My Life Shows the Horror of RFK Jr.’s New Vaccine Guidelines

The Trump administration just yanked the recommendation for a vaccine that can spare people from what I went through.

I KNOW THE SUFFERING THAT RFK JR.’S VACCINE CHANGES will cause, because I’ve lived it.

In May 2004, I slowly woke up from a drug-induced coma to find myself in an intensive care unit at what was then called the University of Kansas Hospital. There was a feeding tube snaking down one of my nostrils, there were IV’s in both my arms, and a catheter was running from the lower part of my body. The breathing tube that had painfully gagged me during fleeting moments of half-consciousness was mercifully gone. But I couldn’t move my hands and feet, which was disturbing. They were covered in bandages so I just assumed the hospital staff had wrapped the bandages way too tight. Not so.

A doctor came and told me I had contracted meningococcal disease, a form of bacterial meningitis that transformed me overnight from a perfectly healthy 22-year-old college student, working at the school newspaper and playing just about every intramural sport, to a comatose ICU patient, fighting for my life on a ventilator. The infection, which I may have gotten just from sharing a drink with someone, had ravaged my bloodstream. Heavy doses of antibiotics eventually killed the bacteria and after three weeks the hospital staff had been able to stabilize my internal organs. But the blood flow to my extremities had not fully returned, and never would.

“You have tissue damage equal to third-degree burns over 30 percent of your body,” the doctor said.

When the staff removed the bandages I saw what that meant: My arms and legs had turned pitch black, and my fingers and toes were dried up, lifeless claws. My limbs were rotting while still attached to me. My initial response to this was just straight-up denial. I couldn’t process what I was seeing or deal with it emotionally, so at first I just didn’t even try. Those weren’t my arms and legs. And even if they were, they were going to come back and be fine, no matter what those doctors said.

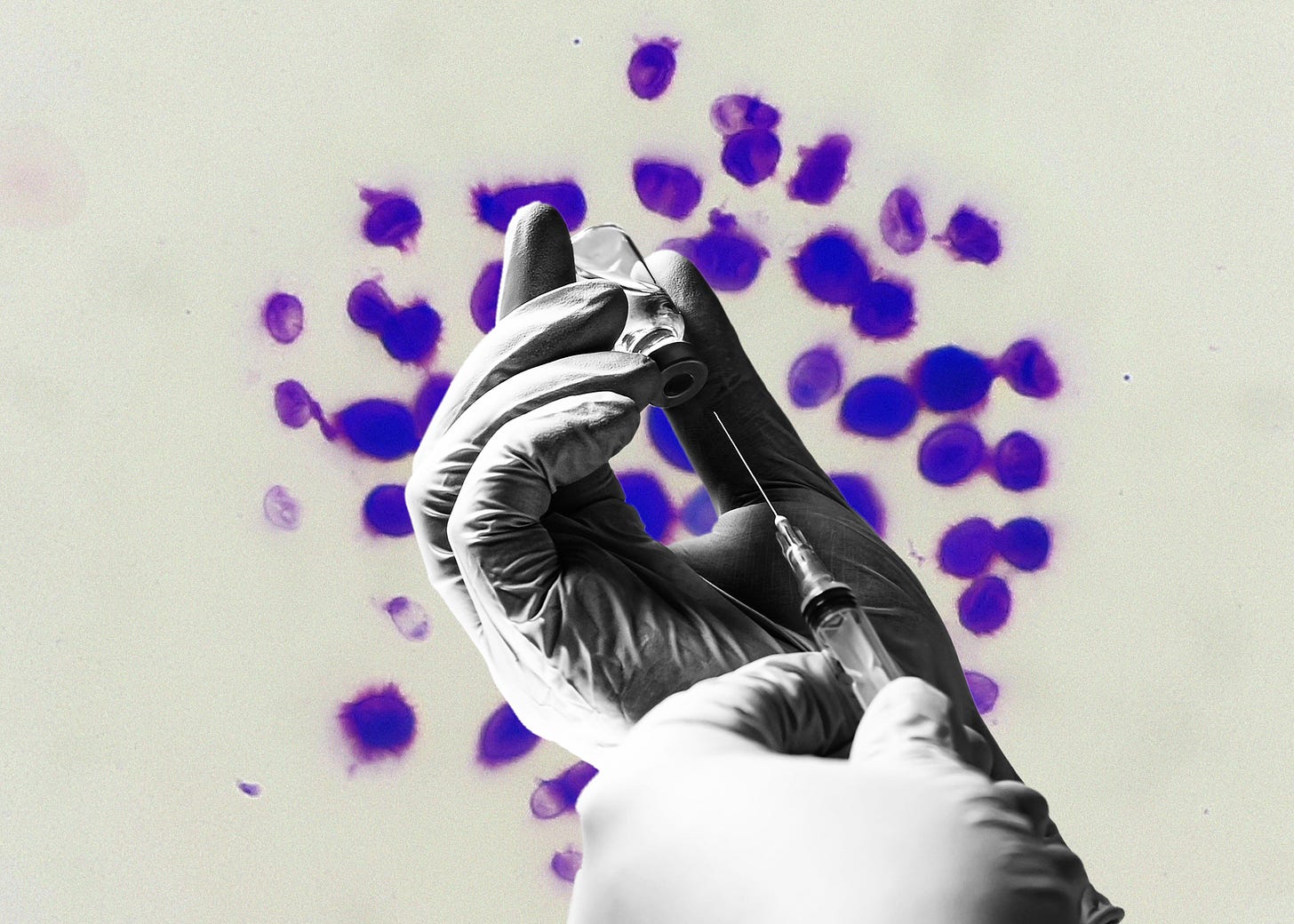

But during the following three months in the hospital’s burn and wound unit, things became too real to deny. First there was “debridement,” a process wherein doctors, nurses, and wound techs sliced off layer after layer of dead tissue, searching for something that would bleed, in an effort to save as much of my limbs as possible. I was awake for that, and had nightmares about it for years afterwards. Then multiple skin-grafting procedures, in which a plastic surgeon took the top layer of skin from my thighs and stapled it over debrided areas that were so big they wouldn’t scar over on their own. Then surgeries to amputate my fingers and toes because hospital staff had debrided down to the bones and tendons and nothing was left alive; only my right thumb was spared. [Editor’s note: Some photos of what’s described here—graphic patient images—appear below.]

During that time, denial gave way to the other stages of grief.

Anger: “Why did this happen to me? I don’t deserve this.”

Bargaining: “God, if you give me back one of my hands, just one, then I’ll spend the rest of my life feeding poor kids in Africa.”

Depression: Laying in bed, bawling my eyes out, thinking, “How can I go on?”

Acceptance: “My old life isn’t coming back, as much as I want it to. I have to figure out how to make something of this new life.”

But I was one of the lucky ones. Meningococcal disease kills 10 to 15 percent of people who get it—often within twenty-four hours of their first symptoms. Another 20 percent suffer permanent damage, including amputations like mine, but also brain damage, hearing loss, or vision loss. Multiple doctors have told me it’s one of the illnesses they fear most.

But vaccines help. After a broad-based vaccine that prevents meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, and Y was added to the CDC schedule in 2005, the number of cases each year declined precipitously, going from thousands to hundreds.

So it’s baffling that Donald Trump, RFK Jr., and their hand-picked vaccine advisers recently decided it’s no longer necessary to protect children from this highly preventable disease and sidestepped the usual process to take it, and other vaccines, off the CDC schedule.

For someone like me who has spent the last twenty years trying to explain the dangers of meningitis and convince people to protect themselves through vaccination, their decision to unilaterally remove the meningitis shot from the CDC’s recommended schedule was mind-boggling, dispiriting, and infuriating. It also may be against the law. As a writer with the Association of Health Care Journalists put it this week, the Trump administration “has not provided a scientifically or legally sound explanation for the change.”

Meningitis is a rare disease, but for the last few years rates have been rising, and no one really knows why. Now is not the time to discourage vaccination.

KNOWING HOW HELPFUL A VACCINE CAN BE, I have spent twenty years testifying in state legislatures to add meningitis to the list of shots required for school attendance. When a new vaccine was approved in 2015 for serogroup B meningitis, I testified before the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) with a group of other advocates to try and get the CDC to recommend it for all adolescents as well. They declined, citing a lack of long-term data. This is how I knew that statements RFK Jr. and FDA commissioner Marty Makary made last year about previous versions of ACIP and CDC being “rubber stamps” for vaccines were false—I was there in 2015 and they didn’t give me the stamp I was looking for.

The meningitis vaccine will still be available based on “shared clinical decision-making,” but the general public doesn’t really know what that means. It causes confusion for parents already exhausted from having to make a thousand decisions a day, and results in lower vaccination rates.

We’ve already seen proof of that with meningitis vaccines. About 90 percent of American adolescents currently get at least one dose of the MenACWY vaccine—the one RFK Jr. and company just removed from the CDC schedule. The MenB vaccine prevents the exact same disease, but because it’s not on the universally recommended schedule, only about 37 percent of adolescents get it.

I’m hopeful that uptake of the MenACWY shot won’t drop that low. Thankfully, it will remain on most states’ required lists, at least for a while, and a majority of Americans understand that the current administration has no credibility when it comes to vaccines.

It’s also encouraging to see some prominent Republicans already pushing back on the changes, including Sen. Bill Cassidy, a physician from Louisiana, whose vote helped get RFK Jr. confirmed as HHS secretary. Cassidy rightly stated that the new vaccine guidelines are not based on scientific evidence and would make America sicker.

But there has been a concerning lack of leadership from others who should know better, including a glowing statement about the changes from Sen. Roger Marshall, a physician and a Republican from Kansas, the state where I lived when meningitis nearly killed me.

When vaccines got sucked into the vortex of COVID-19 partisan polarization it caused Republicans to become more likely to die of COVID than Democrats. I fear the same will happen with meningitis—that kids will die or become disabled for no reason except for the political party their parents identify with. That’s appalling.

I continue to struggle with the effects of meningococcal disease to this day. I recently had my leg amputated below the knee because the toeless stump of my right foot had deteriorated in the last few years, causing chronic pain that made it hard to walk.

Now is the time for serious, organized opposition to these drastic vaccine changes. Anti-vaccine activists will inevitably try to align state laws with these new CDC guidelines. That’s unthinkable. No one should have to go through an experience like mine—not when there is a safe, simple shot that can prevent it. I hope our country can step back from this madness before too much irreversible damage is done.

Andy Marso was a member of the guideline development group for the World Health Organization’s Defeating Meningitis by 2030 roadmap. He is a former health reporter for the Kansas City Star and author of a memoir about his experience with meningitis who now lives in Minnesota and edits a career and practice journal published by a national physician organization. He is writing in his personal capacity.