‘Nineteen Eighty-four’ With a Female Face

Sandra Newman’s take on the George Orwell classic transcends its feminist critiques.

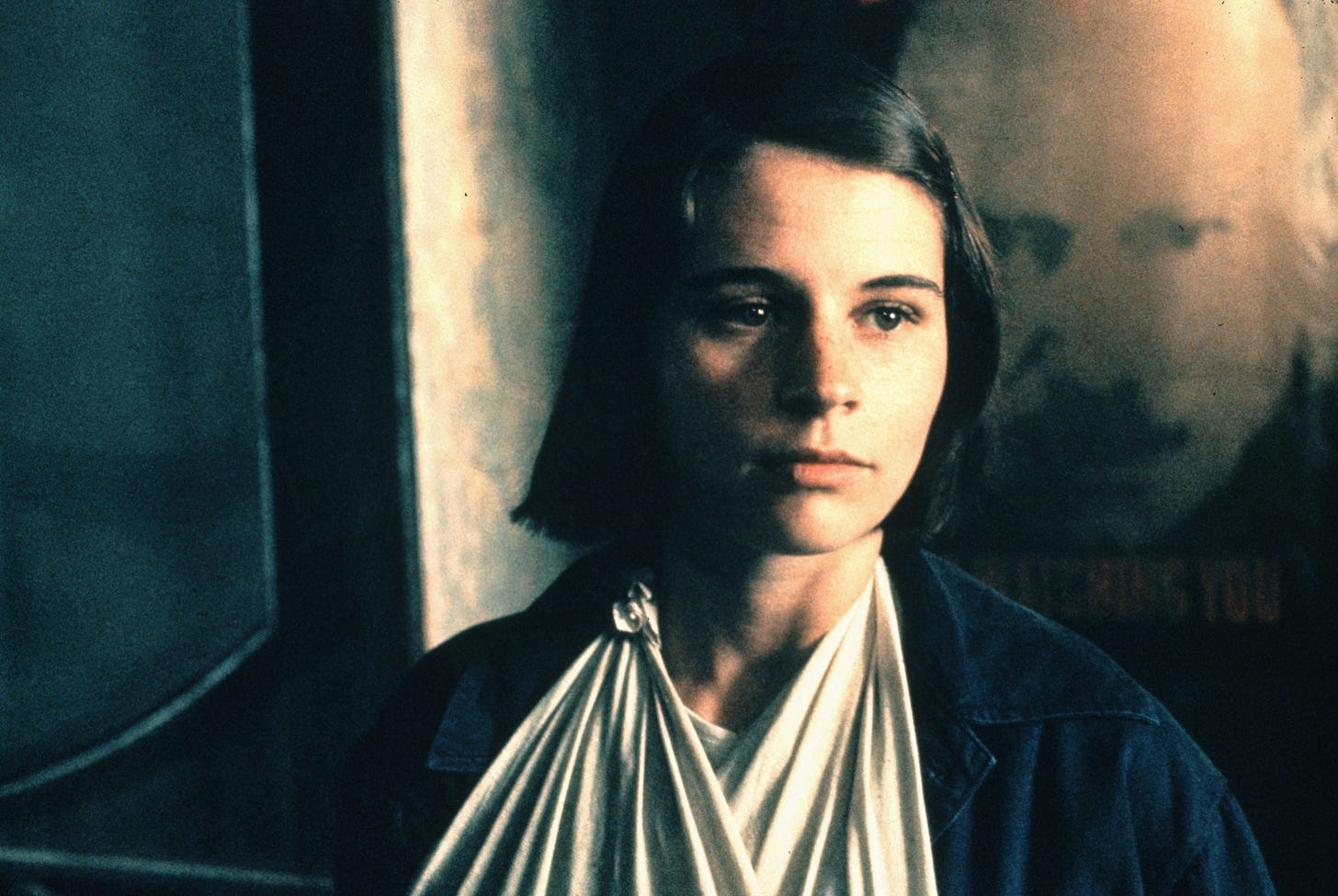

Julia

A Retelling of George Orwell’s ‘1984’

by Sandra Newman

Mariner, 385 pp., $30

FICTION THAT REIMAGINES CLASSICS from a different point of view—fan fiction, essentially, albeit somewhat more respectable than what that term usually denotes—has a long pedigree. You could make the case for Paradise Lost being the great-great-granddaddy of the genre. Notable modern examples include Tom Stoppard’s play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, which focuses on Hamlet’s hapless school chums; Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, which rehabilitates the attic-dwelling mad wife from Jane Eyre; and Gregory Maguire’s Wicked, in which the witch from The Wizard of Oz gets a name and a story. Now, George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-four, that greatest of twentieth-century political dystopias, joins the ranks of classics retold with Julia by Sandra Newman, published late last year. It’s an imaginative and well-written, if not always satisfying, complement to its source.

Julia also belongs to the recent tradition of feminist retellings—in this case, of a work often criticized for its treatment of women. Newman herself has told the Telegraph that she once “absolutely idolized” Orwell but later came to see his fiction, and especially Nineteen Eighty-four, as steeped in “hatred of women [that] is really extreme.” That’s debatable: Some argue that Orwell’s feminist critics wrongly conflate protagonist Winston Smith’s hostility toward women (explicitly acknowledged in the book and clearly shown to be rooted in totalitarianism’s monstrous warping of human relations) with Orwell’s own attitude. One could point out that Winston’s vision of humanity unwarped by the Party and its ideology is connected primarily to women—his own vanished mother, the “prole” woman singing as she does her laundry—and that his betrayal of Julia marks the point of no return in his own dehumanization and surrender.

Still, there is no question that women in Nineteen Eighty-four, like everything else, are seen only through Winston’s eyes. Julia (authorized by the Orwell estate) fills some gaps by taking us not only inside the mind of Winston’s free-spirited lover but behind the scenes to look more generally at the female side of life in Oceania, the one-party superstate that has replaced England.

In Nineteen Eighty-four, the Party seeks to tightly control sexuality by limiting acceptable sex to married, strictly procreative intercourse in which the wife is not expected to take any pleasure and branding everything else “sexcrime”; young adult Party zealots, women especially, are recruited into the “Junior Anti-Sex League,” which advocates total celibacy and procreation through “artsem,” or artificial insemination. Julia plausibly reveals that this anti-sex ideology coexists with the pervasive sexual exploitation of young women, including League members, by senior Party men; “artsem” is, more often than not, a hasty alibi for a pregnancy resulting from these liaisons. A particularly memorable segment of the novel early on, before the start of Julia’s relationship with Winston, chronicles a scandalous incident at the dorm she shares with other young Party women. Fixing a blocked toilet, Julia discovers that the cause of the blockage is an aborted fetus someone has attempted to flush down; the culprit turns out to be Vicky, the young and naïve “baby” of the dorm who has been given abortion-inducing pills by the Party official she’s been involved with. Then, in a fitting postscript to this episode, another dorm resident is hauled away as the transgressor.

Newman gives Julia a grim backstory as a child in a rural “semi-autonomous zone” (SAZ) in the early years of Ingsoc (English Socialism). The daily “Two Minutes Hate” is introduced by Party activists; with no telescreens, this consists of someone “reading the day’s hate column from the Times while the workers shrieked in rage.” A school play in which Julia gets a bit part inculcates the worship of Big Brother and the idea that compassion is a crime; it is punctuated by shots coming from a nearby field where executions are being carried out. (Nevertheless, life goes on, and local teen girls still moon over the well-groomed city boys who arrive in the village as volunteers teaching Party doctrine—even if the doctrine includes condemnations of the evils of sex.) Things get much worse when Party policies meant to put agriculture “on a rational basis” result in hunger, and state terror against “bourgeois-capitalist conspirators” escalates. Newman’s gritty, unsentimental description will sound familiar to anyone who knows the history of real-life attempts to build Communist utopia:

Other villagers abused the arrestees, cursing them as wreckers and parasites, and laughing sycophantically when one was beaten. This was not a matter of belief. It was because, if enough enthusiasm was shown, the Party activists gave out bread.

The backstory has a harrowing denouement. Julia’s mother, Clara, tells her teenage daughter that that everyone in the village is doomed, but Julia still has a way to save herself—by denouncing her mother. (Clara, once a resident of Oxford, has some past connections to old revolutionaries now branded traitors; this makes her valuable as a potential enemy of the people who can be blamed for engineering the famine.) Julia does as she is told, and lives.

While those parts of the novel are entirely original and compelling, much of the narrative presents Julia’s side of the story we already know: her clandestine relationship with Winston; their meeting with O’Brien, who poses as a member of the resistance underground but turns out to be a Thought Police agent; their arrest and ordeal in the “Ministry of Love” (its remit includes torture and executions, one of many darkly funny ironies of Oceania’s dystopian state); their release after both are broken; their sad encounter afterward. Newman gives this story some new twists, one or two of which are significant enough to change the meaning of some key interactions; to say more would spoil a dramatic part of Julia’s plot.

Some of the alternate narrative is genuinely funny and adds a clever footnote to familiar details. (Remember the part in Nineteen Eighty-four where young women from the Junior Anti-Sex League are tasked with writing cheap porn for the proles because the Party believes they’re too pure to be corrupted by it? Well, Julia reveals that they’re not: The effects of their work include a lot of furtive self-gratification.) Some of it is moving and even heartbreaking, such as Julia’s mostly platonic relationship with the neurotic middle-aged poet Ampleforth (who appears in Orwell’s original but is not shown to have any connection to Julia) and her failed attempt to help him escape arrest by committing suicide.

But this new material is also quite uneven. Several passages in which Julia argues with Winston or silently scoffs at his opinions read like a heavy-handed attempt to knock Orwell’s hero off a nonexistent pedestal; a passage in which she reflects that Winston’s description of his estranged wife Katherine as a mindless, sexless Party drone may not be entirely true since “the wife wasn’t there to give her side” feels like especially blatant editorializing. A storyline involving Julia’s officially sanctioned pregnancy, supposedly via “artsem,” seems pointless and far-fetched, especially when we’re expected to believe that the Ministry of Love torturers who do horrific things to Julia are careful not to harm the fetus. Surely being subjected to excruciating pain and threatened with face-eating rats (yes, those rats) could cause a pregnant woman to miscarry even if none of the violence directly targeted her belly. As for Newman’s take on the rats—without spoiling the outcome, I will say that I found it particularly implausible and more gross than horrifying, in stark contrast to Orwell’s spine-chilling nightmare.

An epilogue of sorts in which Newman’s narrative continues past Orwell’s feels more fresh and inventive, holding out the hope of liberation—but offering an ambiguous ending with a genuinely startling turn far too interesting to give away. It’s a bit reminiscent of the implied cliffhanger at the end of the heroine’s narration in Margaret Atwood’s A Handmaid’s Tale, but in a way, it also echoes the ambiguity in the ending of Nineteen Eighty-four, wherein Winston may or may not be dead.

IF JULIA IS INTENDED to right Nineteen Eighty-four’s alleged wrongs toward women, I’m not sure it succeeds. It certainly fleshes out women’s lives under Ingsoc in a richer way than Orwell’s novel does. Whether it gives Julia more “agency,” as some critics have claimed, is very much an open question: She has plenty of agency in Nineteen Eighty-four. Newman’s version of the character doesn’t really depart from Orwell’s depiction of Julia as someone whose rebellion against the regime is primarily sexual, not intellectual. Indeed, this feminist revisioning could itself be accused of misogyny, if one were so inclined: For instance, Julia’s molestation by a middle-aged Party member at the age of 14 is treated as an experience that at times repels her but is ultimately pleasurable, wanted, and even liberating. It’s not clear to me that we can draw a bright moral line between Newman’s depiction of this offensive scenario and Orwell’s depiction of his protagonist’s offensive misogynistic thoughts, praising the former while roundly condemning the latter.

In her remarks to the Telegraph, Newman indicts Orwell as a misogynist or, at the very least, someone who regarded women as too unimportant to put at the center of a novel—a dubious claim considering that his second novel, A Clergyman’s Daughter, has a female protagonist who struggles to escape the repressive confines of her life. One reviewer in a major newspaper not only amplifies this indictment but asserts that Julia is better than the original and should replace it in the canon of English literature.

Thankfully, one doesn’t need to accept such claims to read and enjoy Julia both as a novel in its own right and as a companion piece to Orwell’s great novel. And it invites us to revisit the nightmarish world of Oceania at a cultural moment when far too many men and women across the political spectrum are disposed to rail against thoughtcrime, memory-hole inconvenient facts, and participate in political hatefests.