How Zelensky Rose to the Occasion

A new biography lays bare the man and the moment.

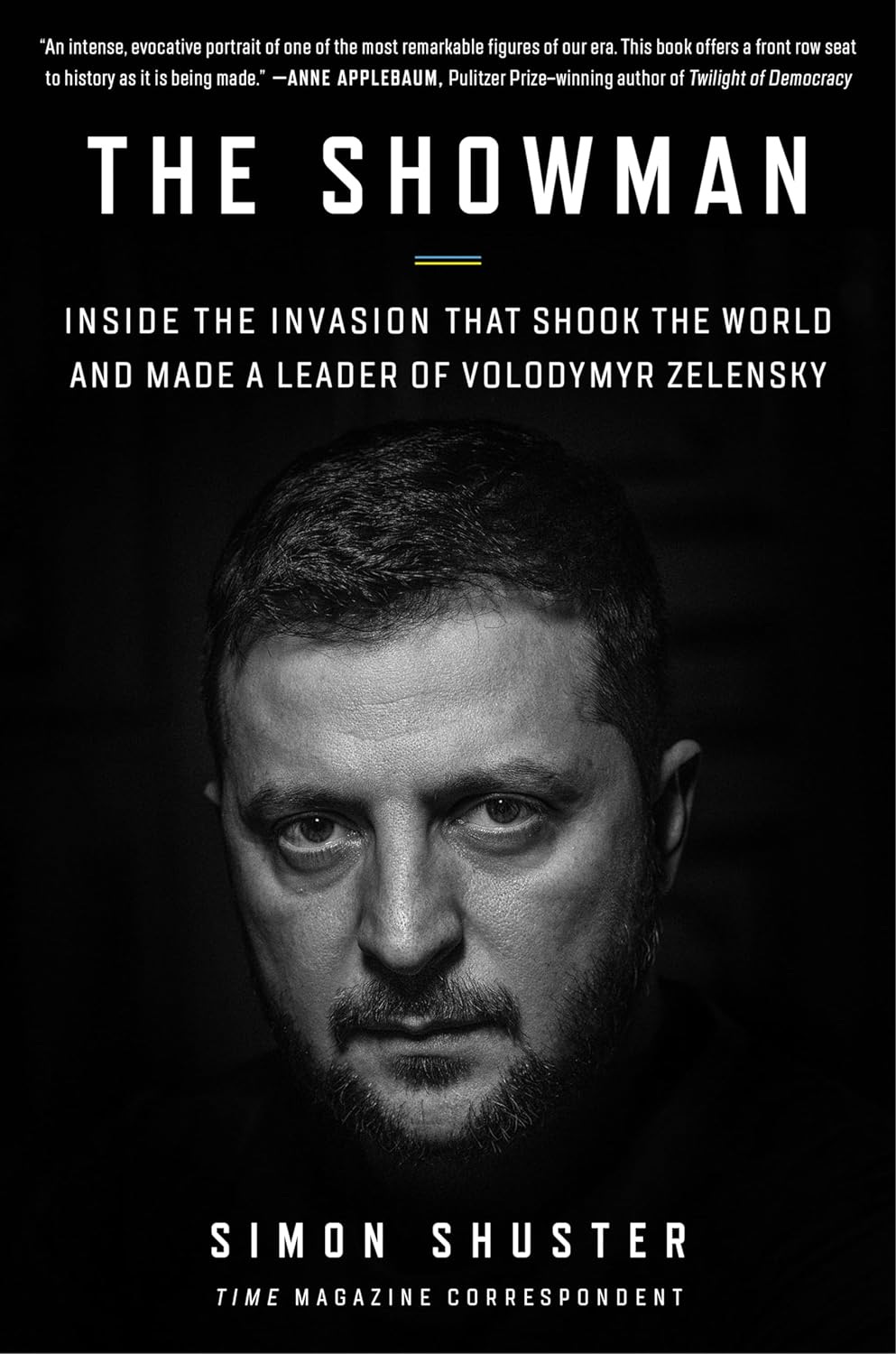

The Showman

Inside the Invasion That Shook the World and

Made a Leader of Volodymyr Zelensky

by Simon Shuster

William Morrow, 363 pp., $32.99

VOLODYMYR ZELENSKY IS NOT A GOOD MAN, but he may be a great leader. That is the main takeaway from The Showman, Simon Shuster’s new biography of the Ukrainian president. As the Russia-Ukraine war has become politicized in the United States, both those for and those against U.S. support for Ukraine have sought to make Zelensky into a two-dimensional figure—either a hero of democracy or a symbol of Western decadence. Shuster’s biography restores depth to the man the world has tried to flatten.

Shuster, who spent years reporting on Ukraine for Time magazine before Zelensky even entered politics, gained impressive behind-the-scenes access to Zelensky and his circle, glimpsing the life and personality of the man who dominates Ukrainian politics (for now) and who has become a global icon. Shuster’s insight into the country’s culture and political landscape informs his reporting on Zelensky’s rise, early presidency, and wartime leadership.

Zelensky’s life story lends itself well to biography. Born in an impoverished nation to parents who wanted him to go into a “real” career, Zelensky rebelled, becoming a comedian and comic actor, and eventually one of the most famous, and wealthy, celebrities in Eastern Europe. To appease his parents, he also completed a law degree while with his comedy troupe in Moscow trying to make it big on Russian TV in the late 1990s. Shuster describes a revealing video of Zelensky when his team tied for first place in a comedy competition, which the young comedian clearly thought would have been a victory if not for an unfair intercession by the showrunners. “Though he catalogued such gripes with an endearing smile, Zelensky was clearly unwilling to share the crown with anyone. He needed to win. Years later, when he recalled these competitions from his childhood, Zelensky admitted that, for him, ‘Losing is worse than death.’”

Zelensky learned other lessons in that period, too: He and his troupe were subjected to the typical derision with which Muscovites treated provincials—especially from the former imperial possessions. “Like slaves,” Zelenkys’ wife, Olena, put it. According to one account, a casually antisemitic remark was the reason the group decided to leave Moscow in 2003. He and his group could parody Putin as he rose to the presidency and consolidated power—and they did—but they could never be in in Russia.

The Zelensky whom Shuster describes has, like other actor-politicians, a default character that serves him equally well in theater and politics (after all, how much of a difference is there between those two pursuits?). “Standing around five and a half feet tall, with glinting eyes that bulged a little beneath his dark, expressive eyebrows,” the ability “to seem relatable, normal, like one of the guys” was the foundation of his career. His most famous character, Vasily Goloborodko, the high school history teacher who gets elected president on an anticorruption, good-government platform in the hit TV series Servant of the People (also the name of Zelensky’s party), is nerdy, a little schlubby, gets tongue-tied, and has a complicated family life, but hides a cleverness and political savvy that only reveals itself over the course of several seasons. Though Zelensky is “his generation’s greatest satirist, one whose wit had a way of winning any audience by nailing politicians to the wall,” the cutting parody of Servant of the People hardly ever comes from Goloborodko’s mouth.

Riding his fame and a wave of anticorruption sentiment left unfulfilled from the 2013–14 Revolution of Dignity that ousted President Viktor Yanukovych, Zelensky became president in 2019, repeating in life the seemingly impossible rise to power of a humble, honest, workaday guy in his early forties that he had depicted in art just a few years prior.

It should come as no surprise that, like Goloborodko, the real Zelensky was a far different person from the character he put on during his campaign.

The portrait Shuster paints is less likable, more formidable, and more human: a thin-skinned, egotistical neophyte who ran for the presidency without any serious aims and without even informing Olena. After months spent begging him not to run because of how little time he spent with his children, Shuster recounts, she only learned of his announcement after friends reached out to ask about it. When she asked why she had to be the last to know, he reportedly responded, smiling, “Oh, I forgot to tell you.”

Zelensky is still married, but the character of Goloborodko is divorced and has a somewhat estranged and distant relationship with his son. In many ways, he feels closer to the unknown, unnamed people of the country than to his own family.

SHUSTER DEPICTS ZELENSKY as naïve on the campaign trail, inexperienced in office, and unprepared for war in ways that cost his country dearly when Russian forces crossed the border. In the winter of 2021–22, the Ukrainian Armed Forces’ Chief of Staff Valery Zaluzhny called for “a full-scale mobilization of reserves and the fortification of Ukraine’s borders with Russia to prepare for the coming attack. The president held him back, afraid that such measures would spread panic among the population and give the Russians an excuse to strike.” This was around the same time that the Biden administration was warning that a Russian invasion was “imminent”—and releasing evidence to support that conclusion—and Zelensky was urging Ukrainians not to worry. By that time, his anticorruption agenda had stalled after some early successes, he had failed to achieve peace with Russia in the Donbas, and his approval ratings were piteously low.

Thus it was unexpected, even to many close to him, that Zelensky rose to the occasion as the bombs started falling. He refused to abandon Kyiv, insisting he would stay in the capital and fight. He let the military leaders act without his uninformed interference, and immediately started to round up support from other nations. His leadership was Churchillian in the good ways—and also the bad: sometimes moody, obsessed with his own image, ignorant or prone to misjudgment on military matters, but brave, clear in communication, and able to understand, serve, and lead the spirits of his people as perhaps no one else could.

“In public his friends and staffers said Zelensky always had the qualities to do it well,” Shuster writes. “Privately they would admit to feeling shocked by his new self. Most Ukrainians did not believe he had it in him. Neither did I.”

The Showman does not tell the story of a man growing in virtue; rather it is a tale of a moment meeting the man. The qualities that made Zelensky a poor family man lend themselves well to wartime leadership. A workaholic walking symbol makes a better organizer of international support for his country than a father, after all. Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine was the product of several underestimations: He thought the Ukrainian military wouldn’t put up a significant fight. He thought Ukrainian society would roll over and accept domination. And he thought the comedian who mocked him on television all those years ago would run away.

Zelensky’s story, as Shuster tells it, is both disconcerting and reassuring. As so many biographers have done not only to Churchill, but also to Teddy Roosevelt, Franklin Roosevelt, Ronald Reagan, and so many other celebrated statesmen, Shuster exposes the flaws of his subject, bares his weaknesses and failings, and finds darkness where others saw only light. Yet Zelensky’s humanity—his mistakes, his failures, his imperfection—reminds us that great things are less likely to come from shining, perfect heroes than flawed human beings.

THROUGH NO FAULT OF SHUSTER’S, The Showman is inherently incomplete. The story he aims to tell is not yet done. As we approach the second anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the war isn’t close to over. And Zelensky’s life appears—notwithstanding the efforts of the Russians—not close to being finished, either. It is a testament to Zelensky’s leadership that Ukraine has lasted this long.

Since gaining independence in 1991, Ukraine has only re-elected a president once. At the moment, elections have been paused while the war rages. But it wouldn’t be surprising if, like Churchill, a grateful nation kicked Zelensky to the curb once the fighting is over—“after victory,” as Zelensky says. What does a man for whom “Losing is worse than death” do once he’s won and lost his job?

Churchill is (inexactly) quoted as having said, “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it.” Maybe Zelensky will take a hint from Goloborodko and decide to teach it.