The Clashes at ‘National Review’ Before Conservatives Took Over the Republican Party

What the magazine’s early internal fights over endorsing presidential candidates can teach us about politics vs. principle.

HOW SHOULD PRINCIPLED CONSERVATIVES, committed to conservative ideals and their realization, relate to the grubby political world and the demands of winning votes and making necessary compromises? Today the dilemma is an acute one. But it’s not new. Ever since conservatism in the United States first emerged as a conscious movement, its leading activists and intellectuals have struggled with this question, especially regarding their relationship with conservatism’s imperfect political vessel, the Republican party. Presidential elections are particular flashpoints; during these quadrennial clashes, the imperatives of ideological purity are brought into direct conflict with political and electoral realities. This dynamic played out starkly and articulately at National Review during its first decade, in behind-the-scenes debates about whether the flagship conservative magazine should endorse the GOP’s presidential nominees.

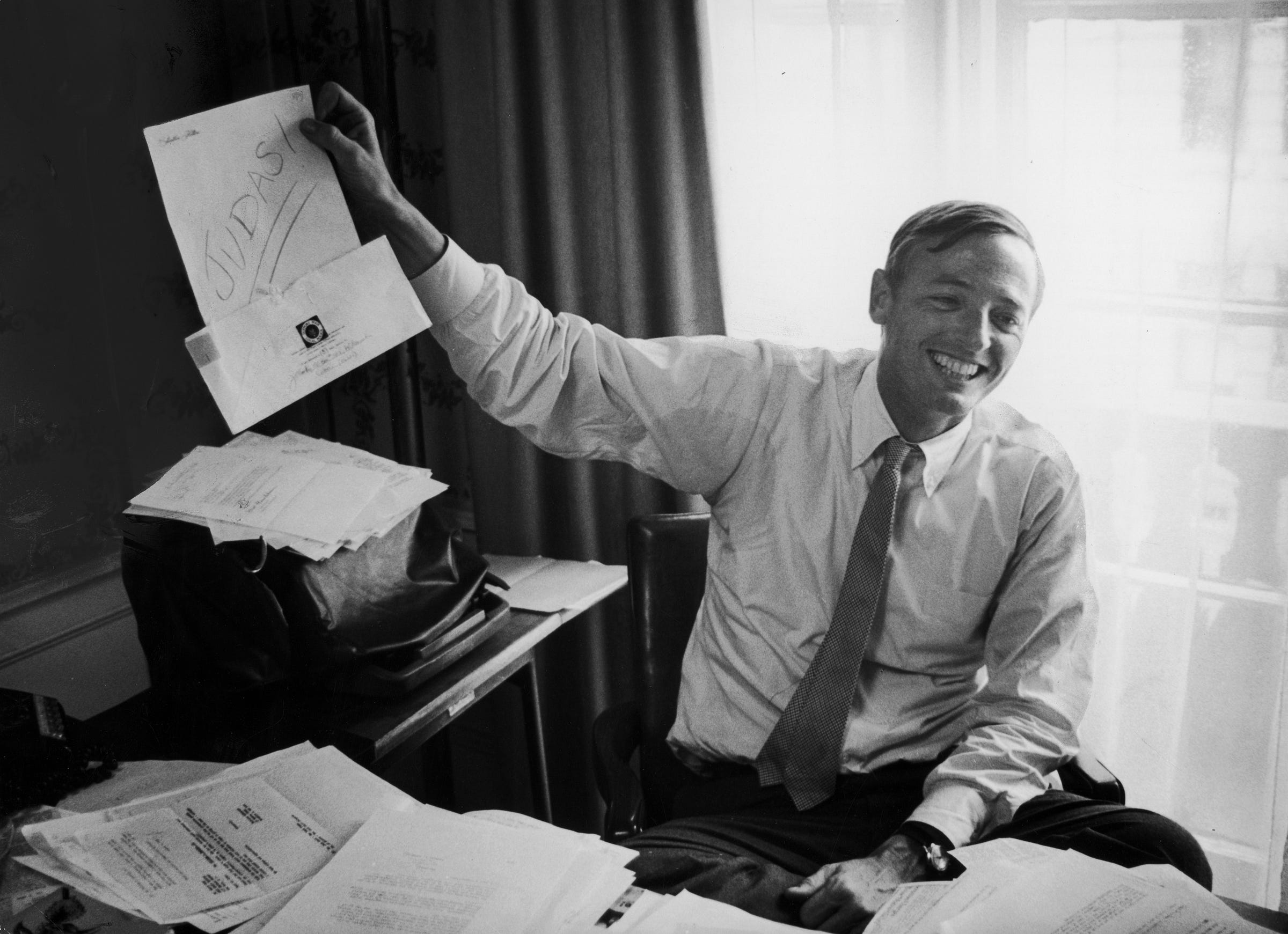

Founded in late 1955 by editor-in-chief William F. Buckley Jr. and several confreres and supporters, National Review was intended to be an intellectual beachhead for conservatism. With ambitions far beyond the world of journals, though, Buckley and NR’s editorial staff strategically sought to use their magazine to advance conservatism as a viable political force. While somewhat dilettantish at first, as the premier spokespeople for ideological conservatism the National Review circle felt their decisions on the selection of stories, framing their editorial line, the tenor of the magazine, and their endorsements were all freighted with political resonance.

In the 1956, 1960, and 1964 presidential elections, National Review’s editorial staff debated whether and how to endorse the candidacies of Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Barry Goldwater. Eventually, the so-called Buckley Rule emerged—support for the “most rightward electable candidate”—but in NR’s early years, disputatious voices among the editors argued in favor of the need to win journalistic cut-through, maintain ideological purity, stay within touching distance of political power, and avoid linking the prospects of conservatism too greatly with losing candidates. These aims are obviously in tension.

The internal disputes at NR illuminate the dynamics of the conservative movement and its persistent challenge of positioning itself in relation to politicians. In what follows, I’ll examine those debates—reconstructing them not only from what appeared in the pages of NR but from correspondence and interoffice memos, collected in three separate archival collections, that reveal the rationale and motives behind these decisions and how these conservatives saw themselves and the GOP.

The ownership structure of National Review and Bill Buckley’s own roles as its face and (to some extent) as the gatekeeper of “respectable conservatism” made him an absolute monarch at the magazine. He ruled—generally benevolently—over a boisterous and opinionated gang of editors whose peccadilloes and ideological leanings reflected some of the nascent strains within conservatism.

Buckley was, however, often an absentee monarch, especially after the magazine’s first couple of years. He had a whirlwind personal and professional schedule, and every year took a long skiing-cum-writing retreat to Gstaad. The mountains are high and the emperor was far away, so NR’s big personalities found reason to fight with one another over the direction of the magazine and, perhaps grandiosely, conservatism itself. In the struggle, senior editor James Burnham proved a dominant personality. A generation older than Buckley and a serious if extreme intellectual in his own right, Burnham was the éminence grise of National Review. He was both Buckley’s mentor and his trusted adjutant. A second key actor was the magazine’s publisher, William Rusher. Much more of an active pol than Burnham, Rusher analyzed the Republican party cynically and would play an important part in the party’s drift toward polarization. Rounding out the leading cast was the editor of the magazine’s Books, Arts, and Manners section, Frank Meyer. Most remembered today as the architect of “fusionism”—the consensus conservative outlook that presaged the “three-legged stool” of Reaganism—Meyer thought consciously about how to advance the prospects of conservatism.

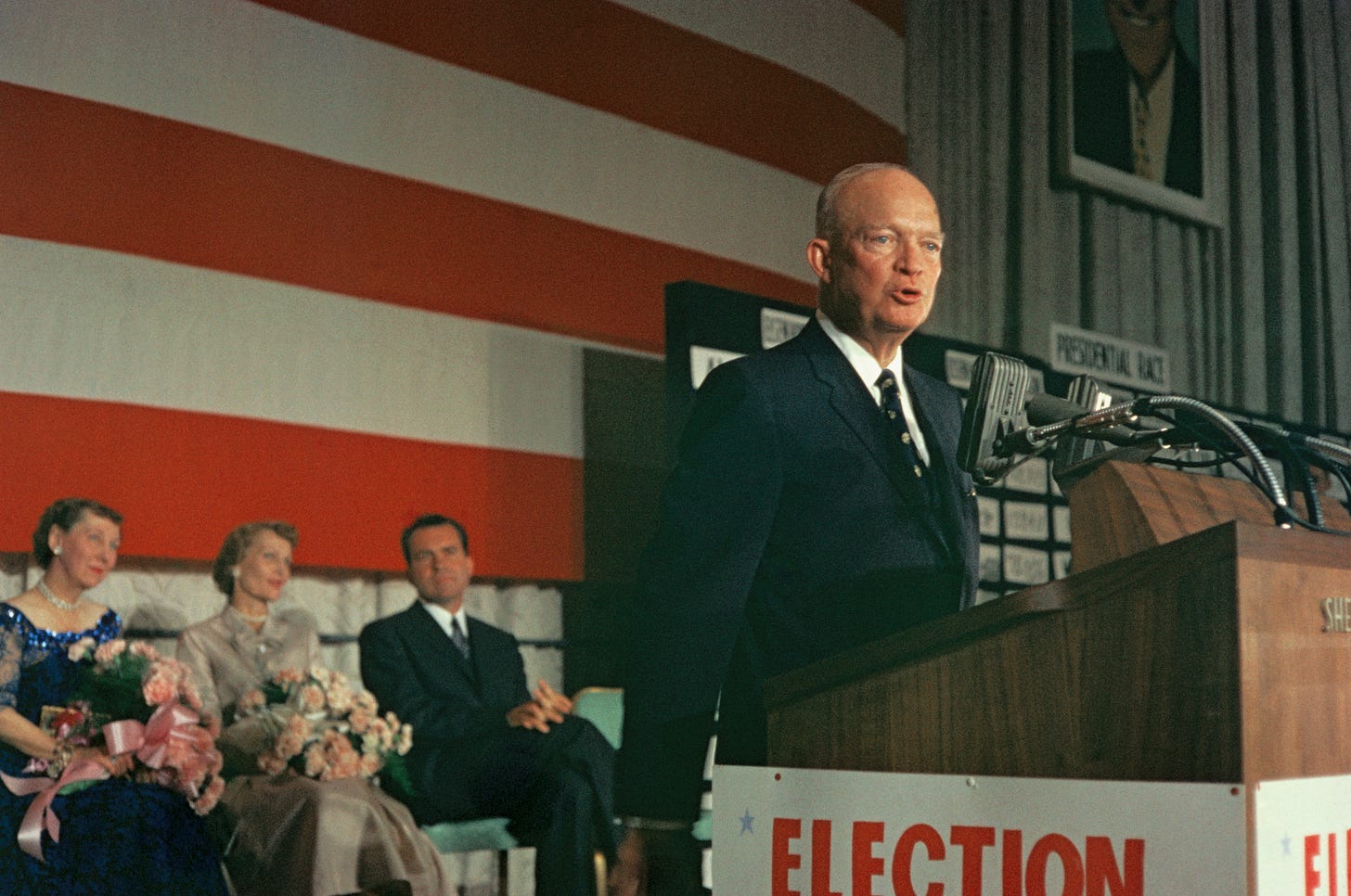

1956: I prefer Ike

IN SOME RESPECTS, movement conservatism and National Review’s earliest motivation was to oppose the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower. After the New Deal and twenty years of Democratic ascendency, how was it that the best the right could manage was Ike’s perceived standpattism and his Eastern allies’ “Modern Republicanism”? National Review would offer a much sterner alternative.

On September 23, 1955, shortly before National Review’s launch, Eisenhower suffered a serious heart attack. Indulging his habit of overconfident predictions, Burnham espied an opportunity to launch the magazine with a splash. “Ought National Review, in its very first issue, announce its support of [right-wing California Senator William] Knowland for President?,” Burnham wrote in a letter to Buckley. The move would be journalistically “sensational.” While he saw a headline-grabbing controversy here, in general, Burnham counseled NR to be realistic and endorse moderate Republican candidates. Even this harebrained scheme he sold as deferential to the world as it was. Sure, Knowland was unimpressive, Burnham acknowledged. “But we are dealing here with political realities, not mere abstract analysis.” Assuming Eisenhower is out, no other serious conservative candidate presented themselves.

Burnham pushed the endorsement idea, but his colleagues let him down gently. At the time, Buckley had been wooing the ex-spy and writer Whittaker Chambers to join the magazine; his 1952 memoir Witness had been a bestseller. Chambers considered talk of a Knowland endorsement right-wing escapism. While a radical counterrevolutionary in his intellectual life, Chambers liked Vice President Richard Nixon—his ally in the Alger Hiss case—and thought right-wing politics needed to make peace with existing structures to be meaningful. He conveyed those concerns to Buckley. So, while Burnham, Buckley, and another NR co-founder, the combustible Austrian émigré Willi Schlamm, all agreed on Knowland as the best option available if Eisenhower were to exit the stage, Buckley, perhaps influenced by Chambers, and Schlamm felt endorsing Knowland would give the impression their new magazine was merely a tool of factional Republican politics rather than a serious journal in its own right.

But Eisenhower did not drop out, so the Knowland matter became moot. Burnham, although an arch-hawk critic of Eisenhower’s foreign policy, reconciled himself to political reality, attending the 1956 Republican National Convention and voting for Eisenhower’s nomination. With Ike now on the ticket, the question for NR became “Should conservatives vote for Eisenhower-Nixon?” Reflecting the division in the editorial office, National Review split the difference. They published competing answers and a reader symposium.

Burnham made the affirmative case, using the effective logic of a united front against the left. The nature of American party politics, he argued, meant all presidential candidates were compromise candidates. You have to support the one who most advances your long-term goals; anything else is “sectarian” and only fuels the impression that conservatives are extremists outside the mainstream. All things considered, the Republican party performed better on domestic and foreign policy than the Democrats. Some of Burnham’s assessment was negative polarization: the “key units of the anti-conservative forces”—namely leftist intellectuals, the “labor bureaucracy,” and the Communist Party—all favored Adlai Stevenson. In any case, Burnham wrote, “is it not pharisaic, as well as stultifying, to adopt a holier-than-thou attitude of petulant withdrawal that by implication dismisses [conservative Republican politicians] as turncoats?”

There had been some enthusiasm for a third-party candidacy among conservatives. Burnham saw no hope for it. What’s more, even within a third party, “the genuine conservatives within it would be a minority.” In 1956, the energy for a third party came from the Jim Crow South. There were “true conservatives but also not a few plain racists masquerading as conservatives,” plus, Burnham added, “all sorts of cranks and anti-Semites would inevitably flock around.”

Notably, Burnham’s case for a big-tent, united right led him to argue repeatedly that conservatives should court the center. Burnham was particularly susceptible to arguments that conformed to the dynamics of reality—but within the borders of National Review, that meant he was, on this and other domestic issues, something of a left-deviationist. The larger point is that, throughout these internal discussions, all sides were determined to maintain their distance from cranks and racists.

Making the case against Eisenhower was Willi Schlamm, who rejected the idea that Ike represented the lesser of two evils. Far better to have an effective Republican opposition than a liberal Republican in office. “Dwight Eisenhower, an inconsistent Liberal, is in firm control of the Republican Party,” Schlamm wrote. “For conservatives, the strategic job in this year’s election is to break that control. It can be broken only by defeating Mr. Eisenhower.” If hampered by an effective opposition, a Stevenson presidency would hardly be worse than an Eisenhower one, but would create the conditions for an authentic conservative GOP. Even so, that didn’t mean Schlamm would affirmatively vote for Stevenson; he preferred to sit out the presidential vote altogether.

Reader letters reflected this range of opinion. Among the writers, the 30-year-old Willis Carto—who would later found the anti-Communist group Liberty Lobby, then become notorious for his antisemitism and Holocaust denial—reiterated Schlamm’s point. “I believe it would be a tragedy for America if Eisenhower was re-elected. . . . Therefore, my suggestion is: vote for Stevenson. And concentrate on your local Congressman this fall.” Meanwhile, the anarchocapitalist economist Murray Rothbard proposed a negative voting system by which voters could deny politicians a popular mandate.

It’s fair to say National Review and its readers were frustrated by their choices in ’56. For his part, Bill Buckley suggested boycotting the election entirely, which he did.

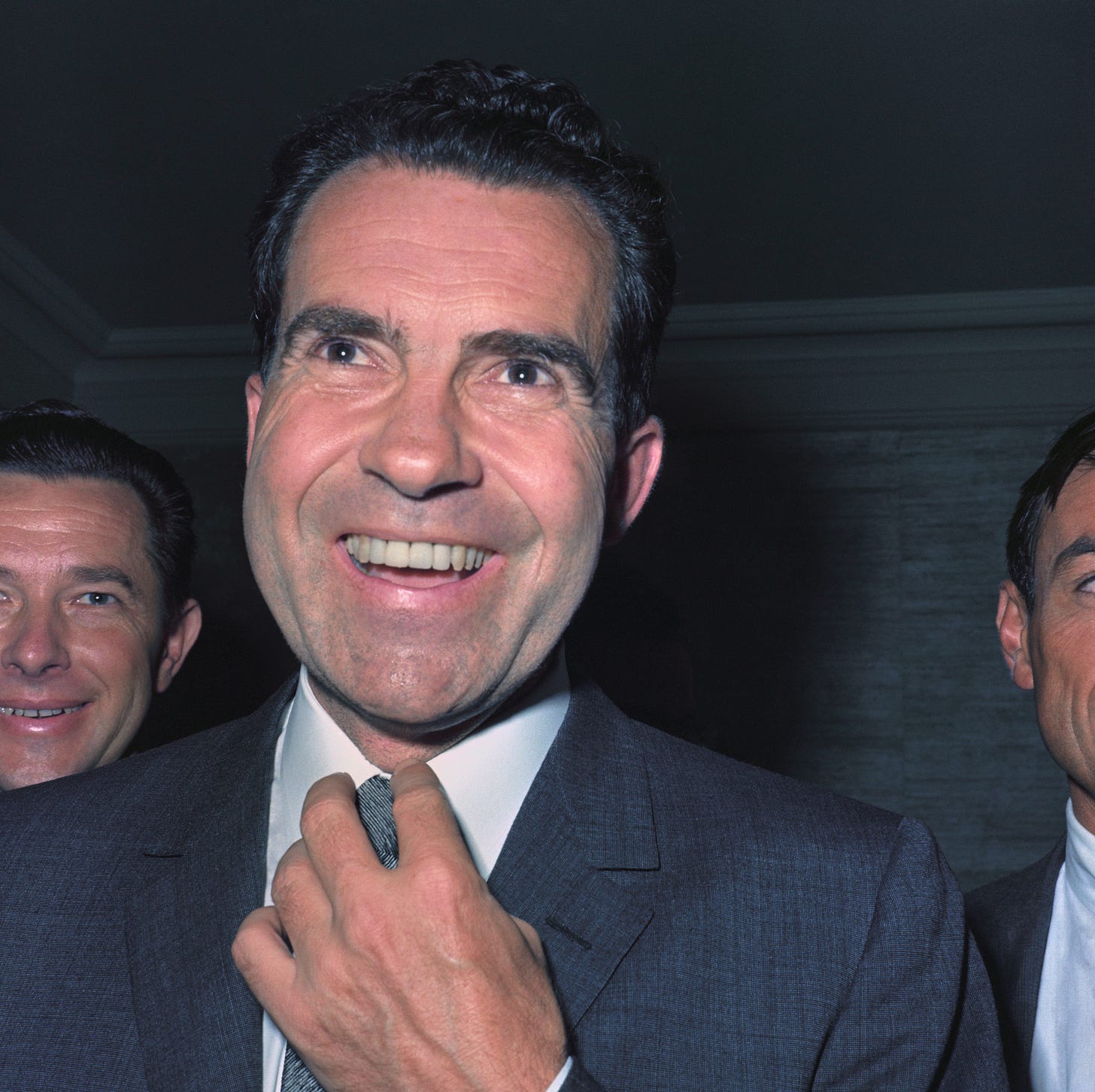

1960: Nixon now?

DESPITE HIS REPUTATION for toughness on communism and red-baiting, the conservative right was lukewarm at best on Richard Nixon. He bore the taint of Ike’s administration, even though Eisenhower had given Nixon humiliatingly little to do. And despite his grievances toward the establishment, Nixon had not himself risen up within the conservative movement or its precursors. Conservatives fundamentally did not trust Nixon to be anything more than another moderate Republican.

In 1960, several countervailing dynamics were at play. Under no circumstances could conservatives let the liberal Nelson Rockefeller win the nomination. As Murray Rothbard wrote to Buckley in late 1959, regardless of what they would do in the actual election, it was “incumbent” on conservatives who are registered as Republicans “to bend every effort to nominate Nixon over the clearly more socialistic Rockefeller.” At the same time, since the last election Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater had emerged as a far more credible conservative champion than Bill Knowland. Was there any possibility he might be an outside candidate for the nomination?

In a memo to key staff, National Review’s resident ideologue, Frank Meyer, laid out the stakes. Conservative leadership—by which Meyer meant NR, “undoubtedly the center of the movement”—must maintain its independence, “uncompromised by association with the Establishment.” Therefore, under no circumstance could NR “endorse Nixon” or Rockefeller. As Schlamm had argued in 1956, Meyer insisted the election of a liberal Republican president would stifle the development of a conservative opposition. However, now Goldwater gave conservatives political expression in a manner unimaginable in 1956. So, Meyer proposed, between now and the conventions, NR should “take the position that Goldwater is the only candidate whom conservatives can support; and that between the convention and the election we criticize both candidates on the basis of the standard we have established in the weeks before the conventions.”

Meyer probably made the case so starkly because, as he confided in a letter to Willmoore Kendall, he felt Burnham to be “more or less insidiously” exerting pressure on the magazine to support Nixon. Buckley, he reported, “as so often, is wavering.” As a case in point, Meyer, as books editor, had asked Burnham to review Goldwater’s 1960 manifesto, The Conscience of a Conservative, ghostwritten by an NR associate. While on vacation, Burnham made a last-minute decision that Conscience did not deserve a full review; an editorial about it would suffice. Incensed, Meyer reviewed it himself. “Everything would indicate this was an effort to downgrade any right-wing opposition to Nixon,” Meyer alleged, perhaps jumping at ghosts. At this stage, Meyer resented Burnham personally and considered him a “non-conservative influence at the heart” of National Review.

Siding with Meyer was Bill Rusher, the magazine’s pugnacious publisher, who had once had his heart broken by Eisenhower. Since then, he had maintained a love/hate relationship with the GOP, feeling as if he were in a constant struggle to replace it or shape it to his will. Early in 1960, he argued NR gained nothing by endorsing Nixon, although he acknowledged his position was “unqualifiedly ‘revolutionary,’ and that undoubtedly colors my attitude” to the issue.

Nearly everyone else at the magazine joined Meyer and Rusher in opposing support for Nixon. Almost alone in the other camp were Burnham and his reliable confederate Priscilla Buckley, the magazine’s managing editor and Buckley’s sister.

In reality, Burnham’s preference for Nixon was halfhearted. Much to the disgust of the other members of the NR circle, Burnham actively preferred Rockefeller. “I have so little personal enthusiasm for Nixon that I may not be able to endure voting for him,” Burnham admitted to Buckley in a letter. “Nevertheless, I am more than ever convinced that the public, objective conservative position in this election is and must be, Vote Nixon,” he wrote in his “11+ hour” effort to sway Buckley. For NR to withhold its support was “improper,” a form of “inverted radicalism.” He repeated his argument from 1956—that those whom conservatives oppose were supporting the Democratic candidate—using, in this private correspondence, some striking language:

the disintegrative leftist ideologues, including those who ruin educational systems; the most dangerous and ruthless of the trade union bureaucracy; the appeasers and collaborationists; the most extreme secularists (ironically enough!), including the most Jewish Jews; the city lumpenproletariat; the socialists, fellow-travelers and communists; and—one might add—the appeasers, socialists and collaborators of the entire world as well as this country.

As yet, he concluded, there was no alternative; “a conservative has to set his course within the frame of reality.” Only radicals leave reality for a “private dream.” Buckley’s sister quietly agreed, suggesting NR support Nixon on anti-appeasement grounds.

This line of reasoning for supporting Nixon left Rusher unimpressed; it could equally be applied to every Republican candidate ever, no matter how unconservative. If that was to be NR’s position, he didn’t want to pretend Nixon was “a particularly toothsome Republican, or Kennedy a uniquely malignant Democrat.” Once again, conservatives must refuse to support Nixon as a first step in taking over—or breaking away from—the party altogether. Voting for Nixon just strengthens his hold on the GOP.

Some at the magazine took Rusher’s argument further. Staffer Neil McCaffrey, who a few years later would go on to found the Conservative Book Club, wrote to Buckley, Rusher, and Meyer to suggest that by denying Nixon, “a vote for Kennedy is a vote for Goldwater.” Conservatives must take one step backward before going forward: If they were to win control of the GOP, the party under Nixon must lose in 1960. Unlike Rusher, though, McCaffrey believed the Republican party to be the only viable pathway to power. A third party would be dominated by “the lunatic fringe.” Could the lunatic fringe “attract any respectable support in this country? For that matter, is it desirable that they attract such support?”

The call rested with Buckley. While he did not want NR to have a “monastic function of bead-saying in isolation from the rest of the world,” he concluded “we actually increase our leverage on events by failing to join the parade.” It would be enough for NR to criticize Kennedy and outline their thinking to their readers. Buckley hoped Burnham would find this satisfying even if “lacking in intellectual rigor.”

In the end, unable or unwilling to definitively pick a side, Buckley restated NR’s arguments from 1956. It was defensible for conservatives to vote either for or against Nixon. “National Review was not founded to make practical politics.” They were thinkers, mediators, and “tablet keepers.” “Our job today is surely to remind ardent members of the conservative community that equally well-instructed persons can differ on matters of political tactic, and that it is profoundly wrong for one faction to anathematize the other over such differences.”

1964: Going down with Goldwater

THINGS HAD CHANGED BY 1964. In part as a result of party machinations Rusher had been involved with, rock-ribbed conservative Barry Goldwater had won his party’s presidential nomination. His selection removed one question; of course National Review would support him. But it was unclear what support meant for an ultimately journalistic endeavor, especially as Goldwater’s chances of success vanished toward zero.

As early as mid-1963, Burnham—yet again—advised tacking to the center. In the election, Goldwater would need to avoid the already creeping perception he was “captive of the extreme Right” by making “inroads into the moderates and the Center,” Burnham wrote in a letter to Buckley. The extreme right, and not just the paranoid John Birch Society, turned off the average voter. Instead, Goldwater should take the right flank for granted and woo the middle. Some of Burnham’s push for moderation may have reflected his greater comfort with the Eastern establishment. A sophisticate and, frankly, part of the elite, the Princeton- and Oxford-educated Burnham had a snobbish side that drew him to Buckley but led him to look down on the artless striver Nixon and arriviste jock Goldwater.

When Goldwater’s nomination campaign took shape in earnest, under the pall of the Kennedy assassination, Rusher took it as read that “National Review is for Goldwater.” Certainly, being for him meant publishing news about Goldwater, good and bad, but it also meant boosting him as their preferred candidate. An editorial in the magazine laid out NR’s approach. They would be “enthusiastic endorsers of Mr. Goldwater’s candidacy”; “independent evaluators of his statements and his campaign”; and “objective analysts of his chances.” Rusher detected a “potentially dangerous ambiguity” in this formulation, especially if it was to guide NR editorial policy while Buckley was absent—that is to say, when Burnham held the reins. What did objectivity mean when liberals controlled the “almost uniformly hostile press”? National Review should report the facts, but also offer critical analysis of unfavorable facts when it was being deliberately ignored.

In February 1964, Rusher and Burnham met in New York to hash it out. Goldwater doesn’t acknowledge NR, but “we have been servile to him,” Burnham complained. With an old propagandist’s attention to a potential controversy, he suggested it would be more notable for NR to criticize Goldwater. And where Burnham wanted to avoid going down with Goldwater, the purist Rusher thought there was nothing “dishonorable about losing in a good cause.” Rusher thought they had reached agreement. But two weeks later Burnham wrote to Buckley emphasizing the need for NR to demonstrate its independence. “I don’t think we have always sustained this rather delicately balanced posture,” he wrote. “The fact is, as we know, that Goldwater is a second-rate person; and he seems to be surrounded by third- and fourth-rate persons,” Burnham continued. Perhaps NR could offer more policy and tactical criticism of the campaign. Of course, he added carefully, Buckley would need to write the editorial himself for reasons of office politics.

While on spring vacation in Arizona, Burnham wrote a column calling Goldwater a regional rather than national candidate, and offering unsolicited campaign advice. Apoplectic, Rusher complained to the boss about the “Senior Editors” conducting “systematic bombardments of key editorial policies of the magazine from the privileged sanctuary of their by-lined column.”

By June, though, Rusher had come around to the need to avoid tarnishing NR’s journalistic reputation by overstating Goldwater’s chances of beating Lyndon Johnson in November. National Review should acknowledge but not belabor this point—and leave open the possibility of victory to avoid conservative hopelessness. For his part, Meyer, like a good number of other conservative intellectuals, still thought Goldwater had a chance of winning and in a column in a special double issue in July Meyer lauded the candidate’s “solid strength in the Midwest, the Mountain States, and the Southwest,” plus his ability to carry the South. (Meyer proved right about the Deep South, wrong about everywhere else.) By September, Buckley, grieving the sudden death of his younger sister Maureen, induced gasps at a Young Americans for Freedom event with an off-the-record speech called “The Impending Defeat of Barry Goldwater.”

Even if Buckley and others at the magazine anticipated Goldwater’s defeat, his candidacy had tremendous symbolic value for the conservatives at National Review. “An attempted prison break,” Buckley called it. In the same July issue in which Meyer boosted Goldwater’s chances, NR published a series of long essays outlining a vision of a Goldwater administration. On Election Day, Rusher circulated a memo to get ahead of the likely aftermath of an LBJ landslide. There was value in the crusade, he argued. Goldwater “forcibly” stated the conservative case. The conservative movement trained and “blooded” activists across the country. They forced the liberal establishment to demonstrate its full, undivided strength, which proved to be less than feared. And they won concessions from liberal positions. “Goldwater’s nomination was the first—not the last—battle of resurgent conservatism,” Rusher intoned. “There will be others.”

The size of LBJ’s victory and the scale of the Great Society, though, changed something for Buckley. This wasn’t Eisenhower/Stevenson or Nixon/Kennedy, but an order of magnitude different. From here out, it was too important to defeat Democrats. If that meant Nixon in 1968, then so be it.

The puritanical streak never fully went away, though. The NR crowd, including Burnham, encouraged an abortive right-wing primary challenge to Nixon in 1972.

ALL THE TENSIONS IDEOLOGICAL GROUPS FACE—especially those with pretensions to leadership—are on display here. What is more important, purity or relevance? What about publicity? How do you win the mainstream without compromising too much? How do you deal with the lunatic fringe? We’ve barely mentioned the problem Buckley and NR faced at the same time regarding the John Birch Society.

Despite the temptation of Burnham, the editors at National Review typically chose purity over party—while remaining within touching distance of the GOP as it really was. Voting for, endorsing, or even supporting faulty Republican presidential candidates, they concluded, only strengthened their hold over the party. Of course, NR’s purity meant commitment to hard-right politics unloved by the voters. It’s unclear whether the NR editors’ refusal to engage with Republican moderates was more ideological or social. Aside from the patrician Burnham, they truly hated those ill-formed Republicans. What is generally clear was the disdain of the editors—other than Rusher—for a third party, and especially for the cranks, antisemites, and racists they knew it would attract.

We also see the potent logic of negative polarization at the outset of the conservative movement. You must vote Republican or they will win. It is implicit in the Buckley Rule. In Burnham’s hands, this fear of intellectuals, labor, and the left meant holding one’s nose and joining the moderates. In the bizarro world of the Trump era, it means joining with the cranks, antisemites, and racists as the putative third party has become the GOP. Pace Burnham, perhaps it’s time for conservatives to adopt a holier-than-thou attitude.

Finally, it is true a conservative should see reality as it is. Once, James Burnham argued that meant making peace with the dominant Republican establishment. Yet, to do so today—to make peace with the Trumpist GOP—is to consciously choose a dream over reality: the falseness of the Big Lie claims about the stolen 2020 election, Trump’s regular calumnies, and the very falseness of Trump, a grifter and showman, as an authentic statesman.