The Department of Defense’s ‘Strategy’ Is More Like a Wish List

The military needs more than campaign slogans and political rhetoric.

IN LATE 2001, AFTER THE SEPTEMBER 11TH ATTACKS, President Bush’s National Security Council did what strategy demands in moments of danger: It reassessed the world as it was, not as we wished it to be, and published a new National Security Strategy. That document acknowledged a transformed threat environment and subsequently articulated national objectives that reflected what the government would need to do. Immediately afterward, as is always the case, the Joint Staff—i.e., the organization that reports to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and handles issues like personnel, intelligence, logistics, and planning for the military as a whole—was tasked with producing a National Defense Strategy (NDS) that translated those new national goals into updated military guidance.

As a contributor to that Joint Staff effort, I have been revisiting that experience since the Department of Defense issued its 2026 NDS last week. I helped write a defense strategy during a genuinely dangerous period, when the consequences of error were immediate and unforgiving. I saw what a serious NDS provides to the force—not inspiration or affirmation, but clarity. National strategy documents matter because real actions flow from them: budgets, force design, training and operational priorities, engagement with key allies, readiness models, and leader requirements, to name a few.

Ideally, any White House National Security Strategy defines the foreign policy goals for the whole government, and then sets about reasonable (if not specific) plans to achieve those goals. The follow-on National Defense Strategy then tells the Department of Defense how the military will work to help implement those plans and achieve those goals. When done well, this process disciplines choices. When done poorly, it creates confusion that echoes for years across the military force.

That is why the 2026 NDS is so concerning. Not because it sets changed or ambitious goals, but because it repeatedly substitutes political rhetoric and untested assumptions for the strategic guidance the military requires.

From its first pages, the 2026 NDS devotes considerable and valuable space to openly and directly criticizing previous administrations. The very first sentence of Secretary Pete Hegseth’s cover memo, which sets the tone not only for the whole publication but for his department’s strategy in toto, is retrospective and retributive, rather than prospective and mission-oriented: “For too long, the U.S. Government neglected—even rejected—putting Americans and their concrete interests first. Previous administrations squandered our military advantages and the lives, goodwill, and resources of our people. . .” The National Defense Strategy proper continues in that vein on the very first page of text: “Rather than husband and cultivate . . . hard-earned advantages, our nation’s post–Cold War leadership and foreign policy establishment squandered them.”

The tone is unmistakable—and misplaced. Strategy documents are not campaign speeches, and they should not be party propaganda. They are not vehicles for settling political scores; they are meant to speak to a professional force tasked with executing national objectives under extreme risk.

To put it another way: To an admiral responsible for responding to encroachment and aggression by the Chinese Navy, Hegseth’s opinion of the foreign policy of the Clinton administration—when that admiral was probably a lieutenant in the middle of the ocean somewhere—isn’t really important. What this administration wants him to do about China, and what resources it’s going to give him—that’s what’s important.

THE KIND OF ANALYTICAL RIGOR and clarity a National Defense Strategy needs to be successful are painfully lacking from this document. Many of the examples used to disparage former leaders and past policies are oversimplified if not demonstrably inaccurate, and they offer little insight to military planners or commanders. This typical paragraph condenses entire wars down to simple phrases and flattens the complexity of war, strategy, and competition into bite-size vignettes:

The fact is that President Trump took office in January 2025 to one of the most dangerous security environments in our nation’s history. At home, America’s borders were overrun, narco-terrorists and other enemies grew more powerful throughout the Western Hemisphere, and U.S. access to key terrain like the Panama Canal and Greenland was increasingly in doubt. Meanwhile in Europe, where President Trump had previously led North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies to begin taking their defenses seriously, the last administration effectively encouraged them to free-ride, leaving the Alliance unable to deter or respond effectively to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In the Middle East, Israel showed that it was able and willing to defend itself after the barbaric attacks of October 7th—in short, that it is a model ally. Yet rather than empower Israel, the last administration tied its hands. All the while, China and its military grew more powerful in the Indo-Pacific region, the world’s largest and most dynamic market area, with significant implications for Americans’ own security, freedom, and prosperity.

That rhetorical emphasis is flawed, and that matters because when political messaging displaces analytical rigor, strategy becomes affirmation rather than direction.

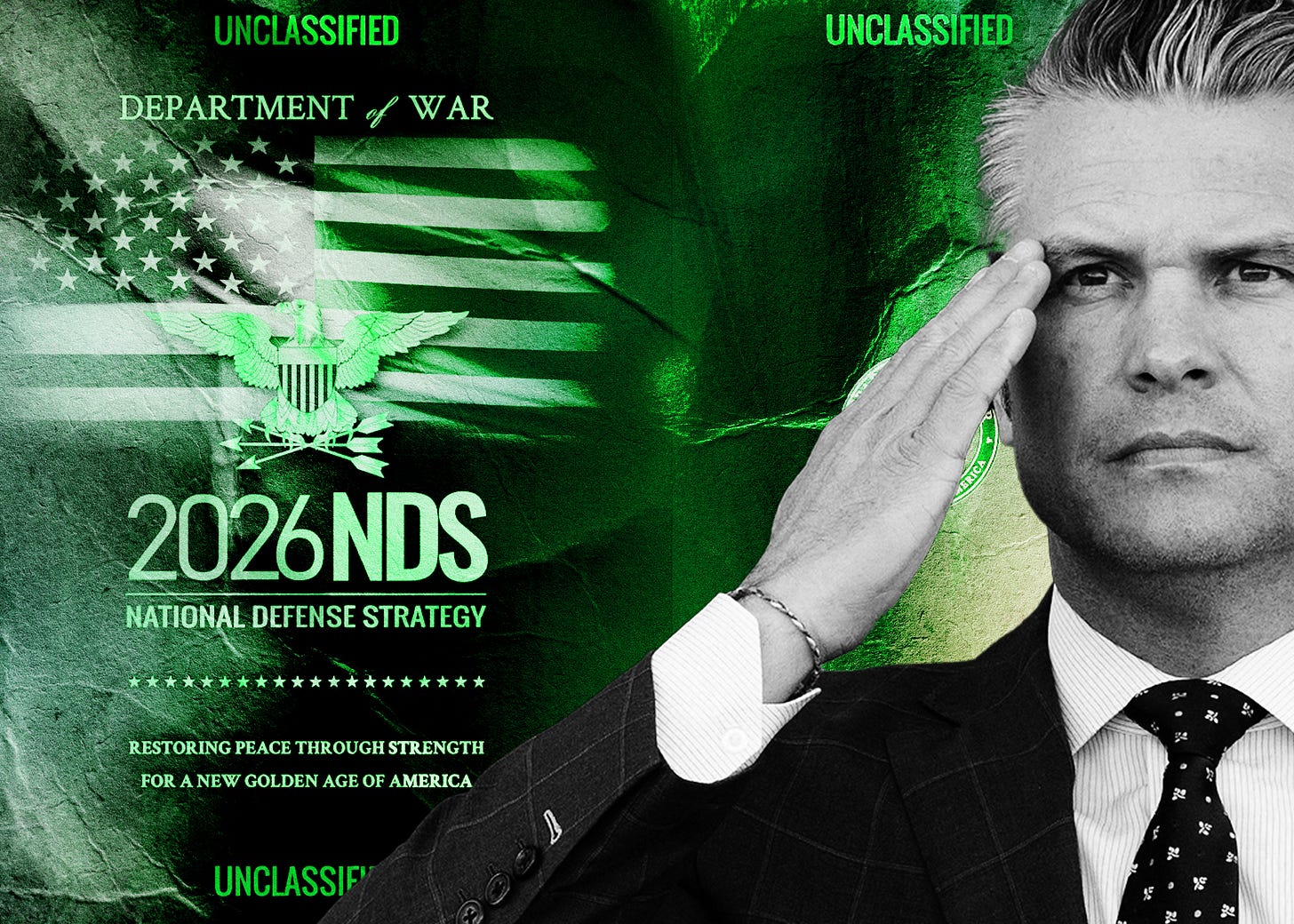

That emphasis is also reinforced visually. The unclassified version of the 2026 NDS is dominated by multiple photographs of President Donald Trump and Hegseth, while only a single image—on page 15 of 25—depicts uniformed military personnel alone. That may seem petty, but to the force, symbols matter. A defense strategy exists to guide the profession of arms, not to celebrate civilian personalities. When strategy documents drift toward sycophancy, and this one does repeatedly, they lose credibility with the very institution they are meant to lead.

Most importantly, the document treats assumptions as conclusions. Declarative language—will, must, expect—is used as if asserting a described outcome is guaranteed. This was one reminder of the most enduring lessons from my time in the Pentagon: the danger of unexamined assumptions. No one reinforced that lesson more relentlessly than Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

Rumsfeld was particularly demanding when combatant commanders briefed their theater contingency and war plans. I was in those rooms, watching and taking notes, because I served in the Joint Staff section responsible for reviewing war plans. I watched closely as four-star generals and admirals walked through their concepts with their civilian leader. They were continuously peppered with questions—not because Rumsfeld wanted them to know he was smart, but because probing challenges tested their understanding of cause and effect, second- and third-order consequences, and their intellectual capacity to adapt when their assumptions proved dangerous or wrong.

Those exchanges were uncomfortable for everyone in the room by design. They forced commanders to confront the fragility of plans built on best-case scenarios. They revealed whether a concept was resilient or brittle. And they taught me what to look for in strategy documents.

This NDS outlines four “lines of effort,” and with Rumsfeld and other demanding past bosses in my ear, I found that each of them warrants close scrutiny.

1. Homeland Defense Without Prioritization

The strategy places homeland defense at the top of its agenda, emphasizing border security, counter-narco-terrorism, and domestic resilience. Protecting the homeland is unquestionably a core mission. What is missing is prioritization and integration.

The document does not clearly articulate how these missions compete with or complement other defense requirements, nor how resources will be shifted without degrading readiness elsewhere. To take one example:

Modernize and Adapt U.S. Nuclear Forces. The United States requires a strong, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal adapted to the nation’s overall and defense strategies. We will modernize and adapt our nuclear forces accordingly with focused attention on deterrence and escalation management amidst the changing global nuclear landscape. The United States should never—will never—be left vulnerable to nuclear blackmail.

Is the Defense Department intending to imply in this short paragraph that U.S. policy is now that nuclear weapons are solely for the defense of the homeland, and that America’s “nuclear umbrella” is now closed? If so, some American allies should be rightly concerned. And if U.S. allies can no longer depend on America’s extended deterrence, how does that effect the burden-sharing among allies addressed in Line of Effort 3 (discussed below)? The document doesn’t say.

Homeland defense is presented as an imperative, not a problem to be managed with finite means or in relation to other goals. Strategy requires trade-offs; this first section largely avoids them.

2. Indo-Pacific Deterrence by Assertion

Deterring China is treated as a central organizing principle of the strategy. Again, the objective is sound. The guidance on execution is not.

The NDS asserts deterrence rather than explaining how it will be sustained under conditions of stretched forces, contested access, and political constraints among regional partners. It assumes alignment without grappling with the limits of partner capacity or political will. It assumes allies will play the role we dictate, and that regional deterrence is achieved through declarations. Experience and history show that countering a determined competitor like China is maintained through a credible posture, persistent presence, and sustained engagement with solid allies—none of which can be improvised or simply spoken into being.

3. Alliances as Instruments, Not Relationships

The most consequential flaw in the 2026 NDS lies in its treatment of alliances. The document assumes allies will do exactly what the United States asks of them—quickly, fully, and without question or friction.

Recent events suggest otherwise. Just this week, after President Trump’s insistence on the takeover of Greenland, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni voiced the potential of resistance to presumptive U.S. use of critical air and naval bases in Italy. This is just the most recent reminder that allies are sovereign actors, not extensions of American will.

The administration got another reminder last week, when it announced the members of Trump’s “Board of Peace”: Two of the last communist regimes in the world, Cambodia and Vietnam, have signed on, as have Belarus and Pakistan—not exactly America’s most capable allies. Norway, Sweden, the UK, Germany, France, and Spain—all American treaty allies, who are also some of this country’s oldest and closest friends—all declined.

For decades, U.S. commanders in Europe and the Pacific lived by a simple truth: Trust cannot be deployed at the last minute. It is built by presence, predictability, and respect—by being there, training and exercising in multinational formations, operating together before a crisis. The 2026 NDS appears to presume the opposite: that trust can be generated on demand, even as alliances are publicly disparaged or taken for granted.

That is not how alliances work, and the uniformed personnel in the Department of Defense knows that, even if their civilian leaders do not.

4. Industrial Base Ambitions Without Realism

Finally, the strategy places heavy emphasis on revitalizing the defense industrial base, both to meet U.S. needs and to supply allies. The goal is important. The assumptions are optimistic.

Building industrial capacity requires time, skilled labor, stable demand, regulatory reform, confidence among foreign buyers that the United States will remain a reliable partner, and something the president himself cannot guarantee: bigger appropriations from Congress for acquisition. The stated strategy largely ignores these constraints, assuming capacity and demand will materialize because they are declared necessary. Industrial capacity, like alliances, cannot be commanded into existence.

THE NATIONAL DEFENSE STRATEGY I worked on a quarter-century ago was far from perfect. But it did something essential: It provided guidance that forced choices, exposed risks, and disciplined the institution charged with execution. It spoke to the military as a profession, not as an audience tied to a political party.

The same can’t be said of the 2026 NDS. It confuses swagger with credibility, assertion with analysis, and cocky proclamations with leadership. Strategy should make leaders uncomfortable in productive ways. It should question assumptions, not enshrine them.

In dangerous times, clarity is a form of protection. The 2026 National Defense Strategy offers far too little of it.