The Memories That Make a People

Library of Congress exhibition shows the power of “the real thing” to shape citizens.

Collecting Memories: Treasures from the Library of Congress

Library of Congress Jefferson Building, Washington, D.C.

through December 2025

BILLIONAIRE PHILANTHROPIST DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN’S largesse has benefited major arts centers and sites of civic importance around the United States—especially in Washington, D.C. and New York City, such as Lincoln Center, the Kennedy Center, the National Archives, the U.S. Holocaust Museum, and the National Gallery of Art. He has helped fund the restoration of the Washington Monument, the Jefferson Memorial, and the Lincoln Memorial. A meeting room at Mount Vernon is named after him; so is the visitor’s center at Monticello. You can see his name at the tail end of PBS programs several times each year.

Rubenstein’s passion for supporting projects and institutions that illuminate American history, art, and culture—what he calls “patriotic philanthropy”—is aimed at “remind[ing] people of the history and heritage of the country,” both the good and the bad. He hopes that will result in better citizens and a stronger democracy.

Among the latest recipients of Rubenstein’s patriotic philanthropy is the Library of Congress, which he recently gave $10 million to create a new gallery devoted to treasures from the Library’s collections. The inaugural exhibition explores how cultures preserve memories, and the role the Library plays in collecting and preserving memories for Americans. The Rubenstein Gallery is in the Library’s Thomas Jefferson Building, a prime example of the exuberant Beaux-Arts architecture popular in the Gilded Age—ornate, theatrical, and grand in style.

The exhibition is part of a multiyear plan to make the Library of Congress a more attractive destination for visitors by creating new galleries, displays, and interactive spaces. Scholars are familiar with the Library’s extensive research holdings and often burrow for hours or days in its many spectacular reading rooms, but the Library is not as well known to the public as the Smithsonian and the other attractions of the nation’s capital. As Rubenstein explains, “You usually don’t go to the Library of Congress because you don’t know that the Library of Congress is more than just a library.” Exhibiting treasures from the Library’s collections is meant to entice and dazzle a wider range of the public—to rope in school groups and tourists who will discover magic in these historic treasures.

“The stories told by these items still inspire and amaze,” promises Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden. So what, from the Library’s unfathomably vast collection of 178 million items, is on display?

The roughly 120 items in the initial six-month rotation of the exhibition include moving images, voice recordings, diaries, manuscripts, photographs, maps, and prints. State-of-the-art lighting and exhibit cases have been designed to ensure artifact safety, and audio stations allow visitors to hear oral histories collected from such Library divisions as the American Folklife Center.

The range and diversity of the Library’s holdings ensures a lively and eclectic exhibition experience. As soon as you walk into the gallery, you’re surrounded by exhibit walls that flash with constantly changing images from various collections—one moment it might be Charlie Chaplin cavorting, the next it’s the Radio City Rockettes performing their famous high kick. The main section of the exhibition features double rows of glass cases displaying artifacts, some standalones, others organized in pairs or groups. The Library’s director of exhibits, David Mandel, describes the intention of such placements as seeking “synergies between the stories” embedded in the artifacts.

A standout item: a “track map” based on Meriwether Lewis and William Clark’s expedition to explore the western territory of the United States acquired in the 1803 Louisiana Purchase. Published in 1814, this was the first printed map to display the trans-Mississippi West, which was then an unknown expanse of potential American settlement.

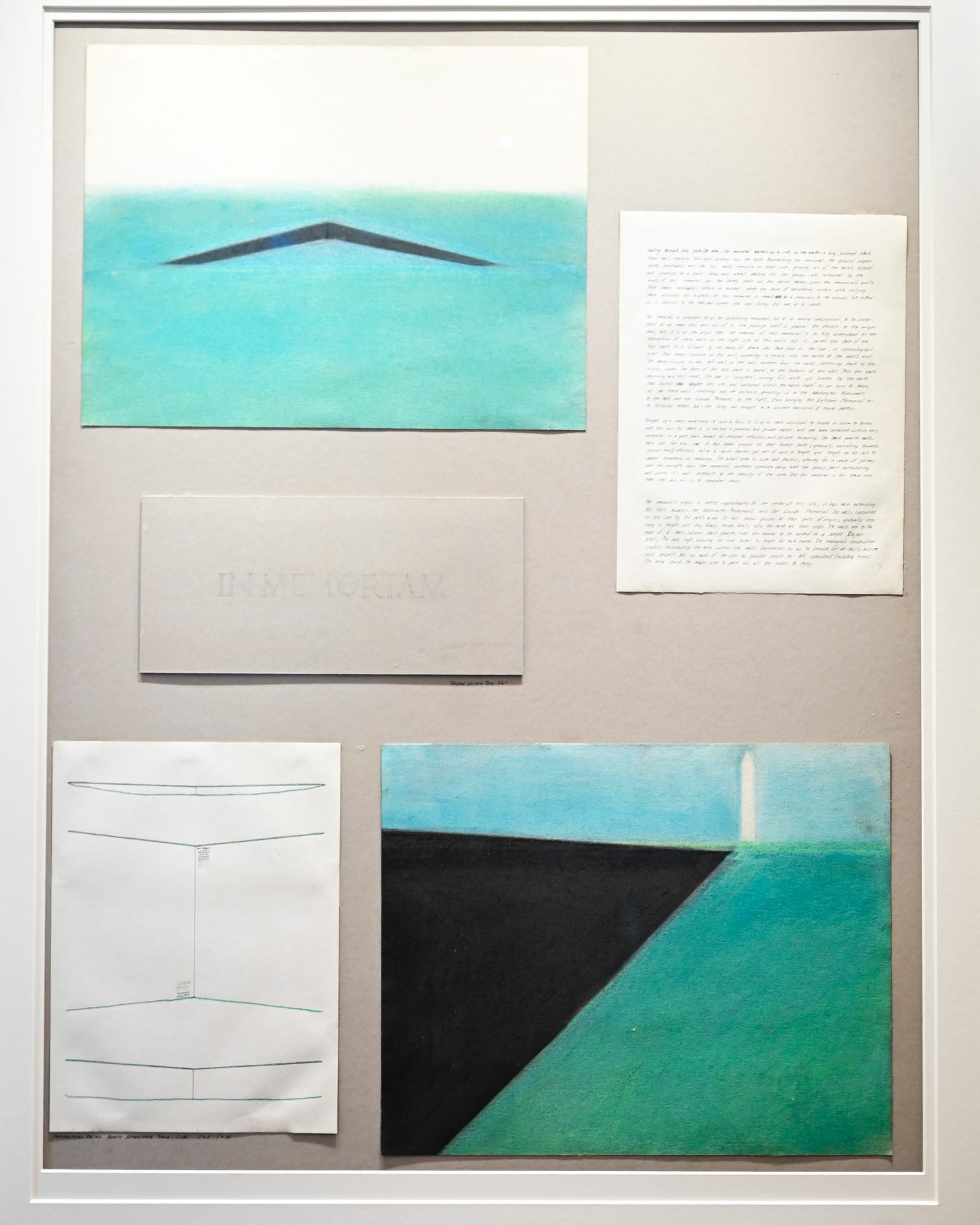

A particularly smart curatorial juxtaposition puts Robert Mills’s design sketchbook for the Washington Monument, dating from 1835 to 1840, next to Maya Lin’s 1981 entry drawings for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial design competition—a vivid illustration of how architects generations apart and planning very different projects of commemoration still must think through some of the same kinds of questions.

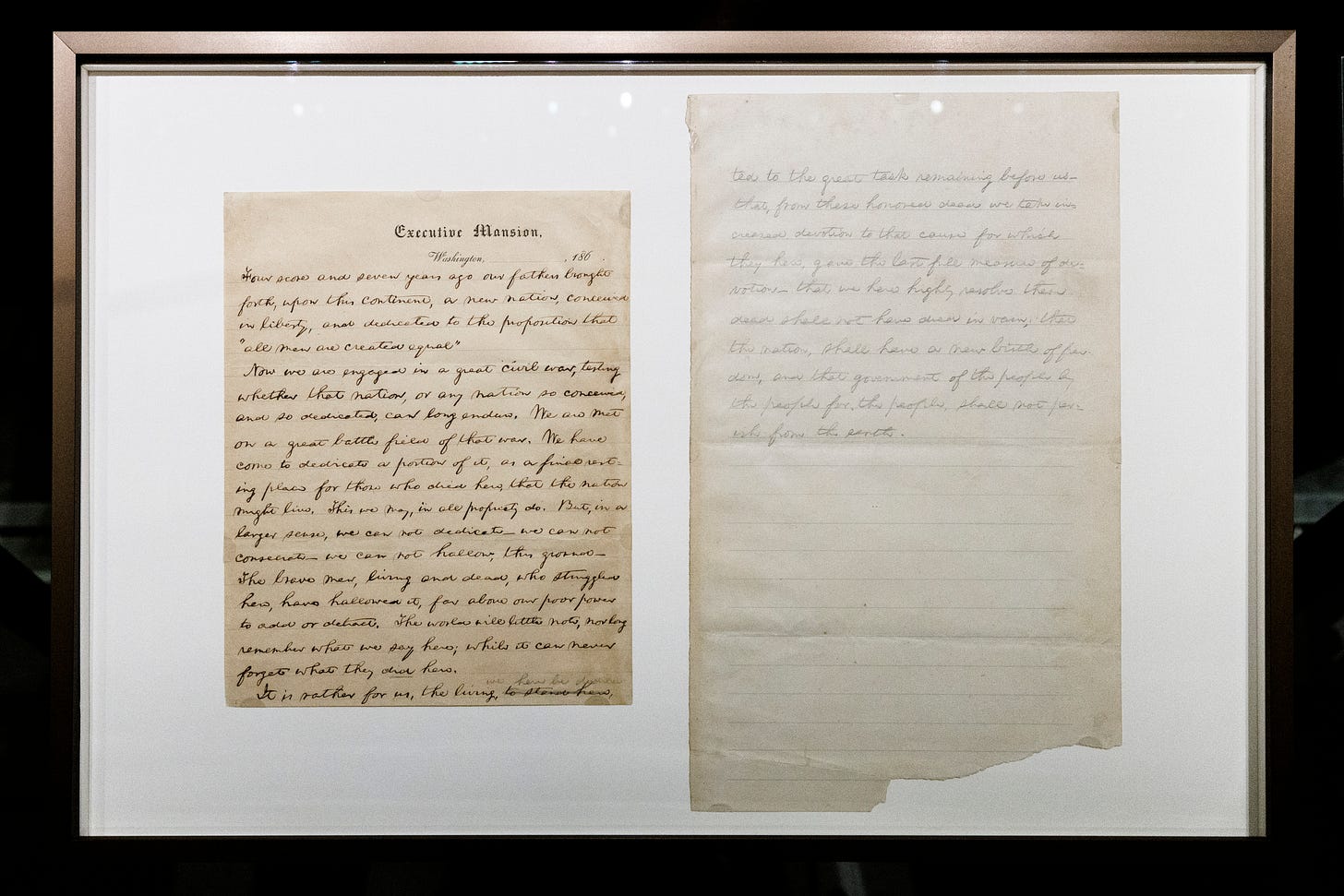

For me, and I’d wager for most visitors, the most jaw-dropping item in the exhibition is a manuscript of the Gettysburg Address. There is a myth that President Abraham Lincoln scribbled this landmark speech while riding the train from Washington to Gettysburg in November 1863; the reality is that he began writing it when he was first invited three months earlier. He went through several drafts—the one on display is known as the “Nicolay Copy” because the president handed it to his private secretary, John George Nicolay, after he finished delivering its 271 words. The first page is written on Executive Mansion (now the White House) stationery in ink, while the second page is written on a different kind of paper in pencil. Scholars believe Lincoln rewrote the ending of his talk while he was actually at Gettysburg, including the immortal final line “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Also on display are the contents of Lincoln’s pockets on the night of his assassination. The assortment includes his silk-lined leather wallet, an ivory-and-silver penknife, and a mended pair of eyeglasses. These items went to his son Robert Todd Lincoln and were donated to the Library by a granddaughter in 1937.

THE COLLECTING MEMORIES EXHIBITION underscores the power and the sheer joy of seeing “the real thing.” When I curated exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, I always sought “real things”—their inherent authenticity captivated visitors. For an exhibition on broadcast pioneers, I featured the microphone Edward R. Murrow used to broadcast from London during World War II. During the Blitz, he took the microphone into the BBC’s Broadcasting House subbasement to send the sounds of war to Americans, beginning each broadcast with his signature “This . . . is London,” and ending with “Good night, and good luck.” For an exhibition on American musicals, I showed one of the four extant pairs of the ruby slippers Judy Garland wore in The Wizard of Oz. The display case had to be cleaned regularly because people were so entranced that they kept kissing it!

The history of musical theater is represented in the Library exhibition via a fascinating artifact: Oscar Hammerstein’s lyric worksheet for “Do-Re-Mi” from The Sound of Music. On the yellow legal pad, the song—Maria’s way of teaching the von Trapp children the rudiments of music—is still a work in progress as Hammerstein experimented with lyrics. He originally tried to find a rhyme for “Sow is what farmers do with wheat.” His breakthrough moment came when he switched to “Sew—a needle pulling thread,” and followed that with “Tea—a drink with jam and bread.” Voila!

Another musical item made me smile: Resting on an exquisite platform is President James Madison’s crystal flute—a rare instrument made of real crystal.

Before the White House was burned in 1814 by British troops, Dolley Madison rushed around grabbing important personal and historic items to rescue, including the crystal flute. Two years ago, Hayden invited musician and rapper Lizzo to play the instrument, which she did both in the halls of the Library and onstage at the Capital One Arena. It was a magical moment as the craftsmanship of one era and the preservation work of two centuries of caretakers were met with the creativity of a contemporary artist.

And that’s what this exhibition does so well. These unique treasures from the Library’s collection, these “real things” we can see up close for ourselves, are not just reminders of where we came from but sources of inspiration for the kinds of people we want to be now: custodians of a shared yesterday, citizens responsible for today, and creators dreaming of a new tomorrow.