Is the “China Model” Finally Failing?

After decades of growing economic freedom, the Chinese people may also be demanding political freedom.

The past decade has not been kind to optimists who hoped that economic liberalization would beget a gradual embrace of democracy by countries around the world. “China will move increasingly to political freedom,” Milton Friedman predicted in 2003, “if it continues its successful movement to economic freedom.”

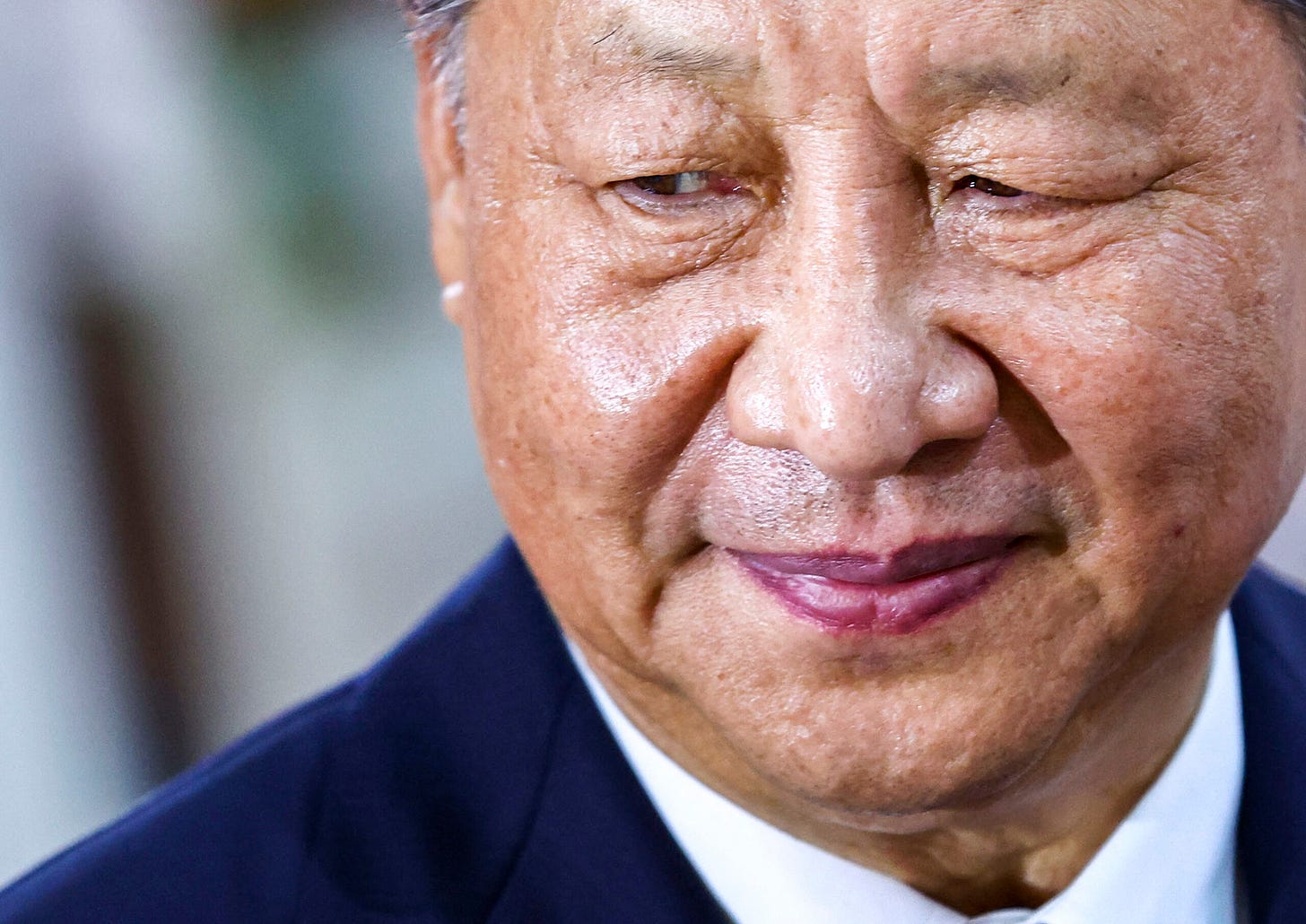

Of course, under Xi Jinping’s rule, China moved away both from its pro-market economic outlook and tightened the totalitarian control of its society with an Orwellian system of constant surveillance and concentration camps. Could the current protests against the government’s oppressive zero-COVID policies across Chinese cities vindicate Friedman and others who predicted a convergence of political and economic freedom?

Friedman’s claim was controversial, but it was not completely frivolous. The hypothesis traces its origins to Seymour Martin Lipset’s “modernization theory” of democratization, which argued that citizens of wealthier societies would demand greater political representation.

There are obvious counterexamples: democracies that have been operating successfully at a low level of economic development (India) or spectacularly wealthy societies that display no inkling to move to democracy (Singapore, Qatar).

Moreover, across autocracies, economic development provides rulers with resources to stabilize their holds on power—often by buying off or repressing opponents. Internationally, both Beijing and Moscow have used international economic linkages as levers to extract concessions from countries around the world, while avoiding excessive dependence on the West.

In fairness to Friedman, he emphasized that economic freedom was a necessary but not sufficient condition for political liberalization (whereas political freedom was neither sufficient nor necessary for economic liberalization). Clearly, political and social life is not a mechanical process. It involves “long and variable lags” (a term Friedman coined in reference to the effects of monetary policy), unpredictable cascade effects, and uncertainty.

Could it be that Friedman was essentially right, but his timing was off? The coming weeks may provide an answer to the question of whether a population that has had a taste of economic freedom can be bullied into ever more dystopian forms of totalitarianism, or whether the Chinese model unravels.

There is no question that adverse economic shocks, such as China’s economic slowdown amplified by its pandemic policies, threaten autocratic stability. In bad economic times, members of the ruling coalition suffer losses that may make them consider outside alternatives, while the broader population might get the sense, when faced with declining standards of living, that it stands nothing to lose from revolting.

Regime collapse, as the economist Timur Kuran observed about the fall of Soviet communism, is fundamentally unpredictable. Nobody knows what will trigger a cascade that will bring ordinary people into the streets and elites and the security apparatus to defect. Some autocrats, moreover, are far more effective at nipping discontent in the bud than others. And Xi has already more than proven his ruthlessness and brutality.

Furthermore, autocratic stability is not a matter of economic indicators alone. In the run-up to the Arab Spring, Middle Eastern and North African countries saw decent rates of economic growth, yet apparent economic progress was also accompanied by a deepening frustration with perceptions of the quality of life. Alexis de Tocqueville observed that revolutions often happen not when conditions deteriorate, but when they start to improve. Hope is a highly reactive political substance.

It would be foolish to try to predict where the current protests in China will lead. However, the regime faces vulnerabilities both in terms of subjective perceptions, which we’ve seen expressed on the streets of Chinese cities in recent days, and in terms of objective economic indicators. Following the country’s disastrous COVID response, most observers agree that the economy is unlikely to grow much faster than at 3 percent in 2022—well below the official target. Poor economic performance is likely one the factors behind China’s discontinuation of hundreds of economic statistics that were once publicly available.

Yet, regardless of whether more repression is enough to keep Xi in power, one thing ought to be clear: The apparent stability of autocratic regimes, from China to Russia to Iran, is an illusion—just like the rigor mortis–like stability of the final decades of the Soviet Union belied the system’s inexorable decay.

While forecasting autocratic breakdowns or gradual liberalization of dictatorial regimes is a fool’s errand, human yearning for freedom is real and irrepressible—especially once already tasted. If we are lucky, we may see its fruit in our lifetimes, in China and beyond.