‘Dream Scenario’ Review

Meme scenario.

DREAM SCENARIO IS NOMINALLY about a handful of trendy topics—notions of the day like virality and cancel culture and out-of-control college kids demanding everyone acknowledge their lived experience and bow to their claims of trauma—but it’s really about an age-old idea: the crushing inability to be happy with what we have.

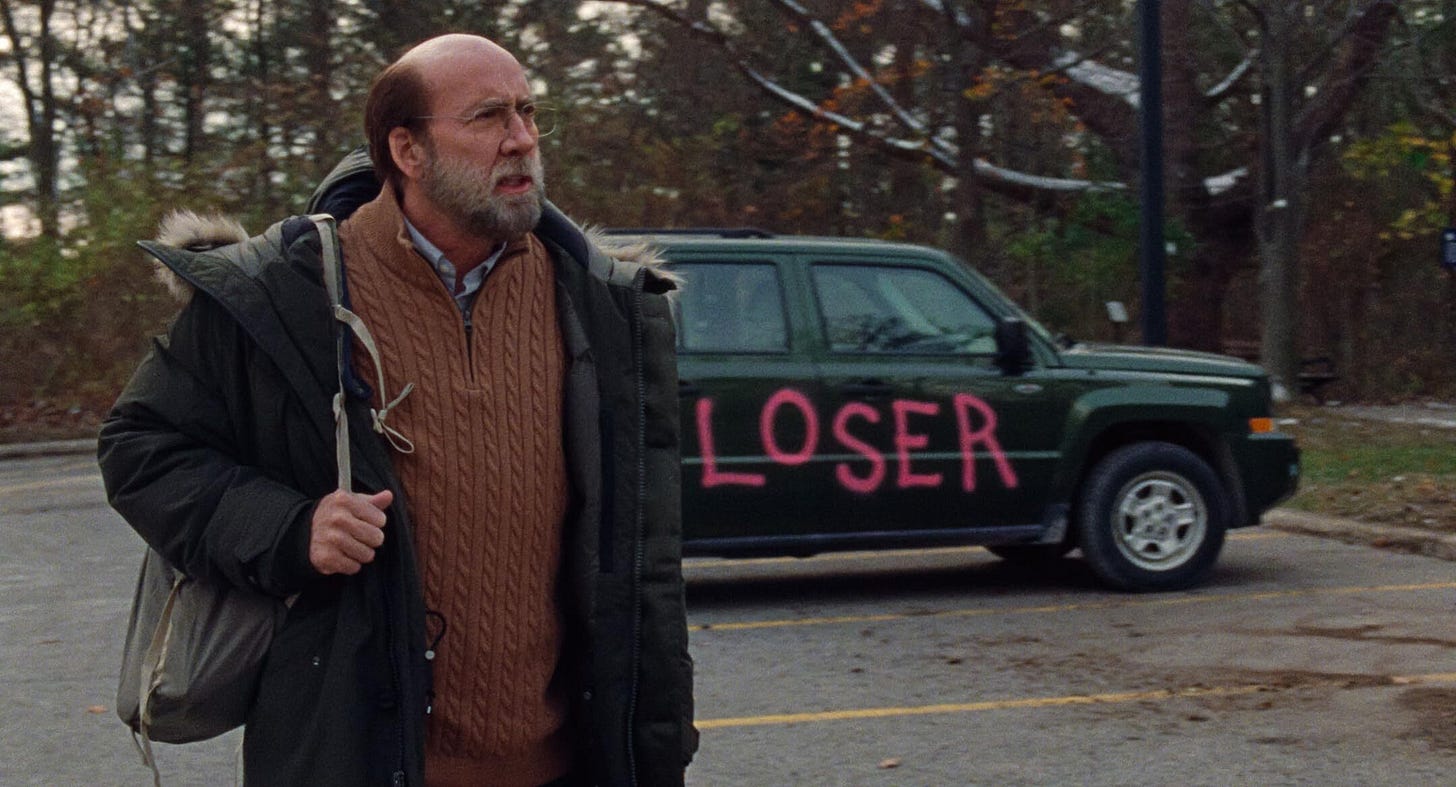

Consider Paul Matthews (Nicolas Cage). Matthews lives in what can only be considered to be radical comfort: A professor at a midsize liberal arts school with a wife, Janet (Julianne Nicholson), who also works full time, Paul lives in a large multistory home with their two beautiful daughters, Sophie (Lily Bird) and Hannah (Jessica Clement). On one level, he really does kind of have it all.

Except for one thing: respect. The respect of others—he reacts with wheedling desperation when he believes a long-ago schoolmate plans on publishing a paper that he believes he deserves credit for and then with aggrieved annoyance that another longtime friend has never invited him to his salon-style dinners—but also self-respect. When he learns that his tween daughter, Sophie, dreamed about him and that, in this dream, he did nothing when she floated away, likely to her death, his annoyance at his own inaction reflects a deep self-loathing. He’s mad at his dream self despite the fact that neither he nor Sophie has any control over how Dream Paul acts.

That lack of control is going to get much worse for Paul. At first, he’s exasperated that he’s started turning up in everyone’s dreams but is nothing more than an onlooker, a bystander while the dreams unfurl. He does nothing to help or to hurt. He’s just . . . there. Part of the background. He wants to be in the on the action. Again, it’s a case of not knowing how good he has it: Like many of us, Paul yearns for the spotlight but doesn’t understand what the spotlight entails. He thinks his newfound viral fame will allow him to find a publisher for his book on evolutionary biology. When he goes to a marketing firm headed up by Trent (Michael Cera), he finds out that the best they can do is make him a Sprite pitchman.

Paul’s annoyance at being background fodder turns to horror when his dream avatars start attacking the dreamers. All of a sudden, he’s gone from a curiosity to a subject of loathing: his students accuse him of inflicting trauma on them and want him fired; his wife is taken off a project she had been excited to work on; his daughters become the subject of teasing at school. His mere presence provokes tears. The society-imposed isolation and exile is Kafkaesque: Paul has done nothing wrong, yet finds himself in social prison.

Again, the metaphor for being canceled is neither subtle nor intended to be; in a way, Dream Scenario is a little like a movie-length version of the Milkshake Duck tweet: “The whole internet loves Milkshake Duck, a lovely duck that drinks milkshakes! *5 seconds later* We regret to inform you the duck is racist.” Stretching that 139-character conceit into a 100-minute movie wears it a little thin. But Dream Scenario is at its most poignant in the pathos of Nicolas Cage’s performance. His Paul is both somewhat sympathetic—how could he not be after falling into the Charlie Kaufman-esque nightmare of society’s collective unconscious?—and, frankly, deeply unlikable. He is a narcissistic nebbish, pathetic in a way that’s neither charming nor sympathetic. A hulking, lumbering Woody Allen but without the nerdy charisma. He demands acknowledgment for things he hasn’t done and he longs to be included in social settings despite lacking basic social graces. He feels he’s owed, and few archetypes are more aggravating than the guy who thinks he’s owed something he isn’t.

Still, writer-director Kristoffer Borgli’s portrait of a schlub ground up by the gears of modern social madness is amusing and occasionally cuts deep. In an intriguing artistic convergence, the Norwegian Borgli joins the Swedish Ruben Östlund (The Square, Triangle of Sadness) and the Dutch Halina Reijn (Bodies Bodies Bodies) as the most incisive critics of the pathologies of modern culture, particularly a specific brand of modern American internet culture. Distance is a jaundiced eye’s greatest ally; perhaps it allows this trio of Northern European directors to see modernity’s absurdity for what it is.