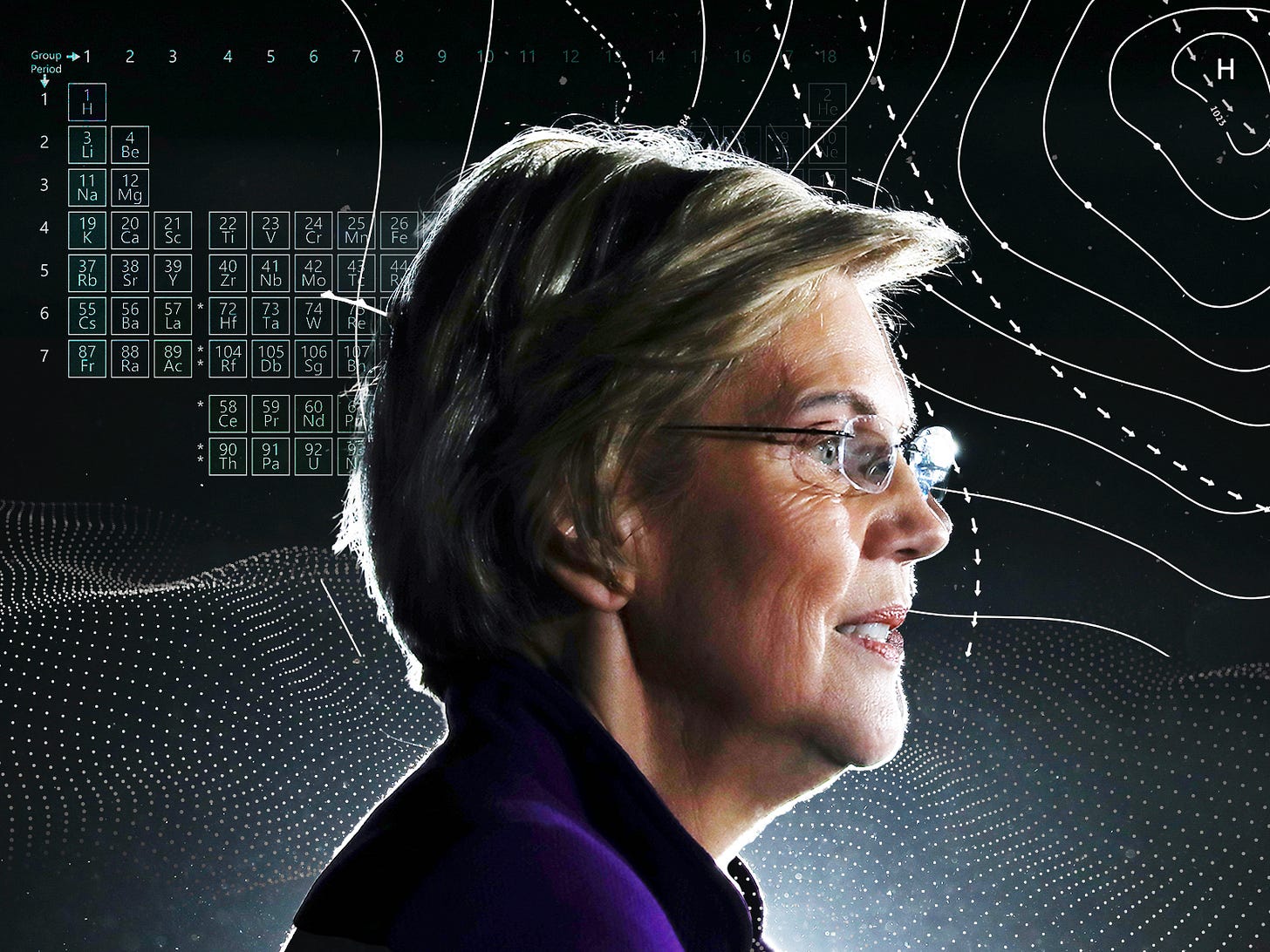

How Warren Could Win

1. The Case for Warren

I've been consistently dismissive of Elizabeth Warren's chances of winning the nomination. I have a number of reasons for thinking this and I am still quite bearish on her prospects. But Walter Shapiro is very smart and he's not so sure. He has a long profile of her over at the new New Republic:

If elected in 2020, Warren would enter the Oval Office at the age of 71 and would be the oldest newly inaugurated president in history. Despite the political culture’s frequent cruelty to older women (see Clinton, Hillary), Warren’s age is almost never mentioned by anyone—friend or foe—in the campaign. My hunch, in fact, is that if you asked Democratic voters whether Warren was closer in age to Biden (currently 76) or Kamala Harris (54), 87 percent would say “Harris,” and the other 13 percent would have “no opinion.” . . .There are two unalterable orthodoxies of politics. Every losing campaign is filled with aides peddling stories under the rubric, “If only the candidate had listened to me.” And with every winning campaign, said David Axelrod, “there is a lot of discussion that they’re inventing the wheel.” Although they may now seem like the collective outcome of a carefully executed day-by-day plan, many of the striking aspects of the Warren campaign (the blizzard of footnoted position papers; the ban on high-roller fund-raisers; and the decision to, at least temporarily, avoid hiring an outside pollster and media consultant) were fairly ad hoc and incremental. They were also, Warren watchers agree, a reflection of the candidate’s own determined and focused character. As a Warren insider put it, “There was never a Saul on the road to Damascus moment” in the campaign’s first strategy sessions. The most telling decision made at the outset was the heavy initial investment in staffers, particularly in Iowa and New Hampshire. This was not by any means a paint-by-numbers move; rival campaigns, such as those of Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg, waited until June to go on a hiring binge in Iowa. As a result, the media consensus is that Warren boasts the best ground game in the opening-gun states, which can make a significant difference in a close race. As top strategist Joe Rospars explained, “From a budgetary perspective, it’s fair to say that decisions about building your organization are because you can add media at the end. But you can’t go back and add organization.” By late July, the Warren campaign had released 29 position papers on topics ranging from banning private prisons to doubling the size of the Foreign Service. The pace of this paper chase and the level of policy detail and supporting material are unprecedented since I began covering presidential politics in 1980.

Warren is clearly having a moment. Since June she's doubled her national support. And if you wanted to make a case for why she's poised to become a front-runner, it would be the inverted yield curve. Warren's Big Change candidacy is a very hard sell in time of general prosperity. It is a much more attractive pitch in a time of anxiety and recession. It could be that the environment is changing in such a way as to become more hospitable to her candidacy. But here's the thing: Even if it is, it won't change fast enough for Warren. We are 24 weeks away from Iowa. That's it. This field is not locked in amber. Things will change. Events will intervene. Candidates will stumble and drop out. But to go from where Warren is now to the top of the pack requires not just that everything goes right for her, but that everything goes wrong for everyone else. And there are a lot of everyone's. If the race was between Biden, Bernie, and Warren—or Biden, Harris, and Warren, or Warren and any two or three other major candidates, I'd be more bullish on her prospects. But it isn't. It's a giant field with a single major frontrunner whose numbers have been durable for months, through good weather and bad. She's in a pack with a demographic thoroughbred, a personality cult, and a youth movement with tremendous candidate skills. It's not that I don't understand the political case for Warren. I do. I just don't buy it.

2. Against Joe

We had a very good piece on Monday making the progressive case for Joe Biden. I wanted to share an email from reader R.C. in which she explains why she is not on the Biden train (yet):

I have noticed how much you, rightly, admire the former vice president. In fact, sometimes the attitude towards the Democrats in general is "WHY DON'T THEY JUST CHOSE BIDEN AND MAKE THIS LONG NATIONAL NIGHTMARE END?!" which is, by the way, a totally valid reaction and opinion for anyone in the free world to hold. So, I wanted to explain where the anti-Biden sentiment is coming from within the party. I'll go further, actually, and add more context about why I think I might have specific insight on this. I worked on a Congressional race in 2018 - I was the finance director for [REDACTED]. We flipped a gerrymandered seat and won a highly contested Democratic primary in which we had all sorts of opponents from every corner of the party: Bernie supporters, union guys, single-issue candidates. This is all to say, I just went through this Democratic selection process on an infinitely smaller scale, and as a result, wanted to share what worries me about Biden:

He doesn't have the same intuitive understanding of social media that Trump has, which in 2020 is a MAJOR liability. Biden, of course, will have the best people working for him, but there's only so much a social media team can do on their own. In general, I worry a lot about Biden's seeming ineptitude with technology. Like much of the party, I'm quite young. Technology is SO MUCH a part of our lives. I'd argue it's the most important thing to my generation. So he loses points for that. Bernie (who I CANNOT stand) & Warren (she reminds me of my hippy dippy great aunt, what can I say?) are old, yes, but they are much better at least at managing a team of social media professionals than Biden.

I just want to elect a woman! For me and many of my other coastal elite bubble friends, it's impossible to imagine going into that voting booth during the primary and voting for a straight, white man. Is that fair? Absolutely not! Has the reverse been going on for as long as Democracy as existed? Yes. Does that make it okay? NO! Is gender a smart reason to vote for someone? Nope. But it's the truth. We all have our biases. I try to fight mine and often fail. I've never voted for a white man before for president!! If I am going to, Biden is a tough sell when compared to Kamala or Mayor Pete. (Though I did marry a straight white man, so I promise I'm not THAT sexist.)

I actually worry about Biden as a candidate. Without Obama, he's only ever won Delaware. That's a little scary to me. I'd prefer someone who has run and won on their own in a larger, more diverse state. We don't have a ton of data on women running for president or openly gay men running for president, but we *do* have a ton of data on Joe Biden running for president. It didn't work out!! Before JFK, everyone though an Irish Catholic couldn't win. Not a necessarily PERFECT equivalence, but it is something that worries me about Biden.

And yes, I understand that really he only needs to carry PA, WI, MI, but I grew up in PA and you can't really group the three states together. They have similarities, but also very real differences.

Lastly, Biden and his voting record are old and white while the party is increasingly young and diverse. As someone who is young and female, I naturally gravitate towards candidates who are younger and female. Most old white dudes I talk to support Biden, and they absolutely should because they see Biden as representing their interests. As 28-year-old first year law student living in New York City, I just don't see Biden even really understanding my interests. That's fine!!! It just means that when evaluating the Democratic candidates, in my little sub-culture of New York girls with our overpriced Céline bags and our rescue dogs and our mindfulness classes, we're not going to see ourselves in Biden as much as a Kamala or a Buttiegieg.

So, I hope that clears up some of the mystery as to why we haven't (yet, at least!) coalesced around Biden.

3. Evangelicals

Elizabeth Bruenig has a long piece about where evangelicals are going with Trump. It's worth your time:

Exit polls show that Trump carried 85 percent of evangelical voters here in 2016, a touch higher than the national white evangelical average of 81 percent. That in itself wasn’t surprising: For decades evangelicals have been a reliable Republican constituency. More intriguing was that a segment of white evangelicals had supported Trump all along — even during the Republican primaries, when more logical evangelical candidates, such as Texas’s own Sen. Ted Cruz, were still viable. At first, their numbers were relatively small, and ill-represented among regular churchgoers. But since coalescing in 2016, evangelical support for Trump has remained consistently high — even among regular churchgoers, who started out skeptical but now approve of Trump at rates identical to or higher than less regular attendees. White evangelicals’ electoral drift toward Trump added an element of mystery to a story that was already startling. That the thrice-wed, dirty-talking, sex-scandal-plagued businessman actually managed to win the steadfast moral support of America’s values voters, as expressed in routinely high approval ratings, posed an even stranger question: What happened? . . . That sounded familiar to Lydia Bean, 38, a researcher who taught at Baylor University and devoted her graduate sociological work at Harvard to studying the comparative politics of evangelicals in the United States and Canada. These days, Bean is a fellow with New America’s Political Reform program, where she writes and consults on political organizing and faith. When we spoke, she was gearing up to a run as a Democrat for a seat in the Texas State House. “Basically, it’s like a fortress mentality, where it’s like — the best we can do is lock up the gates and just pour boiling oil over the gates at the libs,” Bean said as we ate dinner at a tiny German restaurant near Texas Christian University in Fort Worth that night. Among evangelicals, she said, “I really think one of the things that’s changed since I did my fieldwork at the very end of the Bush administration is a rejection of politics in general as a means to advance the common good, even in a conservative vein.” In that case, politics “becomes a bloodsport, where you’re punishing and striking back at people you don’t like” without much hope of changing anything. For that kind of “hopeless cynicism” regarding politics — walls up, temporary provisions, with just enough strength and zeal left to periodically foil one’s enemies — Trump is an ideal leader.