National Opinion Polls Don’t Matter. Swing State Opinion Polls Do.

Nationwide samples don’t tell us anything about who’s likely to be president in 2025.

LAST WEEK, AS I WAS STROLLING through Cleveland, along the banks of Lake Erie, and through a farmers’ market near the Cleveland Clinic’s main hospital, I took the opportunity to quiz some people I ran into about how they think the presidential race is going. The physical atmosphere was clear; the political atmosphere was much murkier. The general consensus was that it was “too close to call,” going down to the wire, dependent on what “wokeness” means. “The polls I am looking at say Biden is up by about one point, and that means Trump has a good chance of beating Biden,” one interlocutor told me.

Fine. The national polls do say that. But I followed up by asking them if they knew where the two potential candidates stood in state polls, which might be a better predictor for who will win the Electoral College—that is, who will serve the next term as president.

I was surprised by the reactions of the dozen or so individuals I asked. All of them said they were unaware of any state polling measuring Biden against Trump (or anyone else) based on their preferred news sources, and a majority said national polls were a much better predictor of how things would turn out anyway.

When I told them one recent aggregation of state polling had Biden up by 302 to 234 in the Electoral College—about the same margin by which he beat Trump in 2020—they were surprised. Some even dismissed the figures as outliers that didn’t accurately represent the “very close” race.

Further efforts to explain the difference between the national popular vote and the Electoral College vote were unsuccessful. I point this out not as some advocate of changing the Electoral College system, nor to suggest that the public is stupid. But I did find it surprising that, even though two presidents in the past 25 years have been elected despite losing the popular vote, and even through Trump came within a few thousand votes in the right states for doing so again, the importance of the Electoral College hasn’t fully penetrated the political consciousness of my impromptu research subjects.

It seems that people may have had more of an appreciation for the Electoral College in the past. A complex alignment of trends has changed that. The media know that national polls get more eyeballs than those from Michigan or Pennsylvania. Trump campaigns almost exclusively on national issues or personal grievances and rarely on state or regional issues. Social media, which by its nature prioritizes larger communities over smaller ones, pushes individuals away from state issues that past presidents used to build their winning coalitions.

“What has happened is that pockets of people in different states—who favored one local or state issue over another in importance—used to have more power in the presidential race,” says Ohio Northern University political science professor Robert Alexander:

They don’t anymore. Trump has taken the importance of what state you are voting in and flipped it. The public now thinks of supporting him or being against him nationally, not what their state interests might be. It’s no longer a question of what the candidates might do for their states. It’s who the public is aligning with.

Trump transcends geography; that much is true. But there is another factor at play. With Trump’s legal problems mounting, a large portion of the undecided voters in swing states are getting tired of his constant “persecution” message—and of him. Anecdotally, I can attest to this pattern in the Midwest, specifically in the suburbs.

So the states will matter, but not in the way they used to.

THE SOURCE OF THE CONFUSION may be that our method for electing presidents is slightly complicated, and even slightly complicated is too complicated for most of the news media. Commentator Al Hunt recently examined national presidential polls from 1991 through 2019 and compared their results to who won the presidency in that time period—but he included only national polls. He made no mention of the Electoral College results. For example, incumbent president Bill Clinton failed to get 50 percent of the national popular vote in the three-way 1996 election, but he won easily with 379 Electoral College votes.

There’s still value in national polls for gauging the mood of the country—and, for the media, for attracting eyeballs in the 43 or so states that aren’t competitive in presidential elections. But at this point, about 17 months from the next election, it’s time to start paying closer attention to the state polls.

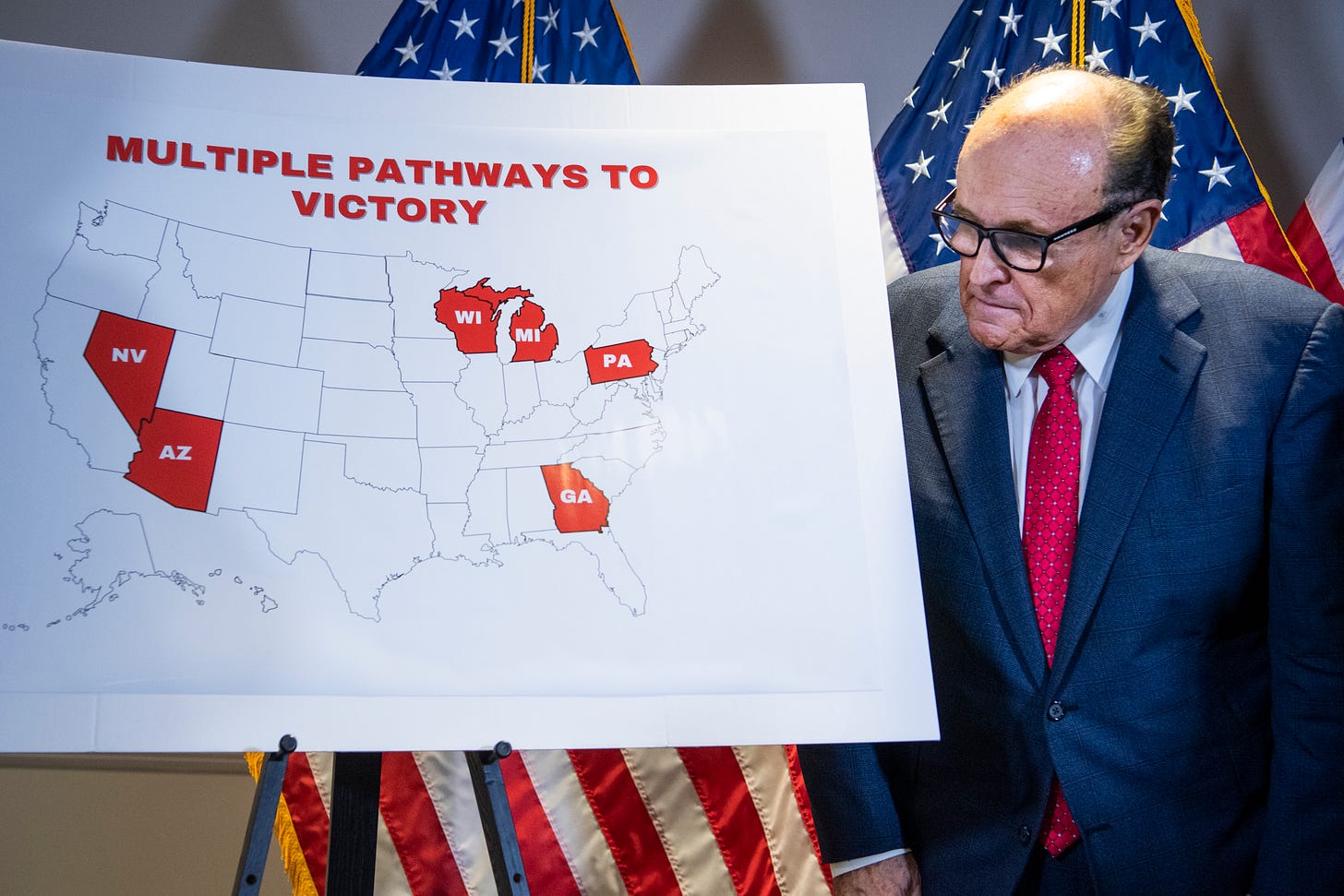

Barring something truly bizarre, Biden will win again if he wins the “blue wall” states of Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin in 2024. Those states together have 46 electoral votes. With those three states, plus every reliably Democratic state in his column, Biden needs just one addition Electoral College vote to reach the magic, winning sum of 270. He could clinch it by taking Nebraska’s 2nd Congressional District or Maine’s 2nd Congressional District—those states’ electoral votes are awarded a-la-carte by district rather than on a winner-take-all basis for the whole state—or by winning any one of the other swing states.

While Trump narrowly beat Hillary Clinton in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin in 2016 and won, Biden flipped them fairly easily in 2020. Biden could have lost Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada and still have accumulated enough Electoral College votes to beat Trump. And all three “blue wall” states voted overwhelmingly for Democrats in the 2022 midterms.

The current polls show Biden up by an average of 3.4 percent in those three Midwest states (based on an aggregation of 24 individual states polls, all done before the latest indictment). That tells a very different story from the RealClearPolitics average of national polls, which has Trump up by two points.

Pollsters insist that national political and cultural phenomena like QAnon (remember that?), “wokeness,” gender issues, and affirmative action can be measured nationally but not statewide. Sure. But notice: None of those measurements is related directly to an election.

Where elections are involved, there’s only one case in which national polls might be even slightly predictive of individual results: contests for seats in the House of Representatives. But for now, the House still has too many competitive districts to poll each one. Moreover, members of Congress are chosen based on who gets the most votes, which is not how we choose the president. Pretending that close national polls between Trump and Biden mean that the race is close is like a sportscaster insisting that a football game is close because one team has 300 total yards and the other has 275—even though the score is 31 to 10.

For a more concrete example, consider abortion. The overturning of Roe v. Wade was a major issue in the 2022 midterms, and projections suggest it will be again in 2024. National polls indicate that about 63 percent of women favor abortion being legal in all or most cases, compared about 58 percent of men. One could take this information and run all sorts of statistical operations about the percentages of male and female voters in the electorate and how they’re likely to vote, but it would be of little use. Figuring out how the abortion issue might influence who will be president in 2025 requires understanding the differences between male and female voters in different states.

Women vote much more than men, and that difference in swing states might be enough for the Democrats and Biden to win some states more easily than in 2020. Women in general out-vote men by about 53 percent to 47 percent.

In the swing states, the differences in women voting (based on 2020 registration numbers) is likely to be big: There are about 238,000 more female voters in Michigan than men; 372,000 in Pennsylvania; and 187,000 in Wisconsin. Looking beyond those three key states, the difference is 527,000 in Georgia; 343,000 in Arizona; 410,000 in North Carolina; and 53,000 in Nevada.

In 2020, before the end of Roe, Biden won Arizona by about 10,457 votes, or about 0.4 percent of the statewide total. Very close. The registered voters in Arizona are 54.6 percent women. Assuming abortion is a major issue in 2024, as it was in 2022—and the Biden campaign will probably do everything it can to ensure that—it’s not difficult to see who gets the advantage in Arizona.

Of course, polls are always snapshots. They can’t predict the future; they only offer imperfect, cropped images of the present. They’re always at least a little bit blurry. But there are better and worse ways to use them. National polls suggest that Trump may have an advantage in winning the national popular vote if the election were held tomorrow. But swing state polls suggest that Biden’s position is much stronger.

Daniel McGraw is a freelance writer and author in Lakewood, Ohio. Follow him on Twitter @danmcgraw1.