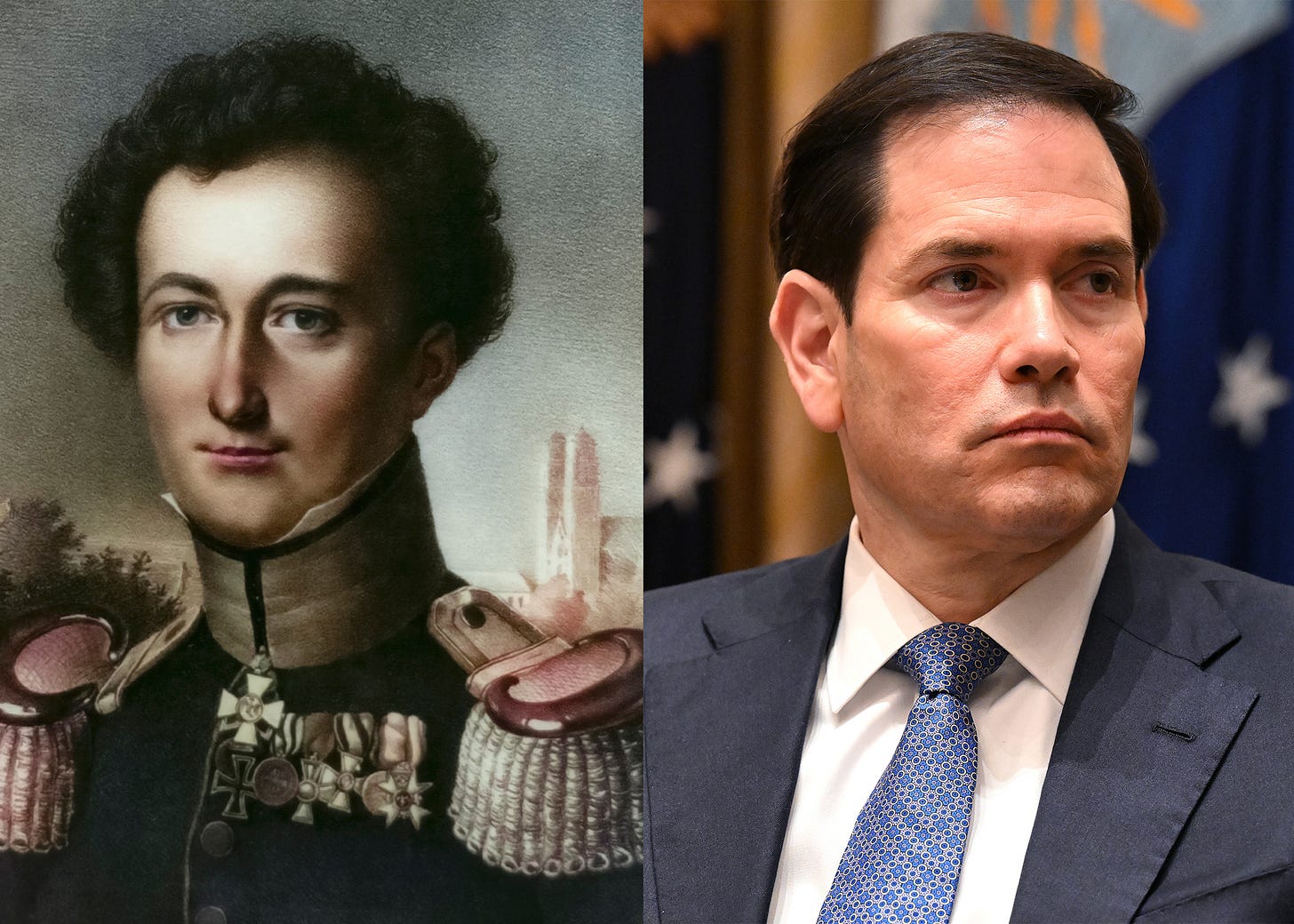

A Letter from Clausewitz to Secretary Rubio

Channeling the author of ‘On War’ on the U.S. pursuit of peace in Ukraine.

During my military career, I spent countless hours studying Carl von Clausewitz and other military theorists whose work still shapes how we think about war, strategy, and—just as importantly—how wars end. Their ideas remain relevant not because they offer formulas, but because they illuminate how human beings, governments, and armies act under pressure. Recently, I found myself asking: What would Clausewitz say about the quest for peace between Russia and Ukraine? Perhaps he might write a letter like the one below. –M.H.

My Dear Mr. Secretary (with copies furnished to Messrs. Witkoff and Kushner) –

Allow me, from a place beyond politics and beyond time, to offer some reflections as you undertake the difficult task of peacemaking. I have no objection to your pursuit of peace; indeed, I devoted much of my life to understanding its relationship to war. But I must caution you: Peace, like war, has an essence. It cannot be dictated by impatience, convenience, or diplomatic theatrics. It must be anchored in principles that endure after the cannon fall silent.

I have observed many leaders—kings, emperors, ministers—seek peace not because justice demanded it, but because they found war wearisome. Such efforts rarely end well. Given this, I ask you to consider not merely whether any plan you might conceive will produce a document signed on a dais by your president in your capital, but whether it will produce actual peace in Europe, and whether it protects the people whose lives and liberty hang in the balance.

You may recall that in On War I wrote of a trinity: the people, the army, and the government. A durable peace that flows from any war requires that the trinity of the aggrieved nation remain aligned and strong. In Ukraine’s case, the people long for peace in a way no distant diplomat can truly understand or match; the army has fought with cohesion and determination; the government, for all its internal pressures and even accusations of corruption, retains legitimacy because it defends its citizens’ survival. That unity is the very reason Ukraine has endured.

But peace is not simply the cessation of gunfire. It must also restore and protect the humanity that war has endangered. In considering any settlement, the diplomat must also ask: Does the peace plan contemplate the return of deported children? Does it free prisoners of war and innocent civilians? Does it secure the rights, property, faith, and future of millions living under occupation? Or does it treat these human dimensions as inconvenient footnotes? A peace that ignores the fate of people under tyranny is merely the preface to their continued suffering.

You may be tempted to believe that “ending the war” is synonymous with “creating peace.” It is not. A pause of months or even years, achieved by granting the aggressor new territories, relaxed sanctions, or the ability to rearm at leisure, is not peace but preparation for renewed assault. A true peace must reduce the likelihood that the aggressor will resume or expand its violence; it cannot strengthen his hand while weakening the victim’s.

In your present deliberations, as described in press accounts, I see echoes of past mistakes: asymmetrical restrictions placed on only the defending nation; the granting of fresh territory to an invader who failed to win it on the battlefield; the lifting of sanctions that would allow the aggressor to rebuild his armies; the absence of enforceable guarantees to protect the victim in the years ahead. This approach, which weakens the assaulted and strengthens the assailant, creates the conditions not for peace but for the next war—a war that will be bloodier because the world will have taught the aggressor that force, not law, prevails.

During my lifetime, international law was a loose garment worn only when convenient. Today you possess institutions intended to prevent the very type of conquest now unfolding. If any plan lacks consequences for aggression, if it grants impunity for war crimes, if it effectively amends your modern U.N. Charter by permitting territorial seizure through violence, then it undermines a global order that generations after me tried desperately to build. Such a precedent would not remain confined to Europe. Others will learn from it. Others will imitate it. You will have institutionalized the rule of force.

You will be told, no doubt, that the United States has offered guarantees before, and that those guarantees have failed to prevent catastrophe. And you must admit that this is true. Ukraine once surrendered an arsenal of immensely destructive weapons, the power of which I could not comprehend, in exchange for such assurances. A nation that has tasted betrayal remembers it vividly. Therefore, if you intend to promise protection, that promise must carry actual mechanisms, resources, and consequences. Vague assurances are not security; they are illusions, and illusions in great power politics are fatal.

Now, Mr. Secretary, a word about the nature of fighting power—something far too many of your modern strategists reduce to charts and numbers. I wrote long ago that the strength of an army is the product of its moral and physical forces. Some today summarize it as an equation: P=WxM, or power equals will multiplied by material. I would suggest that your modern warriors mistake this for mathematics when it is really a metaphor. The truth is that will magnifies limited resources, while its absence can nullify superior ones. This explains why large powers (both Russia and your own nation) have faltered in places like Afghanistan, and why smaller nations, when motivated by the justice of their cause, have outlasted supposedly superior enemies. It appears to me that Ukraine endures because its will is intact. Russia struggles because its trinity is fractured, its moral forces rotten at the core.

WHICH BRINGS ME to the autocrat commanding Russia’s war, who seems more like something from my era than from yours. During my days, the armies of Europe confronted Napoleon, a man whose ambition outran his judgment. Europe tried to reason with him, then to accommodate him, and finally learned the hard way that a man bent on domination must be constrained, not indulged. Twice he was removed to islands—Elba, then Saint Helena—so that the continent could recover. If a ruler wages war as though peace were merely the interval between invasions, he cannot be trusted with a future leading any nation. Any plan that rewards such a man with new lands or relieved sanctions is not a peace treaty but a capitulation.

You must therefore consider whether your vision of peace is one that will endure or one that merely grants the aggressor time to reload. Ask yourself: Does the proposal end the war, or does it create space for the aggressor to wage the next one? Does it protect the innocent, or does it consign them to continued subjugation? Does it reinforce the law of your nations, or does it hollow it out from within? And does it fortify the nation that was attacked, or does it weaken it when its survival depends on strength?

As I learned through a lifetime of war and the study of conflict, peace cannot be separated from justice, nor from the balance of forces that shape the political order. If you craft a peace that honors human dignity, protects sovereignty, holds aggressors accountable, and strengthens the will of those who defend their liberty, then history will remember you as a statesman. If you craft a peace that rewards conquest, ignores the suffering of innocents, and burdens the victim while absolving the aggressor, then history will remember you as something else entirely.

Seek the former, Mr. Secretary. The world has enough examples of the latter.

Respectfully,

Carl von Clausewitz