relationship. Winter notes that Heard has “made questionable statements” (some of her claims of beatings that left her with black eyes are contradicted by contemporaneous photo and video evidence) and that some of her recorded conversations with Depp produced as evidence of her own abusive behavior are indeed disturbing. But apparently (according to the pro-Heard pundits) all this merely makes Heard “an imperfect victim.”

Wait up. “Imperfect victim” means more like, say, “battered wife, but also a shoplifter.” This is more like “mutual combatant” and “unreliable witness.”

Goldberg writes:

Some domestic violence experts consider mutual abuse a myth, arguing that while both partners in a toxic relationship can behave terribly, one usually exercises power over the other. But even if you believe that Heard acted inexcusably, the idea that she was the primary aggressor—against a larger man with far more resources who was recorded cursing at her for daring to speak in an “authoritative” way—defies logic.

But her link on “myth” leads to the webpage of an advocacy group, the National Domestic Violence Hotline, that doesn’t quote any experts and has only assertions by an anonymous author. There is actually a large body of research supporting the view that a lot of domestic abuse involves mutual violence or female aggression and that, while women are more at risk of injury, men are hardly immune. (The gap in strength can be neutralized by impromptu weapons, or by the normal male conditioning—in our culture, at least—not to use force against a woman.) Depp may have had more resources as a big star, but Heard had societal biases on her side; in one justly infamous recorded conversation, she taunts Depp:

You can please tell people that it was a fair fight, and see what the jury and judge thinks. Tell the world Johnny, tell them Johnny Depp, I Johnny Depp, a man, I’m a victim too of domestic violence. And I, you know, it’s a fair fight. And see how many people believe or side with you.

Basically, we’re being asked to support Heard because she’s a woman. But that’s not the way it should work. Yes, of course it’s appropriate to take physical differences between the sexes into account when considering the seriousness of a domestic violence case. But sex and physical strength are just two of many factors.

As for Heard’s trashing in the court of public opinion: Depp was roundly trashed in the media when Heard first made allegations against him in 2016. The Atlantic noted that “his public profile has collapsed” due to the accusations. Depp’s casting in the Harry Potter prequel, Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald—and later in Fantastic Beasts 2—set off a chorus of outrage; there were such headlines as, “Everyone But Hollywood Agrees Johnny Depp Shouldn’t Be In ‘Fantastic Beasts’” (HuffPost), “The ‘Fantastic Beasts 2’ Problem: Why Is Hollywood Giving Johnny Depp a Pass?” (the Daily Beast), and “Why Is Johnny Depp Still Employed, You Ask?” (the Mary Sue). Heard’s champions lament the lack of empathy for her in the midst of the backlash; but in this case, it seems that empathy should be a two-way street.

However the case turns out, it has spotlighted the complexities of domestic violence. That’s a good thing.

The claim that gun regulations won't "rid us of mass shootings" is the biggest straw man in recorded history. Of course they won't. How about reducing them? You think that might happen? You think regulations might stop, or at least delay for a few days while a kid with an immediate reaction to a bad family situation, might prevent a kid from going nuts with a gun? Or that if it doesn't, you could reduce the kills by banning high-capacity magazines? Second biggest straw man: Dems ignore the legit needs of gun owners for "protection." From what--burglars? You need an AR-15 with a high-capacity magazine for that? The people who want to keep these unregulated weapons want them for a fever dream of rebellion--Exhibit A is Mo Brooks on Fox this morning: "we need guns to protect us from a dictatorial government." When Mo's hoped-for apocalypse comes, who's going to be more authoritarian, Joe Biden or the Proud Boys and the Three Percenters? Trust me, they will have no use whatsoever for empty suits like Mo Brooks.

The bothsideism in this article is inaccurate and disingenuous.

No credible Democrat or liberal suggests that instituting reasonable gun regulation will eliminate all mass shootings. And the discourse on the Democratic side is anything but "oversimplified". Detailed studies giving rise to specific regulatory frameworks (like the Assault Weapons Ban of 1994 and the Brady Bill, both of which had the desired effect of reducing gun violence) comes from Democrats.

But what do we get from Republicans? Less doors in schools (!!). Arm the teachers (!!!). More God and Christian prayer in the schools (!!!). It's utter stupidity and obscures what we need to do. Republicans sometimes mention addressing mental health issues, funding for which they NEVER vote for, or eliminate in their state budgets (see: Greg Abbott). You've posted a Christmas photograph of Thomas Massie and his heavily armed wife and children - if that isn't a picture of mental illness that gives rise to violence, I don't know what is.

In 1988, one metal dart killed one child, and metal darts were eliminated. No child has died from a metal dart since. That should tell us how far we've fallen down the gun culture rabbit hole since. It's my opinion that the 2nd Amendment is not absolute, as Scalia said - we must, in the public interest, restrict and regulate guns. But, somehow, at the same time, must break the raging ugly fever of the sick gun obsession that pervades and is overtaking our nation. We're on the precipice of becoming a failed nation. That's not an "oversimplification". It's reality.