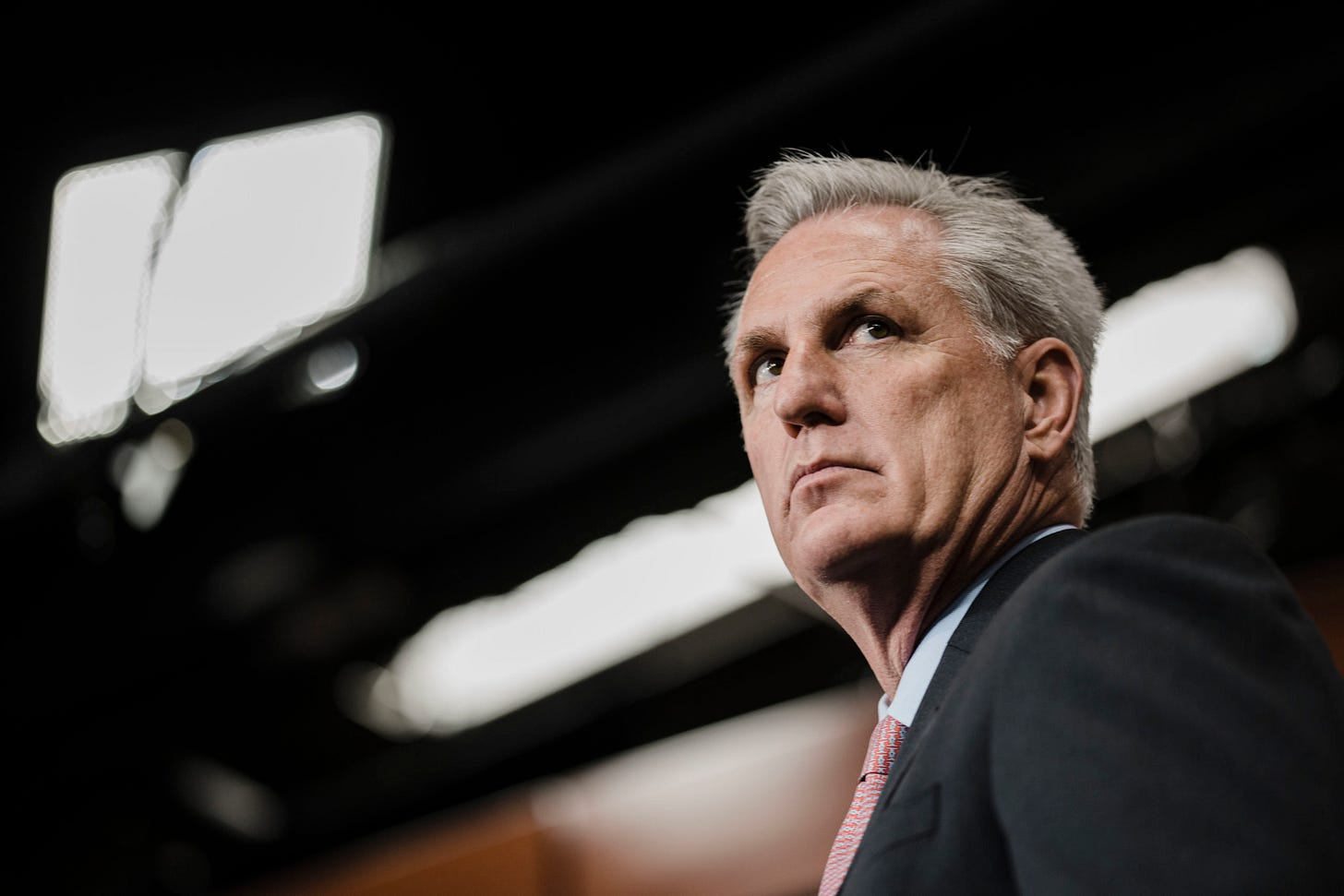

Did Kevin McCarthy Really Have a Moment of Conscience?

Or was even his anti-Trump posture a calculated act of ambition?

When Kevin McCarthy got blown up by the New York Times last week, the conventional explanation for his lying (and then lying about his lying) was that it was all because, in the heat of the insurrection, he’d had a pang of conscience—and then later regretted it.

And maybe that’s true. But what if the explanation is even simpler? What if there was never any internal debate between conscience and ambition, let alone one in which conscience briefly (and incompletely) won out?

Prior to Jan. 6th, Kevin McCarthy lavished praise on Trump because he thought that was the clear path for him to become speaker of the House, a post he has very publicly coveted. This we can take as given.

Likewise, ambition was the obvious motivation for McCarthy to return to Trump toady status in the days following the insurrection.

But during that brief interregnum—in which McCarthy and Cheney discussed the Twenty-fifth Amendment and his own recommendation that Trump resign—perhaps McCarthy imagined there would be an outcry even within his own party over Jan. 6th. Perhaps he thought that eventually getting the speaker’s gavel depended on ushering Trump offstage.

Maybe it was just ambition all the way down.

Now, of course, this isn’t either/or. Human decision-making is not monocausal. But insofar as one attributes motive, the ratios matter. Was McCarthy mostly doing (or at least saying) the right thing because he was horrified by what he’d just witnessed and felt a rare obligation to perform his constitutional duties in response? Or was he mostly doing the right thing for the wrong reason, his desperate desire to become speaker—which is the precise same motive that impelled him to ritually abase himself before Trump both before and after?

It was a reasonable calculation (though ultimately an incorrect one) for McCarthy to think his ambitions required a break with Trump after the latter inspired a violent assault on the U.S. Capitol. Even Mitch McConnell, who plays the game as well as anyone, clearly entertained the possibility, practically crying out to Democrats, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent president?” and explicitly raising the possibility of post-presidential prosecution.

And no one has ever accused McConnell of allowing moral concerns to dictate his actions.

So just as an Occam’s Razor exercise, “McCarthy’s motives never changed at all” is a more straightforward explanation than “McCarthy’s motives briefly became more decent and recognizably human, but then changed back.”

So why is it that so many of us—including myself, incidentally—intuitively presumed that McCarthy’s motives for (apparently) contemplating a genuine break with Trump were inspired by genuine moral shock and/or a concern for the good of the nation?

Well, it is a fundamental human trait that we believe that the actions we like are undertaken for good motives, and the ones we dislike are undertaken for bad ones. Call it a version of motivated reasoning, or correspondence bias, or the halo effect, or whichever psychological term you prefer. It is clearly a thing.

When people who revile Trump see McCarthy doing the obviously right thing, we presume it’s for the right reasons. Because we’re projecting our own moral judgments onto him.

So really, what you think of McCarthy’s moment of clarity probably says more about your own values than it does about his.

This is true in ways that can be both flattering and unflattering. Take Chris Christie, who went on ABC’s This Week and described McCarthy’s stance in the phone call as “If the Senate is going to convict [Trump], then I would advise him to resign”—i.e., to spare him the ignominy. In Christie’s telling, McCarthy was still on Trump’s team, looking out for Trump’s best interests, the whole time! McCarthy merely recommended the best of the suboptimal options available to Trump. You know, the way you’d counsel any friend. Christie added that he thought this had been “pretty smart advice.”

And here’s the thing: Christie’s reading sounded like spin. But it is in fact completely plausible—probably more plausible, based on the tape, than the “pang of conscience” explanation. If you haven’t listened (or even if you have), give it another listen. In the clip, McCarthy doesn’t sound angry, or disgusted, or any of the other emotions one might normally associate with a violent attack on the U.S. Capitol. And he chooses his words slowly and carefully, like a man who is weighing, in real time, what is the least politically dangerous thing for him to say.

And what precisely does he say? “I’m seriously thinking of having that discussion” with Trump. “What I think I’m going to do is, I’m going to call him.” He doesn’t commit to making the call—and there’s no sign that he ever did—and he certainly offers no suggestion that he had any intention of putting pressure on Trump. McCarthy basically says, This is the advice I’ll probably give him, but I doubt he’ll listen.

In a leadership call the next day, also leaked, McCarthy claimed that he’d had a phone chat with Trump, in which (a) McCarthy forcefully pressed him to accept some responsibility for Jan. 6th, “no ifs ands or buts”; and (b) Trump did accept some responsibility. I’ll leave it to the individual reader to decide which of these two claims is the more improbable. But given that both men insist the call never happened, I think the most reasonable assumption is that McCarthy was mostly or entirely lying.

And let us not forget: When he discussed Trump’s possible resignation, McCarthy was answering a question from Liz Cheney. You can almost hear him trying to balance what Cheney clearly wanted him to say—some variation on Get the bastard out of here—and what might get him in trouble elsewhere. McCarthy’s longtime reputation is as a people pleaser, which, depending on circumstances, can be a good or a bad thing. It is, however, a very bad thing when the principal person you want to please is a depraved, soon-to-be-ex-president who incited violence in an effort to steal the election.

Don’t believe me? Let’s check in with the man himself. Washington, D.C. spent the better part of a week ablaze with the idea that Trump would be furious with McCarthy and would personally nuke his chance of ever becoming speaker. But the opposite happened. On Friday, Trump told the Wall Street Journal that he “didn’t like” the leaked call, before adding, “But almost immediately as you know, because he came here and we took a picture right there”—the infamous Mar-a-Lago photo taken when McCarthy visited, later in January—“you know, the support was very strong.” Trump went on, “I think it’s all a big compliment, frankly. . . . They realized they were wrong and supported me.”

Why did Trump respond this way? It certainly wasn’t because he thought the leaked calls revealed that McCarthy had some previously hidden moral core or genuine political principles. It’s because it revealed that he didn’t.

McCarthy talked tough (semi-tough? quarter-tough?) to members of his conference, and then almost immediately resumed kowtowing to Trump. The ex-president likes his many perpetual grovelers and bootlicks fine. (See, again: Chris Christie, whose serial humiliations included the fabricated “we sent him to get hamburgers” story.) But what he really likes is someone who visibly fears him. Someone who may occasionally offer feeble resistance, but whom he knows that he can break at will, any time he wants.

The primary lesson of the McCarthy tapes, and Trump’s reaction to them, is that Kevin McCarthy is precisely that kind of man.