Is the Argentina Bailout a Glimpse Into the Future of the United States?

Trumpism could dominate American politics long after Trump himself is gone—just as Perónism continues to dominate politics in Argentina.

AFTER DONALD TRUMP’S $40 BILLION BAILOUT of Argentina, the United States is now tied to the economic fortunes of a country that was once the wealthiest in the world but now ranks just below Kazakhstan. The American taxpayer will be on the hook for a government that has defaulted on its sovereign debt nine times, three of those in the last twenty-five years.

But let’s set aside for now the question of whether the bailout is a good idea or a bad one. What strikes me about the Argentina story is how much that country’s history holds up an uncomfortable mirror to our own history of the last few years.

I don’t just mean Javier Milei, Argentina’s president since 2023, who is so Trump-like that Trump is apparently willing to stake his political fortunes on rescuing him. Rather, the parallels go back to Juan and Eva Perón, and the Perónism that Trumpism is slowly beginning to resemble.

Juan Perón was elected Argentina’s president in 1946; his charismatic, if sometimes cartoonish, populism has towered over Argentine politics ever since. With his wife Eva—probably most familiar to Americans as the subject of the musical Evita—Perón crashed onto Argentina’s political scene in a moment of post-war upheaval. The country’s once-dizzying economic explosion was floundering. The Peróns’ populist appeals tapped into deep discontent among Argentina’s working classes toward urban and cosmopolitan elites in Buenos Aires.

The Peróns harnessed legitimate grievances about a deeply inegalitarian society segregated by class and geography. A former military officer, Perón fused populism with economic nationalism and bellicose rhetoric. Together, husband and wife were masters of propaganda and new communications tools—especially radio—using them to bypass mediating political powers and speak directly to voters.

Once in office, Perón governed with a heavy-handed and personalist style. Corruption ran rampant. He and his successors built a sprawling network of patronage and clientelism. He preferred to manage Argentina’s economy directly with tariffs, personal deals, and manipulation of monetary policy. Instead of a clear ideological vision, his populist protectionism was mostly instinctive and reactive.

The effects were disastrous.

As Scott Lincicome recently wrote in the Atlantic:

Central to Perón’s economic vision was an “import substitution industrialization” strategy, or ISI, that used tariffs, quotas, subsidies, localization mandates, and similar policies to push Argentines to produce domestically what they’d previously imported more cheaply from abroad. The approach was intended to fuel domestic growth, but it instead created insular and uncompetitive manufacturing industries saddled with high production costs, bloated finances, and rampant cronyism. Perversely, it also crushed Argentina’s globally competitive agricultural sector by diverting resources away from it and toward protected industries.

For American soybean farmers whose product is being squeezed on both sides by Trump’s tariffs and Argentina deal, that last bit might sound all too familiar.

MOST WORRYING OF ALL, though: Juan Perón died in 1974, but Perónism did not.

Instead, Argentina’s modern political history has been defined by an oscillating, perpetual conflict between those claiming to represent Perón’s legacy and those seeking to reject it. Through military coups, juntas, democratic restorations, elections, crises, collapsed governments, protests, and upheavals, Argentine politics has for decades been dominated by one question: Perónist or anti-Perónist?

The conflict has trapped what should be a wealthy, prosperous country in an unending loop of crisis, acrimony, and instability.

If you’ll forgive some simplification, here’s what happened: The combination of Perón’s populism and charisma, his corruption and mismanagement, and the country’s sizable social and class divides all contributed to extreme polarization. On one hand, Perónism’s emotional and populist appeal was irresistible; on the other, its governance failures were inescapable.

The bouncing between Perónist and anti-Perónist governments spurred a further cycle of economic crises—inflation in particular—and nearly each subsequent leader was swept into office by discontent with the prior one. Through it all, Perón and his legacy consumed and embodied all the other conflicts.

None of this is to say Argentine politics was static. To the contrary, both sides morphed dramatically: The Perónists shifted from interventionist economic policy to neoliberalism and then back again, while anti-Perónism has been, if anything, even more varied, ranging from outright rejection of democracy (again, multiple coups and a particularly brutal military dictatorship) to center-left liberalism to right-leaning technocracy.

Through it all, the divide has fallen along social, economic, and geographic lines. Perónism tended to represent working-class and lower-education voters in the rural areas and (especially) the sprawling industrial suburbs around Buenos Aires. While anti-Perónism speaks mostly to better-educated middle and upper classes in the capital and other cities.

POLITICS IN THE UNITED STATES, too, is sharply divided by social class and geography. Donald Trump consumes all the political oxygen—even when out of office—and the two-party polarization just keeps getting more acrimonious.

To be clear: I’m not predicting that the conflict between Trumpism and anti-Trumpism will continue to define our politics long after Trump leaves the scene. But it’s a possibility. And if Argentina’s experience is any lesson, it’s a future we should be working hard to avoid.

How do we do that? Two lessons for the opposition that seem to rise from the chaos of Argentina’s history.

Lesson one: Don’t let the political alternative be defined solely by opposition to Trump. Just as in Argentina, a blundering populist with an economically chaotic agenda is a ripe political target. But if that’s the only divide in politics, that line will eventually erode into a chasm. After enough time, nothing will be able to escape it.

Whatever it takes, find new fissures and fault-lines that can break and reshuffle politics in new ways, ideally across different divides than social class and geography. Look for new agendas and political conflicts that don’t map clearly onto Trumpism.

In other words: We need new things to argue about.

Lesson two, and this is especially true for capital-d Democrats: Don’t become the party of social elites and the status quo. Throughout its history, Perónism has always been able to call on a core populist argument: “If you’re unhappy with the way things are, we are the ones who will shake things up on your behalf.”

Anti-Perónism was always both too complacent in its elite roots and technocratic sensibilities to seriously challenge Perónism’s hold on the working class. As repeated crises undermined the middle class, this has become a persistent liability.

To avoid this fate, the Democratic party—our current anti-Trumpists—need to get more comfortable with populist and anti-establishment politics of their own. Similarly, those of us in the pro-democracy coalition whose sole priority is a rejection of Trumpism in all of its forms—I consider myself among this group—need to get more comfortable with what a more populist pro-democracy alternative would look like.

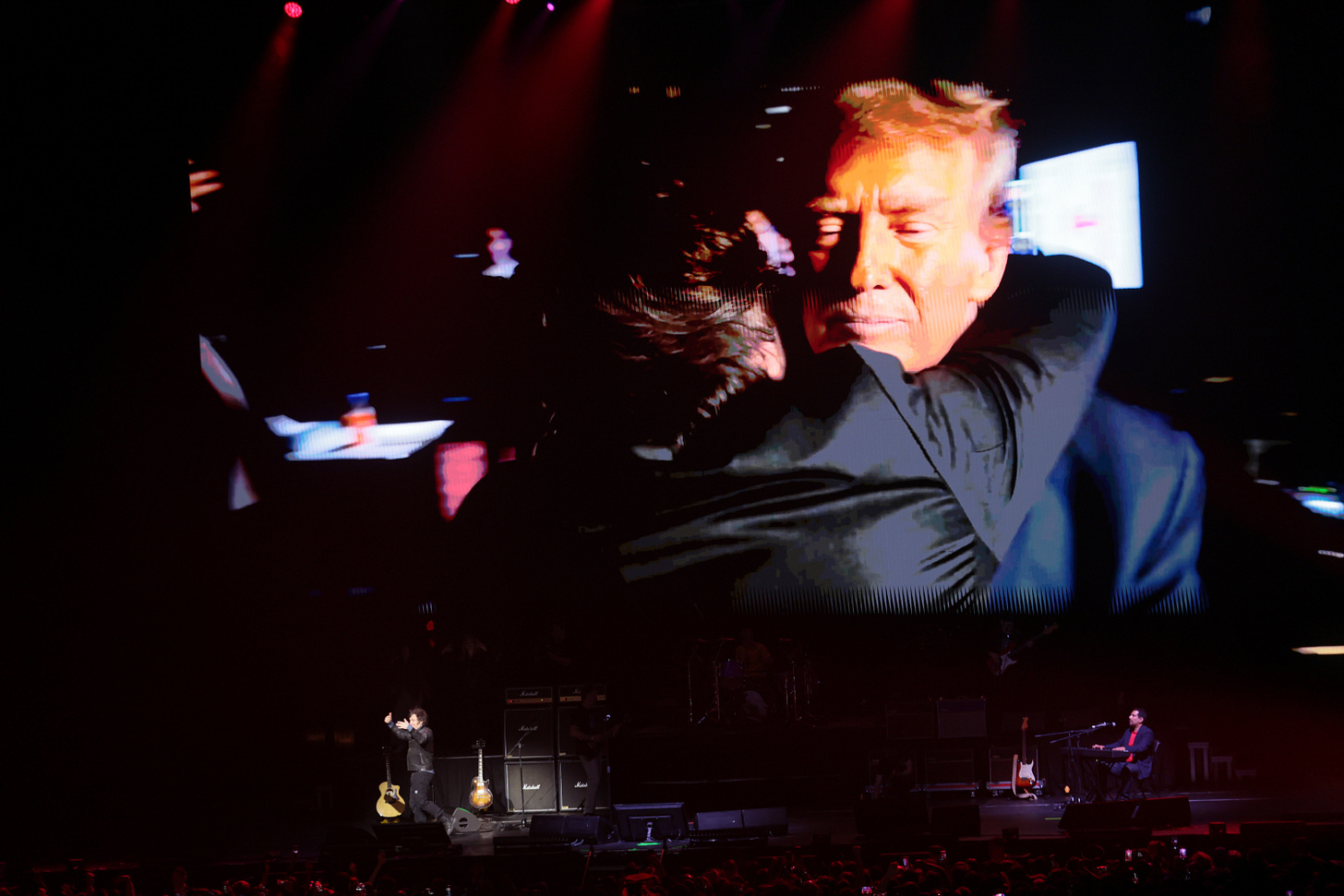

Ironically, the closest thing to a break from the cycle in Argentina was the election of Milei, who is both decidedly anti-Perónist and a would-be demagogue. Known as “the wig” for his distinctive hairstyle and sideburns and “the madman” for his outspoken eccentricities, Milei is an anarchist-libertarian with authoritarian tendencies and a fondness for cryptocurrencies, profanity, and Donald Trump. Maybe the sheer strangeness of Milei’s presidency will finally, after eight decades, reorient the country’s political divide into something new.

Or maybe it won’t. Milei too may be consumed by the divide and simply end up becoming the latest iteration of anti-Perónism before the Perónists eventually oscillate back into power. It’s too soon to tell. For now, Perónist parties remain his primary opposition in the upcoming elections.

Either way, it’s difficult to see how Argentina finds its way from here to greater political and economic stability. Even if it’s too late for Argentina, though, it’s not too late for the United States. We can and must find a way out of this trap—or eventually, we may be the ones begging for a bailout.