The FBI Spent a Generation Relearning How to Catch Spies. Then Came Kash Patel.

As China’s spies grow more aggressive, the FBI is distracted and off-balance.

AMERICA HAD BEEN AT WAR FOR TWO WEEKS but didn’t know it. The onslaught began with a fleet of store-bought drones swarming a power substation in Pennsylvania, delivering explosives made from common chemicals. They shredded switchgear and control systems, cutting power to airports, hospitals, and nearly half a million homes.

Hours later, a far-right extremist group calling itself “Dark Reich” took credit for the attack in an anonymous video replete with Nazi and occult symbols. The group hailed the blackout as the opening salvo of a campaign to bring down the U.S. government. They urged others to replicate their efforts and ignite a race war.

Over the next few days, copycat attacks cut the power for hundreds of thousands of Americans as summer temperatures soared into the 90s. Nobody could figure out who was piloting the drones. Each incident looked amateurish, yet the pattern worried FBI officials. Bureau investigators began to suspect a foreign adversary might be quietly orchestrating “gray-zone” attacks—covert strikes that offered plausible deniability.

Soon anonymous cyberattacks compounded the damage, crippling municipal governments, water systems, and first-responder networks from Atlanta to Denver. Rail corridors and ports—critical for stocking grocery stores and mobilizing the military—snarled in the digital gridlock. In an already toxic political climate, the White House was unable to craft a coherent response. Two weeks into the crisis, the source of the chaos became clear when China launched a swift and decisive invasion of Taiwan, and the United States was too paralyzed by domestic strife to stop it.

This scenario—hypothetical, but based on very real fears—is laid out in a 2024 RAND Corporation study modeling how America’s enemies could mask state-directed attacks as the work of extremists or criminal groups. Carrying out an operation of this magnitude on American soil would require a sophisticated network of spies. Which is exactly what China’s security services have been building since the late 1970s, stealing vital military, nuclear, and technological secrets en masse.

Recently, Beijing’s intelligence services have gotten more aggressive. They’ve activated clandestine networks to organize violent crackdowns inside the United States, kidnapped American citizens, and carried out sweeping cyberattacks that hit everything from telecom giants to military IT networks. Some security researchers have speculated that, in a crisis, China’s espionage networks could quickly be repurposed for sabotage.

American security experts fear that growing networks of foreign spies, combined with new technology, represent an unprecedented threat—one the FBI, the primary agency tasked with thwarting hostile foreign intelligence services, may struggle to address.

“Look at what the Ukrainians are doing with drones and AI against Russia,” says national-security analyst Paul Joyal. “I know our adversaries are watching.”

Yet as these dangers have mounted, the White House has proposed slashing the FBI’s budget by more than $500 million and has shifted the bureau’s priorities away from combating spies and other forms of foreign influence. Under Director Kash Patel, the FBI has moved people and power out of the bureau’s headquarters in the J. Edgar Hoover Building in Washington and into the heartland. He reassigned nearly a quarter of all agents to a job that’s never been part of the FBI’s purview, immigration enforcement, according to data obtained from the bureau by Virginia Sen. Mark Warner, a Democrat. Counterintelligence specialists with deep expertise in countries like China, Russia, and Iran are now regularly working immigration cases on a rotating basis, according to former agents who recently left the bureau. The FBI has also limited investigations of crimes like violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), allowing foreign spies greater room to maneuver.

The end result of these changes, former senior FBI officials maintain, is that America is extremely vulnerable—not just to an attack, but to an unprecedented level of foreign espionage.

“It’s a disaster,” says Robert Anderson, the head of FBI counterintelligence from 2012 to 2014. “I’m rooting for everybody because we’re all Americans, [but] Patel needs to wake up.”

In a statement, the FBI said it was working with agencies across the government, publicly highlighting the tactics of America’s adversaries, and actively trying to change government policies to allow it to better protect the United States. “Looking towards the future,” a bureau spokesperson said, “we are preparing for the impact new technologies such as Quantum and AI will have on counterintelligence threats.”

But some lawmakers already seem to have lost faith in the bureau’s approach. In Washington, the House Intelligence Committee, led by Arkansas Republican Rep. Rick Crawford, recently approved a bill that would overhaul counterintelligence, stripping the FBI of its leading role. “The counterintelligence threat is very real,” said a spokesperson for the committee. “This is not politics; this is about national security and the safety of Americans in the homeland. The light is flashing red.”

The FBI is the country’s chief counterintelligence agency and premier law enforcement organization. If the bill were to become law, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard would be put in charge of all U.S. counterintelligence efforts, including the FBI’s spy hunters. Her office is currently responsible for making sure the eighteen agencies in the U.S. intelligence community—including the FBI—work together and share information. Critics warn that expanding Gabbard’s role could harm civil liberties by shifting some of the bureau’s counterintelligence decision-making outside of the Department of Justice, a law-enforcement institution bound by constitutional safeguards. “That’s really dangerous,” says Frank Montoya Jr., a retired FBI agent who was once the head of counterintelligence for the agency Gabbard now runs. “You could be creating a domestic spy agency with even less transparency to the American public.”

A House Intelligence Committee spokesperson disagreed, adding that the bureau would not lose the power to carry out its own investigations. “This effort,” the spokesperson said, “is about bringing all of the tools to the table—not degrading any, FBI or otherwise.”

It’s not the first time the bureau’s counterintelligence agents have faced such a flashpoint. More than two decades ago, as then-FBI Director Robert Mueller began diverting resources to combat terrorism in the wake of the attacks on September 11th, the bureau’s counterspies were reeling from a series of espionage disasters, post–Cold War budget cuts, and pressure from Congress to strip the FBI of its counterintelligence mission. Meanwhile, the threat from Chinese espionage was exploding. Beijing not only employed intelligence officers to steal secrets; it began coercing tens of thousands of Chinese students, tourists, and businesspeople to help them in an “all of society” approach to spying.

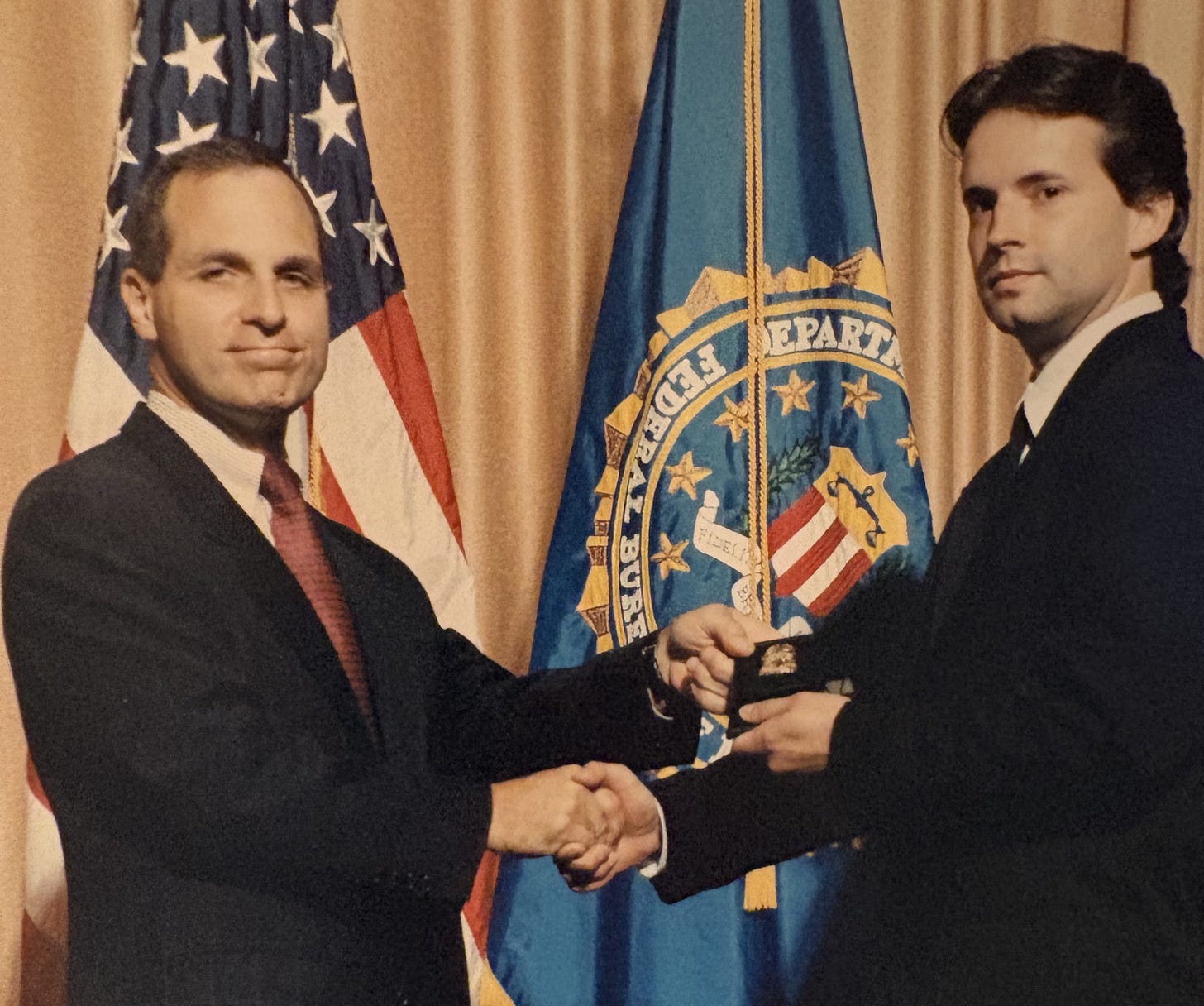

The bureau was incapable of combating this onslaught until a small group of veteran FBI spy hunters, led by Assistant Director David Szady, shifted its strategy in 2002. Instead of simply hunting spies who had infiltrated the government and the private sector, the bureau used preemptive tactics—blocking or trapping foreign agents before they could do damage. To succeed, they had to confront scandals involving sex, spying, stolen nuclear secrets, and an FBI culture in which, as Szady puts it, only “cigar-smoking, beer-drinking, door-kicking agents” in the criminal divisions won respect—and got the funding that went with it.

Today, however, Patel and President Donald Trump are moving toward an earlier strategy—one that failed spectacularly in the early 1990s, according to former senior spy hunters. Back then, Director Louis Freeh, believing a decentralized approach would be more effective at fighting crime, “took a sledgehammer instead of a scalpel to headquarters staffing,” says Thomas McWeeney, a contractor the FBI hired at the time. But instead of welcoming a new era of effectiveness, Freeh oversaw a decade marked by crises—from intelligence failures leading up to the September 11th terror attacks to the bungled espionage investigation of Dr. Wen Ho Lee.

In a series of exclusive interviews, Szady, McWeeney, and other former FBI officials recounted their successes and failures as they tried to rebuild the bureau’s Cold War–era spy-hunting capabilities—a process laid out in a 2005 internal FBI document obtained by The Bulwark. Many of these former bureau officials, including lifelong Republicans and Trump supporters, say they share Patel’s stated goal of “depoliticizing” the FBI. But some worry the administration is ignoring—or worse, actively crippling—counterintelligence at a critical time, as adversaries experiment with grave new threats, from AI-driven weapons to advanced cyber intrusions. Their experiences offer a glimpse into the type of challenges Patel faces—not only from foreign adversaries like China, but from rivals like Gabbard. “It’s tragic,” says Montoya. “All our work is being destroyed.”

‘They’re going to eat you alive’

IN LATE SEPTEMBER 2001, BARELY TWO WEEKS after al Qaeda operatives murdered 2,977 Americans, Robert Mueller sat in the bureau’s massive “war room” overseeing hundreds of agents trying to hunt down those responsible for the attacks. Despite the counterterrorism whirlwind, Mueller—less than a month into his service as FBI director—still had to figure out how to juggle the bureau’s other responsibilities, including fighting crime, rooting out corruption, and thwarting foreign spies.

That afternoon, Mueller tore himself away to meet two veteran spy hunters—Szady and his chief of staff, Kevin Favreau—in a vestibule adjacent to the war room. Spying had changed a lot since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Computer and internet technologies were booming and ascendant powers like China were aggressively targeting the United States. Earlier that year, President George W. Bush had put Szady in charge of a new interagency organization called the National Counterintelligence Executive (NCIX). It was formed to help the FBI, CIA, and Department of Defense coordinate their responses to emerging threats from foreign spies. Mueller wanted to better understand how it worked, Szady recalls. He closed the door, sealing the three men off from the cacophony of the command center, and asked: “What is your definition of counterintelligence?”

For Szady and Favreau, the subtext was hard to miss. During their frequent trips to Capitol Hill, they’d heard that legislators and staffers had come to see the FBI’s approach to both counterterrorism and counterintelligence as antiquated and inept. Szady, a charismatic showman with a staccato New England accent, had a reputation for being brash, even coarse at times. But he chose his words carefully, framing counterintelligence as a wide range of strategic and tactical moves to disrupt foreign spies.

“Wrong,” Mueller said, interrupting Szady. “It’s about espionage, espionage, espionage.”

The FBI director’s meaning was clear—he wanted stats he could show to Congress: criminal prosecutions and spies behind bars.

“Director, that may be your opinion,” Szady replied, “but if you go up on Capitol Hill and tell them that, they’re going to eat you alive.”

Mueller seemed shocked by Szady’s blunt answer. With Lower Manhattan and the Pentagon still smoldering, he cut the meeting short after fifteen minutes. But he followed up in a series of talks with Szady that fall.

“Mueller,” Favreau recalls, “had no background in [counterintelligence].” Szady, however, had spent decades at the FBI chasing traitors like John Walker—whose spy ring handed Moscow potentially war-winning Navy secrets—and thwarting espionage aimed at Silicon Valley. He wasn’t afraid to tell Mueller that, despite some sporadic successes, the FBI’s counterintelligence program had largely become the “bastard child of the bureau” in the 1990s.

(Mueller could not be reached for comment for this story.)

The FBI’s counterintelligence program had largely become the “bastard child of the bureau” in the 1990s.

By the turn of the century, morale had cratered among FBI spy hunters. “Counterintelligence was considered the rubber gun squad in some offices,” says Montoya. “It was where you put the guys you couldn’t use anywhere else.” The treachery of FBI-agent-turned-Russian-mole Robert Hanssen had also tainted the bureau at a time when its Cold War–era, one-on-one approach to spy-hunting was becoming obsolete. Globalization had changed the rules. America’s rivals—and sometimes even its allies—now waged what officials call “asymmetric espionage,” exploiting the open nature of American society to steal secrets through front companies, academic exchanges, cyber intrusions, and other nontraditional means. China led the way, targeting American technology and know-how in an all-out drive to catch up with the West.

Traditionally, spy services rely on a small cadre of intelligence officers operating abroad. But Beijing relentlessly recruited thousands of collectors from all parts of its society—scientists in sensitive labs, businesspeople, and visitors on student and tourist visas.

They sent “multiple threats in multiple waves and different disguises,” says Rudy Guerin, a former head of the bureau’s China section. The vast majority of the people coming into the United States from China never engaged in espionage. But Beijing’s aggressive deployment of potential spies left the FBI outnumbered by tens of thousands to one. Each Chinese asset might return only a sliver of data, but when assembled in Beijing, the fragments formed a detailed mosaic of U.S. capabilities—an approach described by experts as a “thousand grains of sand.” It’s a numbers game that played out all across the country. “Where you find a McDonald’s,” Szady says, “you’ll find a Chinese spy.”

These challenges were among the forces that pushed Congress as well as the White House to create NCIX, which would ultimately be folded into the National Counterintelligence and Security Center. But from the moment Szady was put in charge of it, the CIA had resisted giving his team the authority they needed. Then September 11th and the War on Terror consumed the government.

In November 2001, two months after their first meeting, Mueller decided to bring Szady back to the bureau. He wanted him to lead counterintelligence and push through the ideas that had stagnated at NCIX.

What neither Mueller nor Szady knew at the time was that the FBI’s inability to stop Chinese spies was about to become part of a much bigger battle on Capitol Hill. Lawmakers, furious over pre–September 11th failures and alarmed by serious breaches of U.S. nuclear secrets, would openly threaten to strip the bureau of its counterintelligence responsibilities altogether.

‘Broken at every possible level’

WHEN SZADY RETURNED TO THE FBI to rebuild the counterintelligence program, one name immediately came to mind: Tom McWeeney, his “consigliere” at NCIX, and a longtime contractor at the bureau. McWeeney never set out to work in law enforcement. As a broke 24-year-old Georgetown grad student in the early 1970s, he had landed a job as a chauffeur for Drug Enforcement Administration executives. At the time, Congress was harrowing the DEA over a string of bribery, money-laundering, and corruption scandals. Affable and disarming, with a knack for deciphering people and situations, McWeeney earned the trust of the agency leaders he drove around. He eventually landed a job helping the DEA comply with freedom-of-information laws and later shaping the agency’s response to drug cartels in the 1980s.

After leaving the DEA in 1992, McWeeney reinvented himself as a strategic planner. “Most people would rather chew tinfoil than have anything to do with the words ‘planning’ or ‘government,’” he liked to joke. But his approach stood out because he insisted that agencies avoid the temptation to chase empty stats. Instead, McWeeney demanded brutal honesty in measuring success and insisted on delivering real, consequential outcomes.

By 1997, McWeeney had become something of a guru in D.C., giving seminars that packed rooms. He eventually caught the attention of the FBI’s newly appointed deputy director, Robert “Bear” Bryant, who had inherited an organization that was, as McWeeney puts it, “broken at every possible level.”

Many of the bureau’s issues originated when Freeh, a tenacious former-agent-turned-judge, took over in 1993. He immediately set out to return the FBI to its roots chasing criminals. He saw bureaucracy as a disease and distrusted technology at a time when computers and the internet were becoming more important to people’s daily lives. Within months of becoming director, Freeh had nearly wiped out the headquarters supervisory staff the bureau relied on to coordinate cases, sending the vast majority of them out to work street investigations. Some former FBI officials say the impulse was good—“He was trying to get rid of dead wood,” as one former senior bureau official puts it. But he went too far, McWeeney says, neutering the Hoover Building’s power to guide complex cases. Like Patel, he wanted to shift the bulk of the FBI’s investigative power from the headquarters to the field offices. (Freeh did not respond to a request for comment for this article.)

The result of Freeh’s changes, McWeeney says, was gridlock. The intricate demands of chasing spies and terrorists frequently require collaboration across multiple FBI field offices, large-scale coordination of surveillance, and cooperation with outside agencies. Freeh’s purge meant day-to-day work lagged behind, further snarling operations.

Perhaps most egregiously, in 1995 a source walked into a CIA station in Taiwan with a trove of Chinese government documents. Among them was what appeared to be designs for a weapon strikingly similar to the W88, the United States’ most advanced thermonuclear warhead. It signaled potentially the worst theft of sensitive nuclear secrets since the ones that helped the Soviets acquire the atomic bomb. Yet the investigation—codenamed “Kindred Spirit”—sputtered from the start, andFreeh’s decentralized FBI was a major culprit. When headquarters sent agents out to New Mexico’s Los Alamos National Laboratory to figure out what had happened, local supervisors in Albuquerque pulled them away to chase what they considered more pressing issues involving gangs, fugitives, and crimes on tribal lands. Despite the gravity of the alleged theft, counterintelligence ranked only fourth in the Albuquerque field office’s workload. The case dragged on for years without an arrest.

Before ascending to the bureau’s second-highest post, Bear Bryant had served in the FBI for decades. He oversaw investigations into the Oklahoma City bombing and the arrest of notorious spy Aldrich Ames. He wasn’t about to let the bureau’s legacy—or his own—become permanently tarnished. So he hired McWeeney to help fix what was broken.

In 1998, Bryant and McWeeney worked with a cadre of senior experts and came up with a plan. It involved reestablishing FBI headquarters as the bureau’s central authority for coordinating the field offices, along with better intelligence sharing for both criminal and national-security matters. It also included something the FBI had never attempted: trying to foil plots and attacks before they began. Though much of their work was aimed at reversing the effects of Freeh’s changes, the director—once briefed on their proposal—became an ardent supporter, McWeeney says. Freeh shifted from a primarily criminal focus to championing the FBI’s national-security mission. (Bryant did not respond to a request for comment.)

In 1995 a source walked into a CIA station in Taiwan with a trove of Chinese government documents. Among them was what appeared to be designs for a weapon strikingly similar to the W88, the United States’ most advanced thermonuclear warhead.

Implementing Bryant’s vision took on new urgency that year as al Qaeda operatives carried out deadly attacks against American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. After Bryant retired the following year, McWeeney stayed to refine a more detailed blueprint for fighting terror. At first, the incoming Bush administration refused to fund it. Instead, they prioritized crimes involving drugs and firearms. That quickly changed after the September 11th attacks, when the War on Terror became the bureau’s top priority and the Justice Department adopted the ideas that McWeeney and Bryant had advocated years earlier—without their names attached.

The history of the bureau’s counterterrorism transformation after September 11th is well known. What’s often overlooked is that, at roughly the same time, the FBI also reinvigorated its counterintelligence program, which had been plagued by embarrassments in the late 1990s.

In May 1999, a report by the Cox Committee claimed that Chinese spies had stolen key information about seven U.S. nuclear warheads and a staggering range of missile and guidance technologies. Scientists at Stanford disputed some of the report’s more sweeping findings, but later government reports upheld the core premise. “The Chinese theft of nuclear weapons technology . . . has advanced the threat to our nation by a generation,” Steve Chabot, a Republican congressman from Ohio, said on the House floor at the time.

McWeeney, Bryant, and their team had attempted to reverse the dysfunction with their plan—elevating counterintelligence to a nationwide priority for the bureau. But vital leads in the Chinese nuclear spying case had already gone stale, while both the FBI and Department of Energy officials ignored opportunities to tighten security. At the same time, political leaders from both parties blamed the Clinton White House—which was focused on deepening trade ties with Beijing—for failing to act with more urgency.

In 1999, the bureau arrested Dr. Wen Ho Lee, a Taiwanese-born scientist at Los Alamos with access to classified information related to the W88. The leak they traced to him was just one sliver of the broader nuclear-weapons losses detailed in the Cox Report. But without solid evidence, even that case quickly unraveled. Investigators leaked his name to the media, mishandled evidence, and overreached on charges they couldn’t prove. Lee’s lawyers also made use of “graymail,” the tactic of forcing prosecutors to drop charges rather than risk exposing secrets in open court. In 2000, Lee claimed the government racially profiled him and pleaded guilty to a single count of mishandling classified information. As he put it in his book, My Country Versus Me: “Had I not been Chinese I never would have been accused of espionage.”

The United States has a long history of alarmist and racist treatment of Asian immigrants and American citizens of Asian descent. But the failure in this case, according to former FBI officials, was structural. Because of the lack of oversight at headquarters—an arrangement critics warn Patel is bringing back—the bureau had lost the initiative to determine who, or how many people, had actually spied for China at the nuclear labs. Michael Rochford, who later became the FBI’s first counterespionage section chief under Szady, helped conduct the postmortem on “Kindred Spirit” and the wider losses identified by the Cox Report. His conclusion: Thousands of individuals might have been responsible for the breaches, which made pinning down the culprits nearly impossible.

Spies hidden in plains states

SO HOW DO YOU STOP hundreds of thousands of spies—not only from China, but from Russia, Iran, Israel, and others—all targeting America, both for military secrets and economic espionage? Even if tracking all the potential spies were logistically possible, it would entail mass surveillance and a gross violation of civil rights. The solution was to identify the things thieves were targeting and build moats around them. Instead of hunting spies—as they had during the Cold War—the FBI would need to find ways to block or trap them.

For Szady’s team, the idea wasn’t new. It had grown out of the economic-espionage initiatives the bureau launched in the early 1990s. Szady had worked on some of them in the FBI’s Silicon Valley office while helping to protect America’s tech sector during that period. And those same ideas formed the core of what the White House later tasked him to develop at NCIX with Favreau and McWeeney. But now that they were back at the bureau, they’d need to tackle the hard part: execution.

In the early months of 2002, the team launched a flurry of whiteboard sessions by day and gatherings at a cigar bar by night (Szady called these latter meetings “vespers”) to hammer the ideas into a plan for the field offices. During that time period, McWeeney was leading a brainstorming session at the FBI’s training academy in Quantico, Virginia with a group of field agents. They bandied around ideas about resources, money, and experience, but struggled to articulate the essence of the new strategy. Then a voice from the back blurted out, “You have to know your damn domain.” McWeeney knew that was it—the idea stuck. Eventually Szady would distill it further: “Know your domain”—three words that would define the FBI’s new playbook for stopping spies.

That playbook, according to the 2005 internal FBI document obtained by The Bulwark, involved proactively identifying and protecting what Chinese spies were looking for. “What are all the Chinese nationals doing in North Dakota?” Szady throws out as an example. The regional field office at the time could only shrug—they didn’t know their domain. North Dakota wasn’t a tourist destination. But it was home to U.S. early-warning radar systems tied to NORAD. It was also where agricultural research hubs, like North Dakota State University, were developing cutting-edge grain and biotechnology.

“The Chinese knew our domains better than we did,” says Tom Mahlik, a deputy assistant director for the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) who was later detailed to the FBI. Mahlik points to the Navy’s Acoustic Research Detachment, a facility on Lake Pend Oreille, a remote, glacier-carved reservoir nestled between the snowcapped peaks of Idaho’s panhandle. There, engineers test top-secret designs for submarine hulls and propulsion. These are the kinds of technologies that keep America’s ballistic missile submarines undetected and its nuclear deterrent credible. Before “know your domain” became a mantra at the bureau, the regional field office in Salt Lake City didn’t even know it was there. “But Chinese spies did,” says Mahlik, and the bureau quickly detected that many of them were traveling to Idaho. The FBI made sure researchers were aware that if a local bartender, waiter, or ski instructor showed unusual interest in their work, it might not be an innocent question.

To boost this strategy, the bureau pushed for greater cooperation with the CIA, the military, and other intelligence partners. It also prioritized what Szady, McWeeney, and Favreau dubbed “sophisticated ops.” These involved double agents, deceptions, and other missions that wouldn’t look out of place in an espionage thriller.

But the new approach hinged on the oldest discipline in the espionage trade: recruiting sources. The bureau would need to ramp up its efforts nationwide, positioning informants near suspected front companies or cultivating contacts inside Chinese student associations. Their goal was to detect if someone was secretly taking orders from Beijing.

The FBI’s new recruitment push wasn’t limited to adversaries. It also required building trusted networks at military installations, defense contractors, advanced research centers, and companies holding sensitive trade secrets. The bureau needed cooperation from managers and employees willing to act as “tripwires” to flag suspicious activities or sudden foreign interest.

The majority of this work wouldn’t lead to the arrests and statistics Mueller had put at the center of counterintelligence work during his first conversation with Szady and Favreau. But Szady and his team felt collecting intelligence was critical to their core mission: knowing the intentions of their adversaries and thwarting their plans. As Montoya, the former FBI agent, explains: “It was both common sense and revolutionary.”

‘Why the fuck aren’t you pounding on Mueller’s desk?’

BY APRIL 2002, SZADY HAD A PLAN—now he needed a solid team to carry it out. Early in his talks with Mueller, he had made his return conditional on placing people of his own choosing in key posts. Late one night at Kilroy’s, a sports bar in Northern Virginia, Szady gathered Favreau along with others from his inner circle and scribbled their names and the positions he wanted them to fill on a napkin.

A few of Szady’s picks would require a break with the way the bureau usually promotes from within. Both Rochford and Guerin had never served as assistant special agents in charge, the traditional step toward a top slot at headquarters. Some within the bureau felt that Szady had created a cliquish boys club—what the journalist Bill Gertz referred to as “the posse” in his 2006 book Enemies. But the assistant director was determined to succeed or fail on his own terms.

Many in the bureau never expected Szady himself to rise so high. McWeeney recalls that some saw him as “a good agent, and a great guy to have a beer with. But he was inappropriate, loud, and didn’t seem to understand details.” Yet behind Szady’s swagger, McWeeney observes, was an instinct for identifying solutions most others didn’t see and, more crucially, the ability to sell them.

Szady knew he couldn’t push reform from headquarters. He’d need the heads of the fifty-six field offices to drive the message home to their agents on the ground. So he and McWeeney concocted a plan: win over the biggest hard-liners from the criminal side—like Charlie Mathews, an agent who was notorious for his disdain for counterintelligence. If they did that, they hoped, everyone else would at least be willing to hear them out.

With Mueller’s blessing, Szady flew six of the bureau’s most influential special agents in charge, including Mathews, to Washington in early April 2002. Late one morning, Szady and the agents gathered with ten other staffers in a fifth-floor conference room at the Hoover Building. The room went quiet as Szady wound himself up into a pulpit-style performance. “We’re fighting terrorism because it might hit you like a heart attack, out of nowhere—‘boom’—it’ll kill you,” he began. “In reality, there’s a cancer that’s probably more serious. It’s a more certain death. It’s eating you up, bit by bit. That cancer is the intelligence threat.”

China, he explained, was surging ahead—using its vast number of spies and the open nature of American society to steal its most sensitive secrets. Beijing’s recruitment pitches often appealed to duty to the motherland, but could also involve cash, sex, or coercion. They even targeted U.S. citizens with relatives in China. Refuse to spy, and a sick family member back in Beijing might lose their job, be refused medical treatment, or worse.

Szady paused, watching the eyes in the room to make sure he still had them. “And the FBI,” he said, “is really doing nothing. Zero.”

Then he pivoted to the ways they could counter China’s numbers game. Before he could finish, Mathews’s hand shot up. Everyone stared. “Shit, here he goes,” recalls McWeeney, “we’re all waiting for him to give the zinger as to why it’s not going to work.”

But Mathews’s response wasn’t what anyone expected. “If all this bullshit you’re saying is true, Dave, then why the fuck aren’t you in there pounding on Mueller’s desk asking for more resources?”

Szady took a long pause. “You’re right,” he said. “I should be.”

(Mathews did not respond to a request for comment.)

Szady took Mathews’s advice and asked Mueller for an unprecedented transfer of 225 agents from the criminal division into counterintelligence. Every field office in the country would have a squad. He insisted on other changes as well. Counterintelligence training at Quantico shifted from three hours to three weeks. And by placing an assistant special agent in charge focused on national security in the field offices as well, the bureau forged a new career path for counterintelligence specialists to rise through the ranks.

Szady and company took their pitch around the country, but winning over partners in industry and academia was just as tough. Trade with China was lucrative, and plenty of executives worried that having the FBI poking around their operations might spook investors. Academics were no easier. The universities that anchor America’s defense and commercial research have been wary of the bureau since the days of COINTELPRO (an abbreviation of “counter-intelligence program”), a 1960s-era endeavor in which the FBI surveilled and harassed opponents of the Vietnam War and civil rights leaders, including Martin Luther King Jr. These concerns—along with fears about racial profiling—had only escalated in the wake of the Wen Ho Lee affair.

To overcome the resistance, the bureau launched a massive outreach effort that would continue for years. It included forging strategic alliances with business leaders and the heads of major universities.

The new counterintelligence program was a hard sell on Capitol Hill, too. And it was about to get a lot harder. An espionage scandal was about to explode in Los Angeles—one that involved a prized FBI informant who was secretly sleeping with two of her handlers and allegedly spying for Beijing.

Sex, lies, and political backlash

ON APRIL 9, 2003, WHILE THE WORLD was fixated on the collapse of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq, FBI agents raided two homes in Los Angeles. The targets were James “J.J.” Smith, a recently retired senior counterintelligence agent for the bureau, and Katrina Leung, codenamed “Parlor Maid,” an informant prized for her deep connections inside Beijing’s byzantine power circles. The FBI now suspected her of being a double agent.

For Steve Conley—Smith’s friend, protégé, and eventual successor on the Leung case—the scandal was personal. When Smith retired in late 2000, he urged Conley to take over Leung’s operations, telling him his asset would “make his career.” Instead, Conley immediately saw warning signs: Leung had unreported travel to China, access to sensitive FBI secrets, and an unsettling familiarity with Smith. Conley tried to raise his concerns with his superiors, but they brushed him off.

Conley continued to push until December 2001. That’s when investigators working on a secret task force looking into Leung pulled Conley aside and told him what was really going on. They recruited him to help. Shortly afterwards, the FBI discovered it had not one but two espionage suspects, when surveillance in a hotel room in Los Angeles caught Smith and Leung in flagrante delicto. “They had the video,” Conley recalls. “They didn’t make me watch it, but . . . they said,‘This means [Smith is] compromised.” It became clear that Smith, Leung’s handler, had been secretly having an affair with her for nearly twenty years, through most of her spying career. Their sexual liaison threatened to undermine the bureau’s entire China program.

Conley’s new mission was to quietly determine what his former boss had passed to Leung. In 2002, Les Wiser, the agent who led the squad that captured notorious spy Aldrich Ames, took over the task force. They discovered the duo had blown a wide swath of bureau operations. “[Smith] was the supervisor,” Conley explains. “He had access to all of the China cases including joint operations. . . . People were told on the squad, ‘Run your stuff by J.J., run it by Parlor Maid.’ That meant she saw everything,” says Conley. This included the FBI’s investigations into U.S. nuclear leaks: “She could let [her handlers] know back in Beijing and they could warn their source, their spy in the lab: ‘You need to stop, you need to lay low, or you need to get out.’”

The potential implications of the Leung case were staggering. It meant twenty years of FBI investigations into the loss of U.S. nuclear secrets may have been sabotaged from the inside. Though the “Parlor Maid” fiasco started long before Szady’s tenure, Mueller came down hard on him to make sure the FBI’s other sources were better vetted. “It was a fucking earthquake,” says Rochford. Guerin and his team dove into the files of assets all around the country to weed out other potential problems, kicking off a new push to validate their sources. But the scandal was already doing damage to the bureau’s reputation in Washington. Especially after Wiser’s team uncovered that Leung simultaneously carried on a twelve-year affair with William Cleveland, another senior FBI counterintelligence official. He too had played a key role in investigations into Chinese spying at U.S. nuclear labs. (Cleveland could not be reached for comment.)

Despite serious espionage allegations, Leung only pleaded guilty to tax-evasion charges. “They followed me for two years, recorded 40,000 minutes of phone calls, and found not a shred of evidence [of spying for China],” Leung wrote in a statement published in the Chinese-language diaspora newspaper, the China Press. Conley and Wiser maintain that graymail was a major factor in the government’s case unraveling. Regardless, the task force finally neutralized what Conley calls “the biggest penetration of the FBI by the Chinese—certainly that I know of.” (Smith and Leung did not respond to requests for comment.)

In the early summer of 2003, as criticism of the bureau intensified in Washington in the aftermath of the “Parlor Maid” scandal, the Economist published an article titled “America Needs More Spies,” calling for a new domestic intelligence service separate from the FBI. Among its six authors was Bryant, the former deputy director who had been McWeeney’s ally in pushing for reform, who had since retired. Szady felt blindsided. He was surprised that someone who’d worked so hard at changing the bureau would reach those conclusions.

It would only get worse for the FBI. Later that summer, the Bush administration appointed Michelle Van Cleave as national counterintelligence executive, the interagency post Szady had once held before September 11th. Van Cleave wanted to be in charge of American counterintelligence, trumping the bureau’s authority—the same reorganization recently approved by the House Intelligence Committee. (Van Cleave did not respond to a request for comment.)

The power struggle was unfolding as leaders in Washington were trying to figure out how to combat terrorism in the twenty-first century—and they were excoriating the FBI. In 2004, the 9/11 Commission said the bureau still wasn’t using intelligence in a manner sophisticated enough to fight terrorism and espionage. “We woke up and realized we had a Cold War national security apparatus in place, and that’s why nearly 3,000 people were just killed in New York,” says a senior Senate staffer who took part in the debates and asked for anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter.

Counterintelligence was just one part of this larger battle, the senior staffer adds. Senate Intelligence Chairman Pat Roberts, a Republican from Kansas, for instance, floated proposals to create a new domestic security agency similar to Britain’s MI5. In an interview with The Bulwark, former national security official Richard Clarke says the Bush administration was considering creating an MI5-style agency as well. “Bush said, ‘We’ll give [the FBI] one last chance,’” Clarke recalls.

To arm themselves for the long-running battles behind closed doors on Capitol Hill, Mueller, Szady, and other bureau officials met with the domestic intelligence services of other countries that operated without the FBI’s law-enforcement powers. What they found surprised them. Former Deputy Director John Pistole recalls how some MI5 officials wished their service and Scotland Yard were unified in the way the bureau was. The FBI’s ability to arrest, subpoena, and seize evidence, they said, gave it leverage to disrupt spy networks that those agencies salivated over. Those tools could be used creatively too, similar to how the bureau and Justice Department brought tax-evasion charges to ultimately bring down Al Capone.

In their briefings to Congress, Szady and his team also stressed that keeping counterintelligence at the FBI would help protect civil rights. The bureau had, of course, blatantly violated the law during its hundred-year history—from the Palmer Raids against suspected leftist radicals that began in 1919 when the FBI was still called the Bureau of Investigation to COINTELPRO in the 1960s. But the FBI’s obligation to support prosecutions had helped keep it tethered to the Constitution.

As they continued to speak to congressional leaders and their aides, Szady and others eventually began to make headway. Some genuinely liked their ideas and saw them making progress, the senior Senate staffer says. Others liked them just enough to preserve the status quo and avoid the hassle of aggressively reconfiguring counterintelligence.

But the FBI would still need to prove it had shaken off the dysfunction that had plagued the nuclear lab cases and others.

Soccer cleats and secret submarines

ON A SWELTERING NIGHT IN LATE JUNE 2004, faint red flashlights flitted through the darkness inside a modest midcentury home in Downey, a Southern California suburb where defense contractors have clustered since World War II. The home belonged to Chi Mak, an electrical engineer who specialized in naval propulsion systems. The FBI suspected he had another job—as a spy passing highly classified details about the Navy’s next generation of submarines and other warships to China. Now, a team of black-clad FBI agents were searching his house, taking pains to leave every item, from computers to dust-covered papers, exactly as they’d found them.

Weeks earlier, investigators had confirmed that Mak and his wife, Rebecca, would be out of town on a week-long Alaska cruise—a rare opening that gave the bureau its best chance to get inside undetected. For weeks, the lead investigator on the case, Special Agent James Gaylord, had overseen the plan. It was the first covert entry of his career, and he knew if they made a mistake, a neighbor might tip off Mak, potentially blowing the entire investigation. So far everything—from camouflaging the mobile command post in a nearby park to placing surveillance teams in the neighborhood—had gone smoothly.

Gaylord’s only oversight? Footwear. While dressing in dark clothes for the mission, he realized the only black sneakers he owned were a pair of soccer cleats he used to referee his daughters’ games. He’d covered the reflective stripes with black electrical tape, but now the cleats were digging into the soles of his feet.

After hours of searching, the agents found what they were looking for: classified schematics and propulsion data for submarines and destroyers. It was a breakthrough. These were sensitive documents that could compromise America’s advantage on the high seas.

Gaylord was excited—until he heard one of his teammates hiss through the darkness: “This house looks like it’s got fucking smallpox!” Gaylord’s cleats had left deep divots in the carpet, he writes in his new book about the case, Chasing Chi. An agent had to smooth over every single cleat mark so the couple wouldn’t suspect anything when they returned.

It was a hiccup for Gaylord in an investigation—codenamed “Glazed Stone”—that became a major win for the bureau. The case had begun in 2003, when the FBI received a tip from another intelligence agency that someone inside the company where Mak worked was leaking Navy secrets to Beijing. At first, Gaylord didn’t want the case—investigations into Chinese espionage were seen as career-enders that seldom got the support they needed.

But Gaylord and his partner at NCIS, Gunnar Newquist, reached out to headquarters for help. To their surprise, they got it—fast. Among the dozens of reforms Szady had adopted in the aftermath of the Wen Ho Lee debacle was the creation of a new team in Washington to fast-track spy cases and prevent the kind of neglect that had crippled “Kindred Spirit.” “Our job wasn’t to take control away from the field,” but to help them jumpstart the investigations, recalls Rochford, the head of that new team, known as the counterespionage section. Though the bureau’s new strategy was about stopping espionage before it started, its work with companies, universities, and other agencies meant it was also getting a lot more leads. “At any given time,” says Rochford, “we were pushing nearly eight hundred hot cases.”

Gaylord and Newquist got nearly two dozen agents, six surveillance teams, plus analysts—more than they’d asked for. And as the case moved forward, the counterespionage section occasionally worked with Gaylord’s supervisor to overrule senior managers at the local Los Angeles field office when they tried to pull people back for other work. “It was a real reversal” of what it was like dealing with headquarters before Szady, says Gaylord.

On October 28, 2005, the FBI arrested Chi Mak and five members of his family whom he had recruited to move sensitive material. Defense lawyers tried to claim the bureau’s case was driven by xenophobia. But prosecutors and agents were prepared for that line of argument—and others—that Gaylord and his cohorts say were bogus. “I’m Chinese-American,” says Sheldon Fung, an FBI case agent on the Chi Mak investigation who extensively studied the mistakes of the Wen Ho Lee affair. “There were three other Asian-Americans on the squad. We didn’t pick these people because they were Asian. . . . If any of us saw any profiling like that we’d be screaming about it.”

Two years later, a federal jury convicted Mak of illegally passing Navy secrets to China. It marked the first successful U.S. prosecution of a major Chinese spy since 1985. “The Chi Mak case,” says Fung, “set a different standard for how all Chinese cases were handled after that.”

Some of the evidence Gaylord’s team gathered led directly to more espionage arrests. And a postmortem of the case uncovered the way Chinese spies operated. Exposing their tradecraft helped the bureau—as part of its new domain program—alert other companies about early warning signs of espionage.

Equally important: The case gave the FBI a success story to help reassure Congress.

‘We’ve put a disaster in play’

BACK IN LATE 2002, NOT LONG AFTER the bureau’s new counterintelligence plan went into effect, the FBI asked Montoya to move from headquarters and become a field supervisor in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A former criminal investigator who had worked gang cases and bank robberies before he began chasing spies, he was eager to do so. “I had been baptized in the waters of Szady,” he says. “They wanted me to go out there and evangelize the program.” His supervisor at the time expressed skepticism. “If this is really a priority,” Montoya recalls him saying, “then go out and find the spies in Wisconsin.”

Montoya did just that. In less than two years, he partnered with a Wausau, Wisconsin company selling carbon fiber tubing abroad—and attracting the attention of Chinese and Iranian spies. The bureau worked with the company to set up tripwires to warn them about any suspicious purchases. He also helped crack a major case in Manitowoc, a small town on Lake Michigan. The bureau used a court-authorized wiretap to nab Wen Ning, a former Chinese consulate employee-turned-FBI informant who was playing a double game and sending Beijing computer chips for intercontinental ballistic missiles. “In the course of the investigation, we determined there was a connection between him and ‘Parlor Maid,’” says Montoya. Wen Ning was sentenced to five years in prison in 2006.

When Szady retired from the bureau that same year, he left behind not only many of the leaders he’d hand-picked, like Favreau. He also left a new generation of agents he’d helped train, like Montoya, who continued to build on what he’d started.

In the ensuing years, thanks in part to the foundation Szady and his team created, the bureau would finally come to be viewed as a respected part of the American intelligence appartus—and fully integrate cyber operations, as well. But the tension that had kicked off Szady’s and Mueller’s first conversation in the wake of September 11th never went away: How do you maintain the arduous work of developing networks of human sources when they don’t always produce the kinds of immediate stats that get Congress to pay for operations?

Subsequent FBI counterintelligence chiefs dealt with this dilemma in different ways. Robert Anderson, who held Szady’s old job between 2012 and 2014, used the domain program’s net to snare numerous potential spies, arresting them for crimes like money laundering, intellectual property theft, and FARA violations at a time when China was growing more aggressive. “It was like shooting ducks on a pond,” he says. “These are criminal violations just like bank robberies or anything else.”

Conley, who went on to become an executive in the FBI’s intelligence directorate, lamented that the program under subsequent directors seemed to lose some of its focus on cultivating long-term sources and operations. Since the first Trump administration, the counterespionage section—the team within the counterintelligence division focused on traditional spying by foreign intelligence services, as well as leaks of classified information—has been reorganized at least once. Regardless, the foundation of what Szady, McWeeney, and Favreau had pioneered stayed intact in some form. “It was mixed results, but [Szady] got results,” says Montoya.

Along the way, many of the lieutenants and agents who’d served in the program brought its strategy to corporate security consulting—an informal network that amplified the FBI’s work. Pamir Consulting, cofounded by Guerin, played an early role in detecting a breach at DuPont that led to a billion-dollar espionage case the press referred to as “stealing the color white.” The FBI took the handoff and ran an investigation that, in 2014, netted a ring of China-linked conspirators who’d tried to pilfer the secret chemical process behind the ultra-white pigment used in everything from Ford Mustangs to Oreo fillings.

Today, more than a decade has passed since the DuPont case, and the threat of foreign espionage has entered a new phase—one turbocharged by artificial intelligence. Having already created a mass-surveillance panopticon at home, Chinese officials are attempting to use their DeepSeek AI to thwart crimes, obstruct political protests, and mitigate security risks before they start—powers a recent Jamestown Foundation analysis likened to the predictive policing in the movie Minority Report.

That same unnerving capability could extend to the United States thanks to millions of Chinese-made products and services like security cameras, drones, internet-connected appliances, and even TikTok. Data from these devices and apps flow through companies obligated to report to Beijing—and its intelligence agencies. This gives China opportunities to spot weaknesses in America’s defenses—not just for spies looking to steal secrets but for covert operations aimed at both civilian and military targets.

Civil liberties guaranteed in the Constitution and American law prohibit the FBI from using similar mass-surveillance tools. But that puts the bureau at an extreme disadvantage against foreign adversaries like Beijing. “You can’t think about high castle walls keeping everything out,” says Emily Harding, a former CIA officer and Senate Intelligence Committee staffer. “You need a layered defense.”

For many security experts, the key layer is human—clandestine informants as well as partnerships similar to those Szady and his team created more than two decades ago. But instead of building on that foundation to combat new, pressing national-security challenges, Patel is shifting the bureau’s priorities to focus on deportation and street crime. In the country’s largest field offices, according to the data obtained by Sen. Warner, nearly 40 percent of agents have been assigned to immigration enforcement. The FBI says there has been a 35 percent increase in counterintelligence arrests since January.1 But many of those cases—including one earlier this month involving two men who were allegedly smuggling AI technology to China—began well before Patel became director.

Perhaps more critically, the total number of arrests doesn’t necessarily reflect the bureau’s effectiveness. “Arrests are never the measure of success,” says Rochford. “You need to know the mind of your enemy.” Putting someone behind bars rather than flipping them for information can even be counterproductive at times.

A spokesperson for the House Intelligence Committee put it even more pointedly: “Success cannot be measured by the number of indictments. Each publicized arrest demonstrates the successful identification of a system failure: hostile operatives functioned successfully within the U.S., often for years.”

Stopping adversaries like China, Rochford adds, requires gathering vast amounts of intelligence and carrying out sophisticated ops with other agencies—especially in the age of AI. These were the same metrics used by Szady and his team, reinforced by ruthless, ongoing reviews by retired counterintelligence agents, a rare form of outside scrutiny that McWeeney considered indispensable. “Patel is only paying lip service to the Chinese threat,” says Montoya. By focusing on deportations at the expense of national security, he adds, “we’ve put a disaster in play.”

Whether Patel’s goals for the bureau will impede counterintelligence work or not, William Evanina, a former FBI agent and supervisor who went on to become the director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, has stressed to lawmakers that the bureau and Congress should make sure the FBI is capable of facing the challenges of the AI era. “We do need to take a hard look at counterintelligence and how we’re protecting America,” he says. “Let’s fix things that are broken but not throw everything out that is working.”

Though some of the changes proposed in Crawford’s bill hark back to parts of Szady’s plans, others—such as elevating Gabbard—are more radical. In a memo leaked to the Atlantic in November, her office argued that counterintelligence at the bureau has become “politicized” and needs centralized control to prevent further “weaponization.” Other news outlets also reported that Gabbard was gathering support within the government for the proposal to put her in charge of all counterintelligence. The FBI pushed back, warning of the dangers of handing counterintelligence authority to an organization lacking experience with spy-hunting operations.

For now, however, Gabbard appears to have backed away from the proposed reorganization. A spokesperson for the Office of the Director of National Intelligence told The Bulwark that “DNI Gabbard supports the administration’s position, which is in opposition to the legislation.” But that could quickly change, especially if Patel—already reeling from allegations he’d misused FBI resources for his girlfriend’s personal security—becomes embroiled in more controversy that further tarnishes his and the bureau’s reputation. “We fought this battle twenty years ago,” says Szady. “Why would we waste time and energy going back to square one?”

Either way, to veterans of the post–September 11th reform battles and others, the power struggle between Patel and Gabbard felt like Groundhog Day—only worse, because the FBI still doesn’t seem to have a clear plan to confront the extraordinary threats of sophisticated foreign spies armed with advanced technology. “Any resources taken away from this just puts us more behind,” says a former FBI agent who, after years of working national security cases, recently left the bureau to avoid being reassigned to immigration enforcement. “We don’t have the luxury of time.”

Correction (December 15, 2025, 4:34 p.m. EST): A previous version of this piece stated that the FBI reported a 35 percent increase in arrests related to Chinese espionage since January. That statistic actually applies to all counterintelligence arrests, not just those linked to China.