New Opera Gives Voice to the Pain of Gun Violence

An interview with Arne Duncan, the former education secretary whose work in Chicago is the basis for ‘The Walkers.’

There’s a moment in a new opera when a man sings, “I shot him one time. Watch y’alls’ selves. Cause. It’s hard to be human again.”

He’s just returned from prison after serving time for killing a man. He was 17 when it happened. He didn’t hate the man. He didn’t mean to kill him. It was all about money.

The Walkers, the most urgent segment of a trilogy called Proximity, opened at the Lyric Opera of Chicago on Friday, and it’s not the usual fare. Like many operas, it is tragic, but not because of doomed heroes or heroines like Don Giovanni or Madame Butterfly. It’s not even about mass shootings that make headlines. It’s about urban neighborhoods plagued by gangs and gun violence, and the gritty work of turning around one life at a time.

Audiences might recognize the unsettling “earth-changes” of Night, which addresses climate change. They’d surely identify with the modern couple in Four Portraits, attempting communication on a bad phone line, a crowded train, a GPS-disrupted car trip, and, finally, freed from technology, in a forest.

The Walkers is different. Most people, including me, have never met anyone in these circumstances. There is, however, one possibly familiar character. Arne Duncan has played professional basketball in Australia and pickup basketball with Barack Obama. He’s led the U.S. Department of Education, the Chicago Public Schools, and a couple of nonprofits. Now, and most unexpectedly, a singer is playing him onstage.

When I interviewed Duncan nine days before the world premiere of Proximity, I had read an advance copy of the libretto and neither of us had seen the production (I still have not).

“I have more than a little trepidation,” Duncan told me then. “I have to confess I have never seen an opera. I’ve never been to the opera. So being a character in an opera was not on my bingo card.”

Yet being a character in an opera could be his chance to help heal a city, and maybe even a country. “I don’t want to stereotype, but my sense is that 95 percent of people who would go to an opera performance probably don’t spend a lot of time in the neighborhoods where we work,” Duncan says. “So if we can be a bridge between these two worlds, that would be extraordinarily powerful.”

There’s a constellation of famous names attached to this opera trilogy about human connection, including director Yuval Sharon (a MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” recipient) and, for The Walkers, librettist Anna Deavere Smith (another genius grant recipient, perhaps most widely known for her acting career, which included long stints on The West Wing and Nurse Jackie). The score, by eclectic Haitian-American composer Daniel Bernard Roumain, ranges from hip-hop and rock to the lamentations of a community in agony.

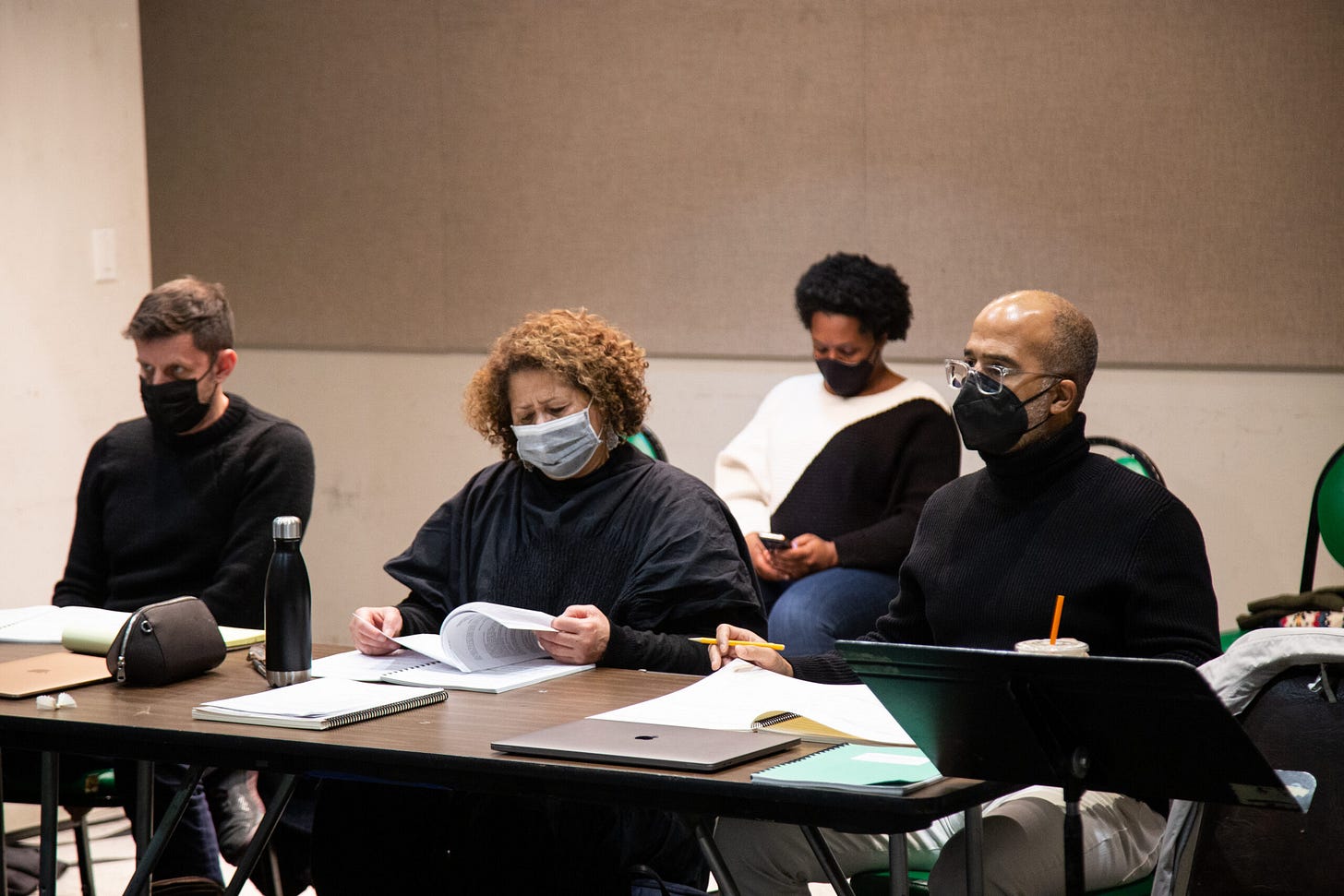

Yuval Sharon (left), the director of ‘Proximity,’ with Anna Deavere Smith and Daniel Bernard Roumain, the writer and composer of ‘The Walkers.’ (Courtesy of Lyric Opera of Chicago.)

This project was sparked by opera star Renée Fleming, special projects adviser to the Lyric, who had seen Notes from the Field, Smith’s documentary-style 2015 play about the school-to-prison pipeline. Fleming “invited me to write a libretto about gun violence in Chicago,” Smith says in a video, and an opera was born.

Enter Arne Duncan. When he was Obama’s education secretary, he was among some 250 people Smith interviewed for Notes from the Field. In 2016 he co-founded Chicago CRED (Create Real Economic Destiny) with Laurene Powell Jobs, president of the Emerson Collective, to work directly with those most at risk of being shooters or being shot. Smith went back to Duncan for another talk and ended up with The Walkers.

Using composite characters and verbatim interview transcriptions of Duncan, his CRED colleagues, and others, Smith word-paints a window on true-life anguish and devastation: the separate shooting deaths of a 9-year-old and a toddler, the gunfire threat hanging over funerals, the post-traumatic stress of the man who unintentionally killed someone at 17.

Why the “walkers”? Because they walk the neighborhoods, the funerals, and the cemeteries. Why do they do it? Why does Duncan do it? “Ain’t safe to be a white savior, dude. Ain’t you got sense ’nough to fear? Man—what are you doing here?” a young man asks onstage in the opera. To which “Duncan” replies, as the actual Duncan told Smith, “I’m here. Because you’re here.”

That’s proximity, and it’s courage.

Chicago CRED’s intensive program involves street outreach, therapy, life coaching, education, job training, even getting people out of town during Chicago’s traditionally violent holiday weekends. Rev. Craig Nash, CRED’s director of community engagement, portrayed as “Preacher Man” in The Walkers, had seen part of a rehearsal the week we talked. He and Duncan trusted Smith, he told me, but still, “I was wondering how it would translate to an opera.” Nash got his answer at the rehearsal. “They captured so much of our work,” he said. “Parts of it brought me to tears. People that see it will get it.”

One question is how many people will see The Walkers, either as part of the spliced and interwoven Proximity trilogy or on its own. Nash says he wants it to spread all over the country. That’s what happened with The Laramie Project, a much performed play that, borrowing Smith’s method, synthesized over 200 interviews conducted after the 1998 murder of gay college student Matthew Shepard. And there’s always the chance that, like Notes From the Field and Twilight: Los Angeles, two of Smith’s plays, The Walkers could have another life—and a mass audience—as a film.

Art with a cause can be too heavy-handed to be good art or even effective art. But the best art can illuminate social injustices and common humanity, emotionally engage people, and leave them pondering connections between causes and effects—no sledgehammer necessary.

The Walkers is dramatic, but it’s also fact based and acutely personal. There’s no political call to arms or action. There is mostly pain and regret. “You can’t be human and not be touched by what’s being presented about true stories,” Nash told me. On a recent visit to CRED, he added, some performers said the heart-wrenching material had made them break down during rehearsals.

Early reviews of Proximity have been mixed but generally positive. “Audacious, topical and thrillingly contemporary,” is how the Chicago Sun Times started off. It’s not unreasonable to hope that The Walkers in particular will touch its audience, giving them insights into children Duncan describes as choosing the only rational option available when, for instance, their mother cries because there’s no money to feed her children. They’re 9 years old or 12 or 13, and their younger siblings are hungry. They go out and get hired by the guy on the corner, because he’s the only one hiring. “You don’t judge,” Duncan says. He calls it the most important lesson he’s learned.

There are so many hopes one could invest in The Walkers and the real walkers, Duncan and his colleagues and allies across Chicago and America.

Crime is a potent political weapon in America, a way to scare people and pit them against each other: cities versus suburbs, rich versus poor, red states versus blue. But it’s possible to envision the kind of work Duncan does, the work that’s dramatized in The Walkers, as a way of humanizing people caught up in gun violence as both shooters and victims, to drive home the point that they are worthy of redemption and opportunities to change their lives.

This is a vision that cuts across ideology in unconventional ways. Redemption in the religious and practical sense became a life’s work for the late Chuck Colson after he served time for a Watergate-related crime. The website for the Prison Fellowship he founded describes him as “Richard M. Nixon’s White House counsel and hatchet man” and the Fellowship as “the world’s largest family of prison ministries.” Second chances are central to its mission, and in April 2017 the group launched a national annual Second Chance Month.

These themes are also important to Charles Koch, the billionaire funder of conservative and libertarian causes. He is famously committed to prison reform, rehabilitation, and an equitable justice system, as well as economic and educational opportunities that help people fulfill their potential. In 2020 he helped win passage of the bipartisan First Step Act that reduced federal drug sentences and made other changes to help reduce mass incarceration.

No liberal, progressive, or moderate would argue with these objectives. At the same time, there’s plenty of disagreement between and within both parties on how far and how fast to go, and the appropriate role of government in addressing the underlying conditions that can stunt lives and lead to bad choices. President Joe Biden’s failed attempts to renew a larger child tax credit and pass free preschool are cases in point.

The really tough part, though, is sustaining public interest, support, and pressure to make things happen. I once calculated I had written at least 17 columns on gun violence in seven years. That was in 2017, and I’ve written at least five more since then. Every time I’ve tried to find a new angle, a new way to engage readers, in hopes of connecting with more of them.

Yet these pieces came almost entirely in the aftermath of shocking gun rampages and mass death. It’s much harder to keep a spotlight on daily neighborhood violence that swallows up individual lives and can end them, too. The Walkers, so painful and personal, could help. Especially because it ends on an ever so slightly uplifting note.

Nash and Duncan say that’s realistic—that they could not do this work if not for the success of the many young people open to their program and a new path forward. If not for joy. There’s wonder in Duncan’s voice as he talks about two CRED graduates in good jobs, advancing and getting raises and helping others in the program find their way to employment and good decisions. When Duncan met them, one was “very, very heavily street involved,” and the other was serving time in the county jail. The potential was always there, he says, waiting for conditions that would allow it to flourish. The talent, the heart, the leadership was always there. And now both are life coaches for others.

“We deal with way too much trauma and heartbreak,” Duncan says, but there’s also “hope, inspiration, and transformation.”

Can art change hearts? It’s worth hoping the answer is yes.