The Creative Joy of a Cold, Dead Winter

Val McDermid’s new book evokes an earlier Scot’s love of the bleak.

SCOTTISH CRIME NOVELIST VAL McDERMID has written more than thirty novels that together have sold more than nineteen million copies. Yet she clearly takes special pride from the speech she gave in a Masonic hall in the village of Bowhill, Scotland, on January 28, 2023. Members of the Bowhill People’s Burns Club, founded during World War II, convened for the Eighty-Third Annual Burns Supper—an evening of ceremony, toasts, songs, and recitations dedicated to the nation’s favorite bard, Robert Burns. McDermid was the first woman ever to deliver the night’s central toast.

“No other poet,” she said, “inspires such affection nor so diverse a fan club” as Burns, for “his verse is rooted in the experiences of ordinary men and women.” Burns wrote of our shared lives: “desire and its consequences,” “loss and failure,” and “the unfairness of the world.” McDermid lauded Burns for his passion (for verse, and for women), for his ability to collect traditional Scottish songs and refine them “into the gems we know now,” and for his incredible range. Burns wrote “passionate love poems, social satire, comedy, politics, haggis, attacks on hypocrisy, bawdy songs about sexual adventures, not to mention subversive sideways swipes at political and ecclesiastical elites.”

Perhaps most personally for McDermid, though, Burns reflected her father, “a working class man who left school at fourteen,” and “saw his own world view in the words” of the poet. Jim McDermid “was the lead tenor in the club’s concert party—no mean feat when between them, the club’s hundred members can perform over sixty poems or songs from the bard’s repertoire.” (Her father was also a scout for the Raith Rovers football club, and was the first to discover legendary footballer Jim Baxter.)

Tradition is important to McDermid, and inextricable from a sense of season. Her new nonfiction book, Winter: The Story of a Season, captures life as a series of refrains, and in such cycles we carry ourselves into eternity.

ROBERT BURNS WAS BORN in the middle of winter—January 25, 1759. In the early spring of 1784, he wrote in a letter of “the peculiar pleasure I take in the season of winter, more than the rest of the year.” The season gave his mind “a melancholy cast.” He loved “to walk in the sheltered side of a wood, or high plantation, in a cloudy winter-day, and hear the stormy wind howling among the trees, and raving over the plain.”

The son and grandson of farmers, Burns, like W.B. Yeats after him, was drawn to the stories of his national tradition. He was perhaps most formed by a local woman named Jenny Wilson, who had “the largest collection in the country of tales and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, browies, witches, warlocks, spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips, giants, enchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery.” Her fantastical stories “cultivated” in young Burns “the latent seeds of poesie.” He called Wilson’s collection of Scottish songs his “vade mecum” (“go with me” in Latin—a handbook), and he “pored over them, driving my cart or walking to labour, song by song, verse by verse, carefully noting the true, tender, or sublime from affectation and fustian.”

Burns brought together those rhythms and the season of his birth in one of his earliest poems, “Winter, a dirge.” He wrote the poem “in such a season, just after a train of misfortunes.” He embraced the paradoxes of those months:

The sweeping blast, the sky o’ercast, The joyless winter-day Let others fear, to me more dear Than all the pride of May: The tempest’s howl, it soothes my soul, My griefs it seems to join; The leafless trees my fancy please, Their fate resembles mine!

Little wonder the eminence of Tartan noir is a fan.

IF BURNS IS THE POET LAUREATE OF SCOTLAND, then McDermid is the laureate of the lascivious. She writes of killers and sexual deviance. Her novels are smart, sinister, and often comic. Like Burns, she is drawn to winter’s mysterious whispers.

Winter is her season of creativity. She travels on trains, not planes, and likes to jot “gnomic lines” in various notebooks. For her, trains are a place of imagination, but also a reminder that the rest of the world keeps moving while she is engrossed in her art.

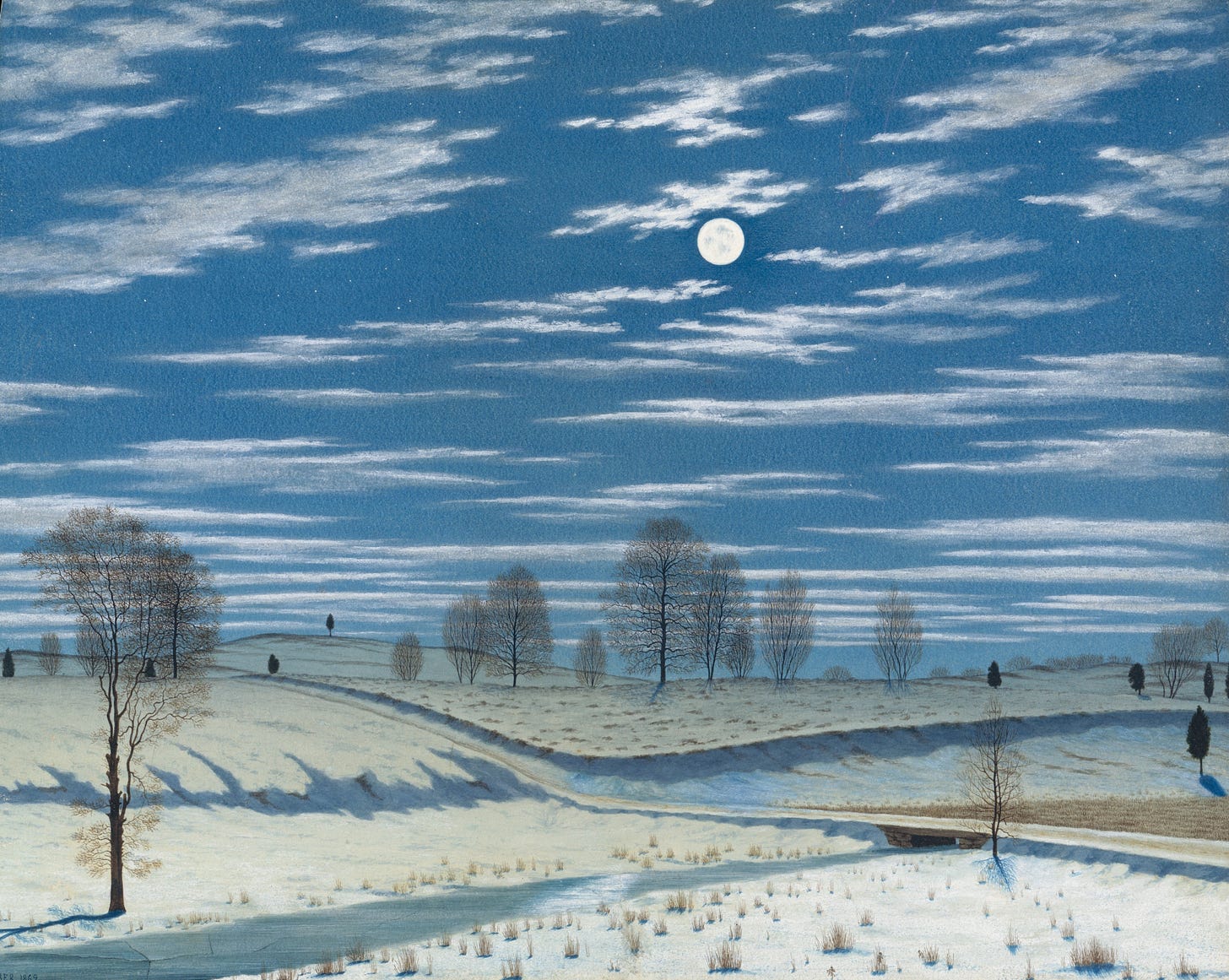

McDermid starts writing new books in January. “The weather is invariably inhospitable so there are few temptations to pull me away from the business of crafting those early pages.” As it did for Burns, winter stirs her soul. At her writing desk, she looks outside to see how “the branches and twigs form a kind of road map. Tracing their paths is the perfect mindless activity when I need to let the wheels turn so the next piece of prose can form in my head. Winter makes it easy to follow strange tracks in my mind; summer is less straightforward, obscured by green.”

Winter trees were a poetic lodestar for Burns. In a 1785 poem written to his friend William Simpson, a schoolmaster in the village of Ochiltree, Burns described:

Ev’n winter bleak has charms to me, When winds rave thro’ the naked tree; Or frosts on hills of Ochiltree Are hoary gray; Or blinding drifts wild-furious flee, Dark’ning the day!

Although Burns could be bawdy and boisterous, he tended to be more solemn, even reverential, when writing about winter. It was a power that transcended his puns and parody. I suspect that is why McDermid is so drawn to her poetic predecessor: There was a time, a place, and a verse appropriate to the moment.

“I love winter precisely because it’s Janus-faced,” McDermid writes. “It’s nature’s equivalent of what the poet Hugh MacDiarmid called the Caledonian antisyzygy—the yoking together of opposing forces. He characterized Scottish nature as composed equally of stern, forbidding Presbyterianism and the dancing, musical, wildness of the Gaels.” McDermid is preternaturally Scottish. Although she is a novelist, she is a troubadour. Winter teems with gorgeous sentences.

She writes of driving to Dundee University to deliver a lecture one December. “The road gleamed black in the moonlight, a dark ribbon threading through the trees and the undergrowth on either side of the road.” Covered with frost, “the grasses, the bracken and the branches shone brilliant white like ghosts of themselves.” That particular winter followed “a mild and wet autumn,” causing “more woodland marcescense than usual, and those dead leaves hung stark white on the branches like albino bats, unmoving in the still air. It felt like driving through a dreamscape, a night in Narnia absent only the talking animals. That there were almost no other cars on the road added to the otherworldly feeling.”

McDermid believes that in winter, “we need something to take our minds off the privations of the season.” The season wears us down. “We’re muffled up in wooly jumpers and big boots, raincoats are never enough to keep us warm for long, and we lose the light so quickly that even simple pleasures like a woodland walk are constrained by the early dark.” Cold and forlorn, “we embrace whatever excess we can find.” Sometimes a book can give us such pleasure.Winter suggests that rather than read our way out of our surroundings, we instead look anew at the quotidian. We are steeped in old, strange stories, and often they merely need some new syntax.