China Could Be More Aggressive Post-Growth

Without a rising standard of living to offer its people, and with its window of opportunity shrinking, the Chinese Communist Party may look to expansion to legitimate itself.

CHINA’S ECONOMY IS FACING A SLOWDOWN—all the headlines are saying it. Most Americans, who increasingly see China as a threatening rival, might welcome news that China seems to be losing steam. However, the short-run implications of China’s downturn may prove anything but welcome.

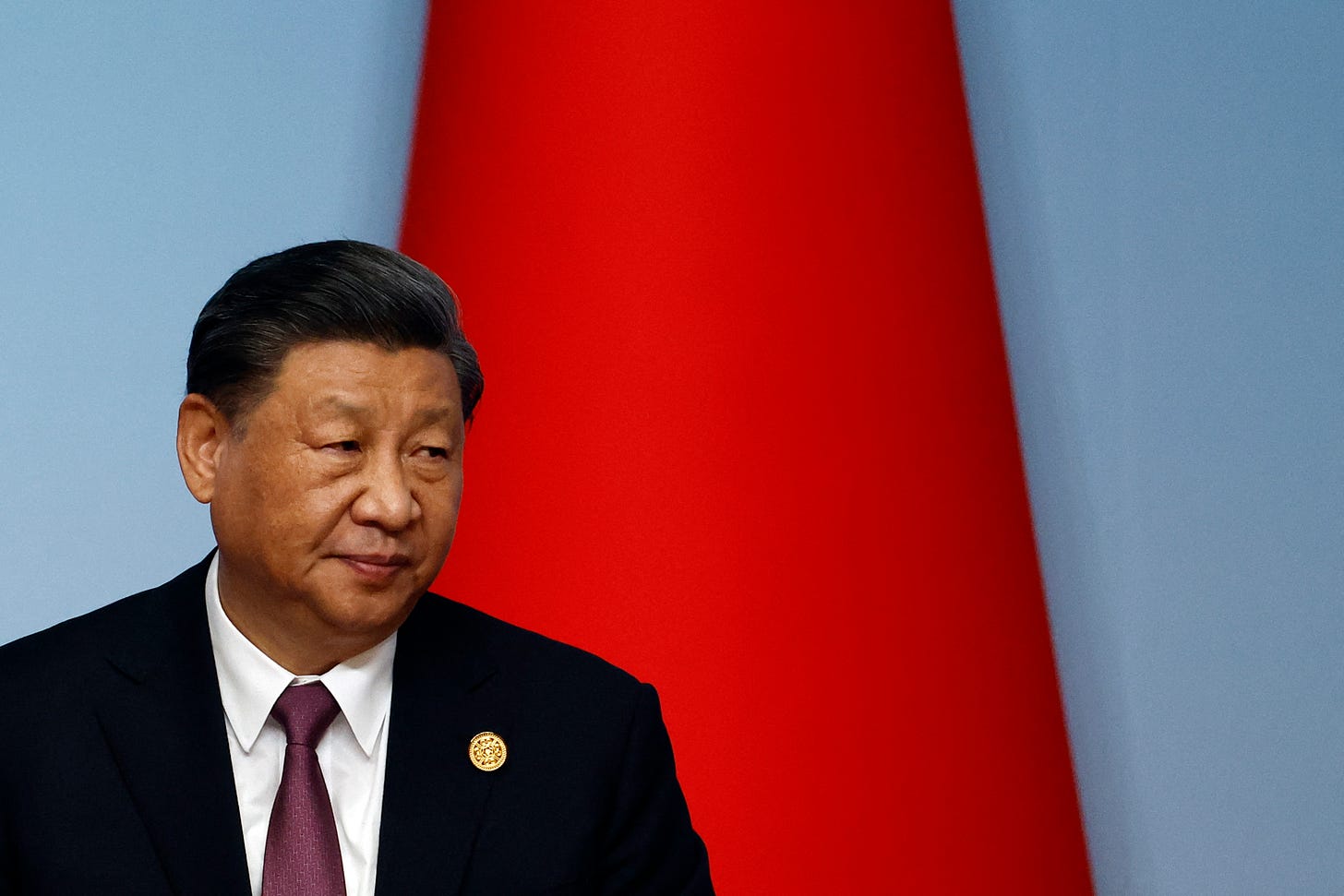

How this plays out depends, to a large extent, on how China’s leaders respond and what choices they make. China’s challenges could be seized as an opportunity to reorient its economy, and its international relationships, in a more productive direction. But given Xi Jinping’s track record, this seems unlikely.

China’s economic miracle rested on two pillars. The first was reform. Starting in the 1980s, and accelerating in the 1990s, China opened its doors to foreign investment, privatized vast chunks of its state-run economy, and allowed people the freedom to start businesses, own homes, choose their own jobs, and study and travel abroad. In doing so, it unlocked the potential of 1.4 billion people who wanted to improve their lives.

The second pillar was exports. A poor country has relatively weak domestic buying power, which makes it difficult to justify investments to build up supply. By turning to foreign markets that can afford to consume, China turbocharged investment and developed much more rapidly. This “export-led growth model” has lifted several Asian countries out of poverty, but it relies on an imbalance: If one country produces more than it consumes, someone else must consume more than they produce. Starting in 2008, the ability of the rest of the world to go into greater and greater debt to consume everything China produced started to flag. As the world’s second-largest economy, China had outgrown the export-led model.

During the 2008 financial crisis, China’s export economy suffered a severe shock. China’s leaders might have tempered investment in favor of domestic consumption at the price of a slower but more sustainable growth rate. Instead, they chose a different path. They opened the spigots of credit from state-owned banks and doubled down on investment as a replacement for external demand. Even as it outgrew the export-led growth model, China locked in the turbocharged levels of investment that only that model could support. They built steel mills to produce steel to build more steel mills. They built huge swathes of luxury condo high-rises that buyers could only afford because they expected prices to keep going up. They built world-beating industries, like solar panel manufacturing, that couldn’t break even amid the glut they had created. And when losses piled up, China’s bureaucrats pretended they didn’t exist by rolling over bad loans indefinitely within the state banking system and quietly bailing out the exceptions when they blew up.

China’s leaders have known for a while that they have a problem. Soon after Xi first took office in 2013, the Chinese Communist Party published the Third Plenum Document, which promised a slew of what were described, even then, as long-overdue reforms to instill market discipline, especially through the financial system, and rebalance the economy toward domestic consumption. “The market,” it intoned, “must be decisive.” But that was the rub: If the market was to be decisive, the Party could not be. Xi chose the Party, and the reforms were pushed back. Year after year, Chinese officials promised that once Xi had a firm handle on the country’s politics, the economic reforms could then move forward. But by the time Xi spurned traditional term limits and made himself president-for-life last year, they gave up the charade. Far from loosening the state’s hold over the economy, he moved to solidify it, going after entrepreneurs who, in his eyes, seemed to threaten the Party’s monopoly on power. The trade war with Trump shifted Xi’s strategic focus towards insulating China from the influence of foreign investors and trading partners. The COVID-19 pandemic effectively closed China’s borders for almost three years, driving this trend towards isolation and control even further.

Initially, many hoped that the lifting of China’s COVID restrictions might signal a change in fortune. Chinese officials mouthed reassuring words about the welcome importance of entrepreneurship, foreign investment, and trade. Since then, a deepening sense of gloom has taken hold—both outside and inside of China—that the country’s problems won’t be that easy to overcome, and that under Xi, it’s headed in the wrong direction.

If China did reform and rebalance its economy, the outcome could be a win-win. Since China has produced more than it consumed for many years, it has accumulated the foreign exchange reserves that could allow it to consume more than it produces—i.e., run a trade deficit. That would help cushion Chinese consumers from an otherwise wrenching economic adjustment, while reducing trade tensions and turning Chinese demand into a driver of global growth. Loosening the government’s political hold on the economy could unlock productivity gains in “softer” sectors—agriculture, logistics, services, health care—that have been deprived of resources amid China’s state-backed investment boom.

But the prospect of China pursuing this path is increasingly unlikely. Turning China’s existing economic model upside-down is anathema to conventional wisdom, and Xi appears to see giving up any control at all as a threat to the Party’s power. And if things don’t improve, in one way or another, the funds that China could use as a cushion may eventually find another way to leave the country—capital flight.

If, on the other hand, China continues to resist rebalancing, it could harm more than its own economy. Already, some would argue that Xi’s “Belt and Road Initiative” has merely served to shift China’s investment binge abroad, entangling other countries in a net of expensive, money-losing projects. A major reason they lose money is that what the world needs from China is demand for its products, not more Chinese-funded supply. As China’s slowdown deepens, there will be a strong temptation to devalue its currency in an effort to boost exports. Some economists familiar with crises in heavily indebted deficit countries will endorse this approach, failing to realize that it is exactly the wrong medicine for a chronic-surplus, creditor country like China. A weaker Chinese currency will only undercut the purchasing power of China’s consumers, deepen global imbalances, and turn China into a drag on other countries’ growth—including our own.

The other danger isn’t economic, but geopolitical. For years, U.S. policymakers have focused on the challenges and potential threats posed by a strong, prosperous China. But countries that think the world is their oyster, whatever their ambitions, tend to be risk-averse—after all, as they see it, time is on their side. By contrast, countries that see their dreams of greatness in unexpected danger become desperate, willing to take sometimes reckless risks to preserve their command of the situation. That’s what happened in 1941, when Japan, bogged down in its invasion of China, faced a U.S. embargo on oil and steel critical to its war effort. It’s also what happened after 9/11, when the United States began to see outsized risks around every corner.

The popular authority of China’s Communist Party has long rested on its ability to deliver on twin promises: a better life (in purely economic terms) and a strong and unified China, in contrast to the “century of humiliation” the country experienced from the Opium Wars to the Revolution. If it loses the former, it will have to rely more heavily on the latter. The forcible reunification of Taiwan would be the ultimate feather in Xi’s cap, in this respect—albeit at grave risk. A China faced with economic disappointment, increasingly distrusted by investors and trading partners, might be more willing to take that risk. Such a move could bring the United States into direct military conflict with China. Whatever the outcome, the implications would be tragic and far-reaching.

A few years ago, I was at a gathering of economists and China-watchers in Washington, D.C. We were discussing the prospect of China facing serious economic difficulties ahead—a likelihood we could already anticipate. I asked the group, “In the past, the goal of U.S. policy would have been to do what it could to reduce the prospect of an economic crisis in China, and mitigate the damage. Is this still the case, or is our object now to increase the likelihood of such a crisis, and exacerbate the damage?” The participants shuffled awkwardly in their chairs and greeted the question with silence. Afterwards, a prominent American policymaker came up to me and confided, “You know the answer: It’s the latter.” We should be careful what we wish for.

Patrick Chovanec is an economist in New York who has taught on U.S.-China relations at Tsinghua University in Beijing and Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.