How and Why American Communism Failed

Plus: One historian’s about-face on the Communist record.

Reds

The Tragedy of American Communism

by Maurice Isserman

Basic, 374 pp., $35

WRITING IN THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS in 1985, Theodore H. Draper described the “minor academic industry” focusing on American communism as awash in studies written by a younger generation with “political and personal backgrounds in the New Left of the 1960s.” Draper himself represented the field’s old guard: He was a 1930s Red who became an ex-Communist. The problem, as he saw it, was that these younger scholars wore their politics as a “badge of honor,” and they used the history they wrote to “search for a new faith and vision.” Draper concluded that his younger colleagues in the field were guilty of “appallingly sloppy work . . . that is politically motivated.”

In another essay on this topic almost a decade later, Draper went further. He added that the anti-anti-Communist historians were guilty of a “romance” with the American Communist Party of the 1930s that “gives them a safe, warm refuge in the past.” Their project amounted to “an attempt to rehabilitate communism by making it part of the larger family of socialism and democracy.”

One of the most prominent members of the cohort Draper targeted was Maurice Isserman, four decades Draper’s junior. Isserman came from a prominent Communist family that included a CPUSA lawyer, Abe Isserman, Maurice’s uncle. As Draper put it, Maurice Isserman was motivated by the hope, shared with his peers, that “the secret of a new radical rebirth” could be uncovered in the CPUSA’s past through historical scholarship. Draper objected to this “political line and historical bias,” and he singled out Isserman for criticism. The younger historian’s sin, Draper argued, was that he wrote to “do battle with the idea that the Communist party responded ‘blindly to external stimuli’”—meaning, of course, the bidding of the Soviet Union, whose positions their American counterparts always adopted, making whatever adjustments were necessary to conform to whatever the Soviet line was.

Draper was not Isserman’s only critic. Among those who stood in opposition to the New Left cohort was another young scholar of the American Communist Party, Harvey Klehr of Emory University. Isserman and his supporters went after Klehr, who came of age when they did, because he followed the older trends in historical scholarship about the CPUSA: Klehr took an “institutional approach” that stressed “the heavy hand of the Comintern,” as one reviewer of Klehr’s book wrote. Isserman noted that Klehr “used a traditional method of inquiry” and that he was unimpressed by more recent scholarship from those friendlier to American communism. One of Klehr’s points especially rankled Isserman: that the CPUSA’s “special relationship to the Soviet Union” set it apart from other radical movements and ultimately determined its political fate.

So how strange it is to find that today, Isserman’s new history of American Communism, Reds, is blurbed by none other than Harvey Klehr, who writes that Isserman’s is “the best one-volume book on the most important radical organization of twentieth-century America” and praises Isserman for showing how the CPUSA “voluntarily tied itself to a totalitarian regime hostile to democracy.”

What accounts for Isserman’s turnaround?

Our first clue comes at the very beginning of the book’s short prologue. It opens with an epigraph from none other than Draper that includes the line, “It is possible to be right about a part and yet wrong about the whole.” Another quotation nearby comes from Bertolt Brecht, the famed German Communist playwright, who in 1938 wrote, “What is written in the old books is no longer good enough.”

Isserman presumably includes his own older studies among the books no longer good enough, partly right but on the whole wrong.

What does Isserman think he got right? His scholarly cohort used to emphasize the great reforms Communists helped create in Western societies. In Reds, Isserman acknowledges that there is truth in this, but adds that the movement attracted “egalitarian idealists” only to turn them into “authoritarian zealots.” While the CPUSA supported “democratic reforms that benefited millions of ordinary American citizens,” it also “championed a brutal totalitarian state responsible for the imprisonment and deaths of millions of Soviet citizens.”

The most skilled union organizers belonged to the CPUSA, which is why Communists were willingly employed first by the conservative United Mine Workers leader John L. Lewis to organize coal miners into the union he led, and later by the leaders of the growing industrial union movement, the CIO. The CPUSA members took these roles believing the workers they were helping to organize—people who sought job protection and steady and decent wages and benefits—would also come to accept their role ordained by Marx and become shock workers who would usher in socialism. This was an error. As Isserman now puts it, the truth is that “for the most part [these workers] did not support, and often vehemently opposed, the radical restructuring of American society that Communists hoped to achieve.”

Moreover, at times the CPUSA itself acted as a regular American political organization whose members claimed the same protections afforded all groups, such as the constitutional right of free speech. Yet it was “at certain times and places” a “criminal conspiracy” whose leaders approved the activities of a small group of members who worked on behalf of Soviet intelligence agencies, the NKVD—later called the KGB—and the GRU, Soviet military intelligence, and who recruited other party members to do the same. Isserman acknowledges here what he and others long denied. The activities of this subset of the party included “espionage activities” that implicated them in “the theft of the most important military secrets of the [Second World War].” This effort most famously targeted the top-secret Manhattan Project, whose scientists worked to produce the first atomic bomb.

The American Communists’ final failure, Isserman writes, was that although they claimed to be self-critical and rational, they adhered to what they claimed was the “science” of Marxism-Leninism that always was based on “the blindness of faiths.” As a result, despite the good intentions of many party members, the whole project of American communism was based on “bad ideas and bad faith.” Fighting well in advance of other American organizations for such reforms as an end to segregation and full equality for black Americans, its most worthy goals were sacrificed to the complete support of Stalin’s Soviet Union.

TODAY, IT IS WIDELY BELIEVED that a relatively small group, the Democratic Socialists of America, is the largest and most successful socialist group that ever existed in the United States. The truth is that for decades, stemming from the late 1930s through the years of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal to the end of World War II, the Communist Party USA was the largest, most influential and successful socialist group in America. Its members held leading roles in scores of political groups and trade unions, and were influential as well in the arts and sciences.

The early years of American communism began with the heady effect the Bolshevik Revolution had on many American socialists. The belief that a revolution was imminent in the capitalist West led the communists to follow the policy of awaiting a revolutionary crisis that would create a Soviet America. Their tactic was to avoid coalitions with liberals or democratic socialists and to replace existing left groups with revolutionary alternatives, like the National Miners Union, which was the Communist answer to John L. Lewis’s American Federation of Labor (AFL) affiliate the United Mine Workers.

That sectarian policy isolated the party until 1935, when it switched tactics and tried to forma “Popular Front,” an alliance of Communists with mainstream liberals and Democratic activists to pressure the country to move toward the left. FDR’s New Deal led many Communists (or former Communists) to work within existing institutions, including the Democratic party and of course, the union movement.

The split of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) from the AFL empowered the CPUSA. Regular union advocates saw the party members as an existing cadre they could use to do the nitty-gritty organizing work, hence the CPUSA generally was recognized as the force that gained success for the new industrial union movement. In some cases, it wasn’t clear whether the unions were taking advantage of the Communist Party or the other way around. Some large unions, such as the United Electrical Workers and the West Coast longshoremen’s union led by Harry Bridges, fell under Community Party control, as did the National Maritime Union on the East Coast and New York City’s Transit Workers Union, which the party controlled until the early Cold War. The CIO national leadership sought to keep the Communist Party’s role limited to organizing drives, but it also employed party members in influential roles, like Len DeCaux, editor of the CIO News, its national newspaper, and Lee Pressman, its general counsel. (Both DeCaux and Pressman denied their membership for decades.)

While the Communist Party did not control the new United Auto Workers led by Walter Reuther, the party’s success in leading the sitdown strike in Flint, Michigan in 1936 and 1937 put the union on its heels, earning respect and influence for the party members in the union’s ranks. UAW membership, some 90,000 in February of 1937, jumped to 400,000 by the next October. Isserman calls the UAW’s strikes “the most successful worker insurgency in American history,” and party leaders believed they were gaining “newfound legitimacy and relevance” instead of just fighting “perennially lost causes.”

THE CPUSA ALSO BEGAN ITS LONG MARCH through American politics, as its members supported the New Deal and became its left flank, supporting Franklin Roosevelt but trying to push his administration further left. Its strength was immense. It was a large, influential minority in Minnesota’s Farmer-Labor Party, and in a New York City group called the American Labor Party, which ran candidates friendly to the New Deal but critical of it from the left.

Minnesota had a party member in Congress, John Bernard. Party member Hugh DeLacy from Washington was another. A popular New York City congressman from East Harlem, Vito Marcantonio, was likely a secret party member, though he formally represented the American Labor Party from 1937 on (before which he had been a Republican). He served seven terms in the House between 1935 and 1951. There were eventually new black members of Congress elected to the House, a few of whom were suspected to be CPUSA members, and were openly supportive of many of the party’s chosen causes.

Certain CPUSA state affiliates were also influential. The California Communist Party became, in essence, a strong faction within the California Democratic Party, supporting another leader friendly to if not a member of the party, Culbert Olson, who won the governorship in 1938.

During World War II, CPUSA Chairman Earl Browder dissolved the party and made it a political association that sought to work within the liberal mainstream and through the ranks of the Democratic party. Browder announced that a socialist revolution would not take place in the Western nations and that class struggle would dissipate. The party had to become part of what he called the “American political tradition.” During the war, the CPUSA became the Communist Political Association, no longer functioning as a Leninist group but as a regular pressure group that was part of a broad liberal coalition. By the end of the war, Isserman writes, the CPUSA had become “a movement of native-born radicals, with deep roots in the labor movement, who felt at home in America.”

Browder’s new policy was short-lived. As Stalin started to wage the Cold War, he demanded that Browder be removed from his leadership role in the party, that class struggle be resumed, and that the Leninist party structure be reimposed on to the American Communist movement.

From 1945 to 1947, despite Browder’s expulsion and the resumption of a Leninist party structure, for a time “Communists continued to play influential roles in mainstream politics in at least a half dozen states.” The re-Stalinization of the CPUSA was one half of the scissors that severed the wartime Communist-liberal Popular Front. The other half was the liberal opposition to Stalin’s foreign policy.

In 1948, after the Czechoslovak Coup and during the Berlin Airlift, the CPUSA endorsed Progressive Party nominee Henry A. Wallace for president on a platform demanding support of Stalin’s foreign policy as the only way to peace. Organizations the CPUSA controlled or influenced were ordered to endorse Wallace and oppose Harry S. Truman, whom it accused of paving the way to a fascist state in America and to waging an imperialist war. The alliance with liberals was dissolved.

ISSERMAN DEPARTS FROM HIS OLD ANALYSIS of American communism in one major respect: He has come to accept the evidence that the American Communist Party worked with Soviet intelligence to recruit members to work for and with the major Soviet spy agencies, especially the KGB and GRU. When party members were drafted to spy—referred to in their vernacular as doing “secret work”—they were instructed to quit their political activity and membership with the party and devote themselves to the requirements of espionage.

“Fear of Communist subversion was overblown, of Communist sabotage spurious. The same cannot be said of Communist espionage. There were spies,” Isserman writes. Elizabeth Bentley opened an early window on these activities. She had run a spy ring in the federal government during the war but left the fold and approached the FBI to confess her treason. While testifying to a federal grand jury, she described the network of espionage groups she directed, earning her the moniker “The Red Spy Queen” in headlines about the affair. Isserman describes her as “erratic,” but accepts that “much of what she had to say was corroborated by other FBI sources.” This typifies Isserman’s larger evolution: He has come to accept that the most prominent of those accused and brought to trial—people like former State Department official Alger Hiss, and atomic spies Julius Rosenberg and David Greenglass—were all guilty. “While wearing the uniform of his country,” Isserman writes, Greenglass “passed military secrets in wartime to a foreign power.”

All these American Communist spies helped Soviet intelligence to achieve “spectacular success” before high-profile defections brought down its networks. But the majority of American CP members were unaware of their comrades’ “secret work” and hence “sincerely regarded” the spying allegations as mere “witch-hunting.” Isserman now acknowledges they were wrong: CPUSA leaders had betrayed their followers and their own cause, he writes, “implicating all Communists by association in crimes in which they had no knowledge or involvement.” The result was that American Communists “would never shed the stigma in popular memory of the fatal involvement of a few with Soviet intelligence in the 1930s and 1940s.”

THERE IS ONE AREA IN WHICH I DISAGREE with Isserman. Cold War liberals formed organizations like Americans for Democratic Action that did not welcome Communists as part of a larger policy of denying membership to both far-left and far-right totalitarians. Yet Isserman argues that they “embraced a hope as woolly-headed and utopian as any held by the most naive of Henry Wallace’s fellow-traveling supporters.” This argument, I think, is wrong.

Unlike Wallace’s supporters, other fellow travelers, and holdover Communists, these new anti-Communist liberals supported both the Marshall Plan to reconstruct Europe and the creation of NATO. The latter worked to protect their nations against any attempts of Stalin to expand the Soviet-style puppet regimes known as “people’s democracies” to the West and take power in nations like France, Italy, Hungary, and Poland. So why shouldn’t these new Cold War liberals show that they were just as concerned as the Republicans “with countering the threat of foreign and domestic Communism as their hyper-partisan Republican opponents”? Their defense of their anti-Communist bona fides was grounded in the truth; their support of bipartisan foreign policy stopped a threat to it from both left-wing isolationists and the obstructive right that worked hard to oppose Western unity, including its military component. Far from being “woolly-headed,” Cold War liberalism was a picture of pragmatic midcentury politics.

This becomes particularly clear when we draw the contrast with the leaders of the CPUSA. As Isserman acknowledges, the party took Stalin’s new tough foreign policy to mean that they could “expect a general revolutionary upsurge in coming years.” In light of this messianic hope, they took new positions—including mounting a third-party bid in the election of 1948—that siloed them politically and brought to an end the role they had played in the American union movement, which supported Truman’s foreign policy. The result is that the American Communists threw their “hard-won gains away,” including the fruits of the three decades the CPUSA had spent helping to build the CIO, which had earned them a measure of real political power. Waiting for the new world, the CPUSA lost whatever grip it had on the current one, which the Cold War liberals instead would help to shape.

WHAT MAURICE ISSERMAN HAS ACCOMPLISHED in this well-written and superb history of the American Communist Party is a fresh assessment that will force many who have previously studied the party to revise some views. Fellow-traveler historians rejected any critical views of the party’s role, and argued that Communists valiantly fought to expand American freedom and dismissed the accusations of espionage against party members as unwarranted McCarthyite attacks. Even the historian Eric Foner argued that “the tiny Communist Party hardly posed a threat to American security” and that its members were guilty of “nothing more than holding unpopular beliefs and engaging in totally legitimate political activities.” Isserman has put an end to the argument of those who still believe in the Communist Party’s total innocence.

In contrast, the anti-Communist liberal Sidney Hook famously wrote first in a 1950 article in the New York Times titled “Heresy, Yes—But Conspiracy, No,” later expanded into a book by the same title, that the CPUSA was a conspiracy on behalf of the Soviet Union under Stalin and hence its members could not be judged by the standards used to discuss arguments made by advocates of other doctrines. The Communist teacher, for example, was not expressing a heretical idea; he was under Communist Party discipline and was in fact advocating for revolution and subservience to policies of the Soviet Union, thus was not engaging in ideas that could be freely debated. Even those who had no connection with espionage, in Hook’s eyes, were part of the conspiracy.

Isserman establishes that in fact, many American Communists struggled to wage a good fight for things like full civil rights for black Americans at a moment when others either gave it mere lip service or supported Jim Crow laws. Yet these same Communists who often made sacrifices to expand American democracy would, when instructed, betray their own country and become spies for the Soviet Union.

In fact, the party frequently put aside its principles—egalitarian, revolutionary, or otherwise—for the sake of political expediency. During World War II, the party was so loyal to the Roosevelt administration that it gave its tacit support to the internment of Japanese Americans, even though American Communists of Japanese descent were among those rounded up and imprisoned there. Similarly, the CPUSA approved of the Justice Department’s successful prosecution of a group of Trotskyist leaders of the Teamsters Union in Minnesota under the Smith Act, which criminalized advocating the overthrow of the U.S. government by force and violence, and later cheered any government crackdown against anti-war groups. The Trotskyists, unlike the CPUSA, viewed the American war effort as an imperialist act of aggression. Ironically, during the postwar Red Scare, major CPUSA leaders were convicted under the same law.

As Isserman notes at the book’s end, the CPUSA still exists, but as a shell of its former self, and without a Soviet state to support and secretly finance its existence. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the abandonment of the American party by many of its longstanding members made its decline inevitable. The party no longer makes its membership numbers available, and its programs and activities are indistinguishable from other socialist groups, especially Democratic Socialists of America, whose members often cooperate and attend demonstrations with them.

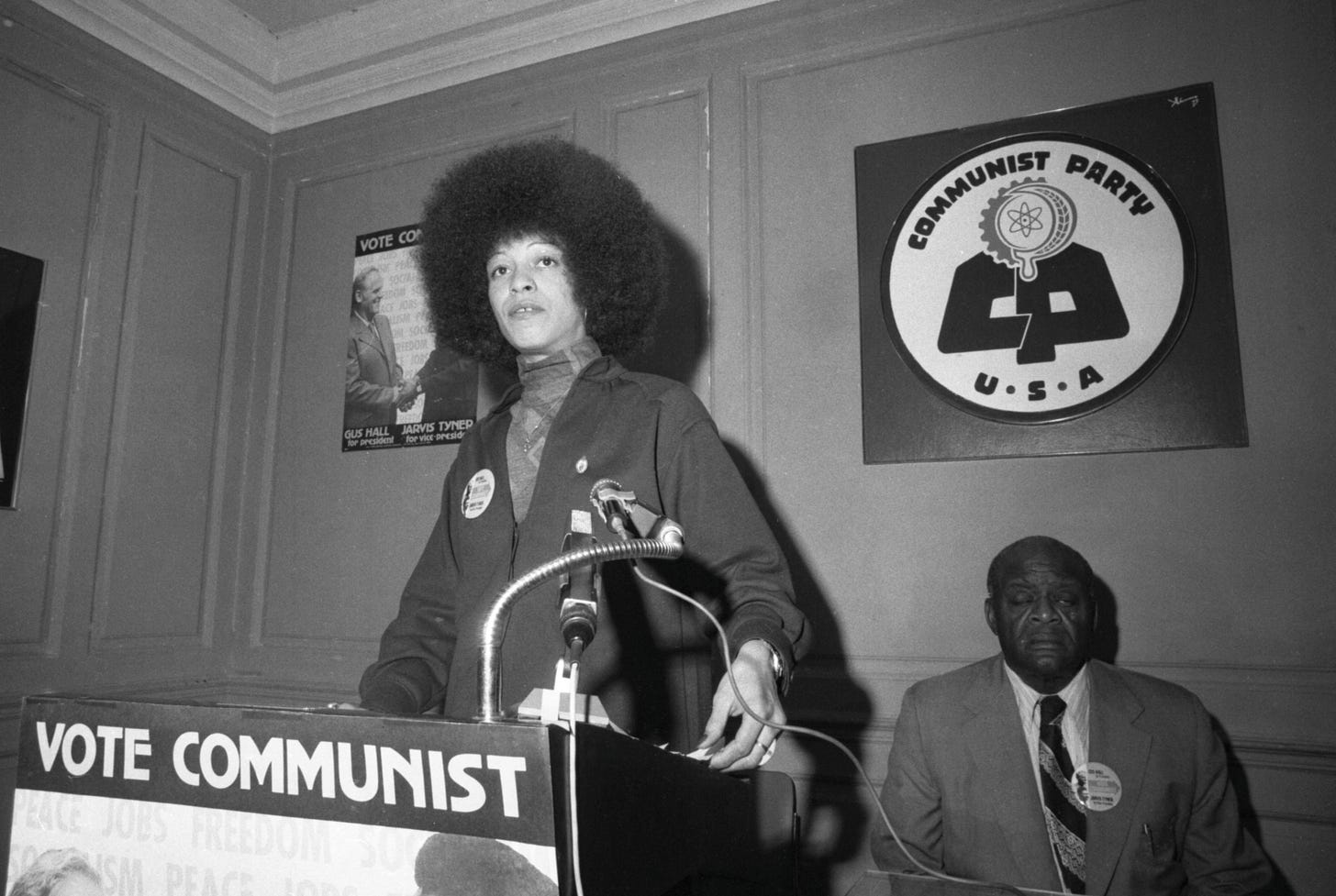

After the fall of the Soviet Union, even its most ardent hardliners like the Communist historian Herbert Aptheker and the party’s biggest star, longtime activist Angela Davis, began to hold doubts about its viability. Aptheker, a supporter of the Soviet invasions of Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968, admitted in 1991 that the Soviet leaders had been guilty of “monstrous crimes” including “mass murder” and “massive human extermination.” As for his own party, its members “were easily deceived” as well as “credulous because we felt we had to be.”

The CPUSA ended, as Isserman writes, as a party composed of “nothing but ashes.” The building it owns and uses for its headquarters in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City, however, is valued at $9 million, allowing its few members to continue to pretend they belong to an influential mass political organization.

There is a role to play in the United States for a serious political left to challenge the assumptions of the center-left and center-right and raise issues the mainstream parties and movements would otherwise ignore. But, as Maurice Isserman’s book reveals, the Communist Party USA could never have served that purpose—because a healthy left, unlike the CPUSA, would be a loyal opposition, acting in the best spirit of the American experiment rather than supporting its enemies.