No True Believer

Margaret Atwood’s look back at her life and career shows readers that building and maintaining an independent mind is a full life’s work.

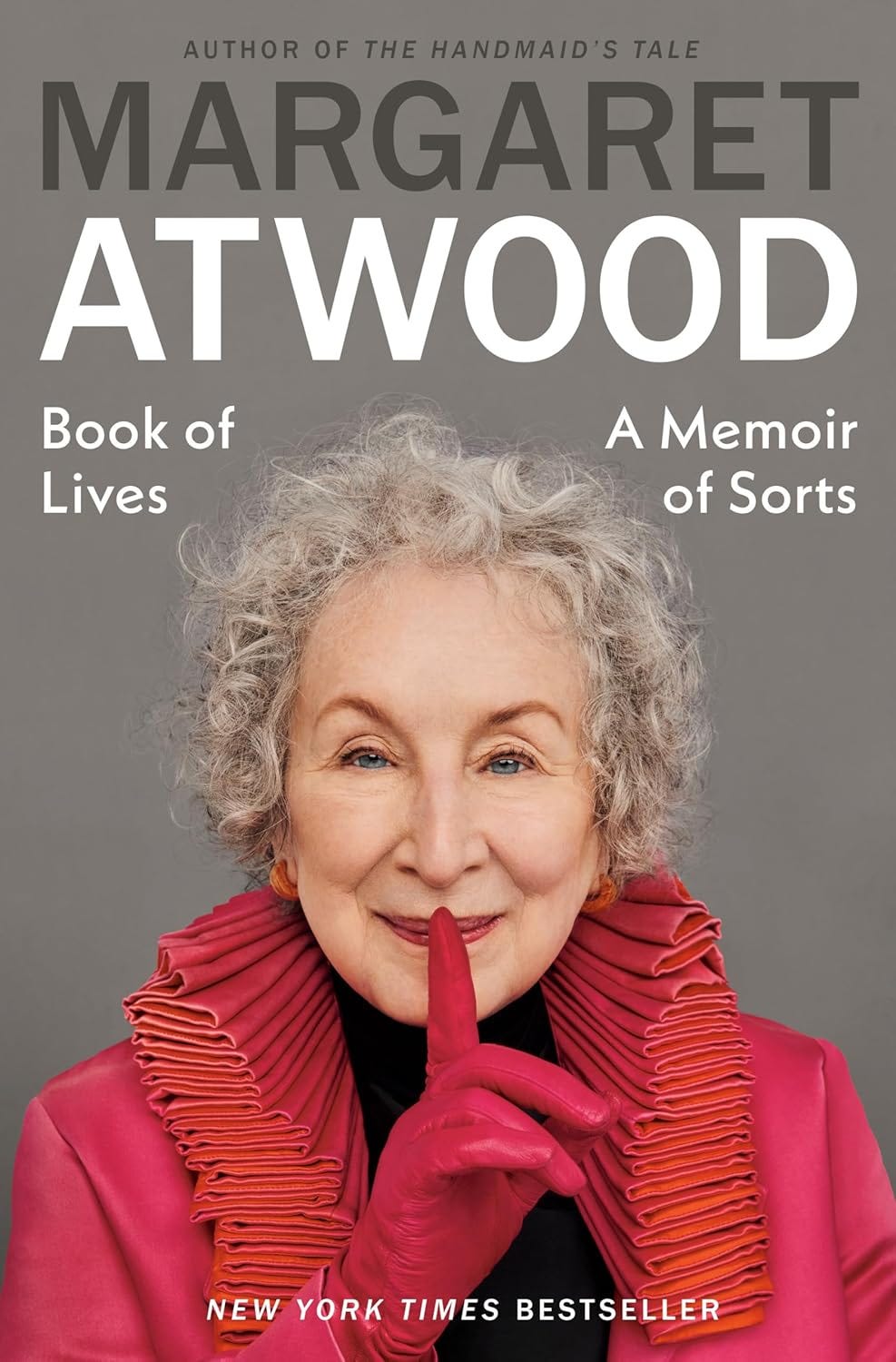

Book of Lives

A Memoir of Sorts

by Margaret Atwood

Doubleday, 624 pp., $35

SHE LIKES BAKING. SHE FOUND meal ideas in The Joy of Cooking. She made chocolate mousse for ten at a dinner party the day she returned from the hospital after giving birth to her daughter. Facing the opportunities and demands of her professional life after becoming a mother for the first time, she found she “was just not very interested: the baby was much more important.” She also observes, based on her personal experiences with a childhood frenemy, that “Anyone who thinks that females are perfect, that girls are nicer, that every sadistic thing girls and women do is the fault of ‘the patriarchy,’ has either forgotten a lot or never been a nine-year-old girl at school. . . . Grown men can be as Machiavellian as nine-year-old girls, but boys haven’t quite learned how.”

This last observation I fact-checked with my wife and our four teenaged daughters. “Wow, clock it” was the immediate and then emoji-affirmed response in the Boyagoda Family Chat.

In recounting her life and work as a celebrated and influential writer, Margaret Atwood can come across as unexpectedly at ease with perceived trappings of traditionally coded femininity, and likewise, as willing to pick out and criticize elements of contemporary progressive feminism. This might seem to place her at odds with her status as world-famous feminist icon, but the two-time Booker winner resists ideological categories, living and working across the full, free range of her imagination and curiosity.

Of course, she’s more than willing to level criticisms in a rightward direction. Indeed, partway through her formidable, funny, and moving new book, she wonders if it really is true that what she wrote created millions of “scared men worried that I would go full Salomé and decapitate them? Were they that insecure?”

Atwood has long been feared and praised as a feministe terrible and icon both. Her best-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), was adapted into a TV series in the early days of the first Trump administration, and the buzzy success of the adaptation transformed the public’s view of her. She came to be seen as something of a wry laureate of the MAGA era and a prophetic chronicler of its regressive, patriarchal politics and its policies that openly militate against women, their rights and bodily autonomy.

She uncannily anticipated these features of our present moment—and yet the most striking feature of Book of Lives is Atwood’s fundamental recalcitrance, informed by disposition and experience both, to being made into a one-dimensional figure of any kind, whether as a hero of the resistance, a crypto-reactionary, or any other stock type.

Atwood’s qualified memoir—signaled with that “of Sorts” in the title—proceeds as both a reflective chronicling of her life and career and also as a meditation on what it means (and takes) for a writer to tell her own story. “I’ll have to describe the features of my own time-spaces if I wish to cast any light on this writing thing,” she tells us. Therefore, “Be prepared for descriptions of outmoded technologies, such as ice houses and milk cupboards, and for explanations of archaic social rituals, such as sock hops and going steady. Also for thumbnail sketches of fashions of the time, such as pantsuits, miniskirts, A-line dresses, and the Ethnic Look.”

She starts with her parents, who came up in early twentieth-century Nova Scotia. (Some of her family history on the continent goes to the Puritans.) Atwood’s father Carl was an entomologist who worked for the federal government. The family spent parts of every year in various research sites in the wilder and remoter parts of Canada, living in tents that gave way to rough cabins and log houses that Carl Atwood built largely on his own.

As is often the case with books by accomplished people who come from unlikely origins, the memoir’s stories of rustic or even hard-bitten early life, so far removed from later success and stardom, have a particular richness to them. Atwood’s imagination-forging childhood adventures aren’t soft: She gives us detailed accounts of how to gut fish and offers tips about when to avoid certain animals. (“Moose, dangerous in mating season.”) She recalls endless hours spent with friends in the deep woods around Lake Kipawa, in Quebec—a scenario it may be difficult for many parents today to imagine: “What were the grown-ups thinking? They would probably be arrested now for letting such young children wander around in the woods unaccompanied. But we knew how to follow the axe-cut blazes, and we never got lost.”

At this point, a lesser writer might go in for an extended rant against latter-day helicopter parenting. Not Atwood. She moves things along in short order to early postwar Toronto, where her family moved, and where Atwood has a memorably bad experience with a bullying band of fellow grade-school girls that decided to make her their plaything. It’s an experience that would inform several books, including her novel Cat’s Eye (1988).

Indeed, Atwood often points out the ways her varied life experiences have furnished material for her writing. This includes school days interleaved with family time in the deep Canadian woods; undergraduate studies in English at Victoria College at the University of Toronto and graduate studies in English at Radcliffe College at Harvard; peripatetic years of writer-in-residence and teaching appointments across Canada and the United States; and years of mixing it up with various other writers (as well as agents, editors, publishers, and film-makers) also on the make during her long rise.

And it was long: Atwood was sent to sign copies of her first book, The Edible Woman (1969), in front of the men’s socks-and-underwear section of a Hudson’s Bay department store in Edmonton. Around that time, she was also giving poetry readings in remote small-town school gymnasiums. During a sudden snowstorm at one of these events, she recalls having to “put my cardboard boxes [of unsold books] onto a sled and [haul] them to the bus station.”

The most entertaining segments of the book concern experiences at the rural Ontario farmhouse she bought with Graeme Gibson. After earlier marriages didn’t work out for either writer, Gibson and Atwood became lifelong partners. He was also a champion birder and literary evangelist for birding; his Bedside Book of Birds is equal parts learned, beautiful, and engrossing. (It also makes for an elegant gift.) In the early 1970s, Gibson and Atwood went to the country outside Alliston, Ontario to get away from the distracting temptations of big-city life.

No sentimentalist, Atwood gives us excellent episodes of Nature red in tooth and claw, including the tale of a rooster mad with worry and rampaging about to protect indifferent hens from lurking foxes. Raising animals, Atwood knows, requires a certain hard-mindedness. The family kept cows for a while, and Atwood and Gibson told Gibson’s sons (from his previous relationship) not to name them, just in case tough decisions had to be made.

The boys didn’t listen. After a cow is put down, Atwood writes, “Result: ‘Is this Susan we’re eating?’”

UNFLINCHING, MORDANT JOKES feature throughout the book. They come at the expense of dead cows and also petty writers and condescending, self-embarrassing men, particularly the sort who tell Atwood with enthusiasm that their wives love her novels. There’s also more serious matter, and it centers on two subjects: the origins and eventual renown of The Handmaid’s Tale, and Gibson’s decline and death in 2019, just before Atwood won her second Booker, for that novel’s successor, The Testaments. As a world-famous public person in private grief, she faced a stark question: “The busy schedule or the empty chair? I chose the busy schedule. The empty chair would be there when I got home.”

As for The Handmaid’s Tale itself, as much as many might like to believe she somehow predicted the moment in American history we associate so closely with Trump, Dobbs, MAGA, MAHA, TPUSA, InfoWars, Charlottesville, and “trad wives,” Atwood makes it clear in this book that even if she has a thing for Tarot cards and reading palms, she’s no prophet. In fact, she doesn’t have a single origin story for her most influential book. Its sources come from many places, all of them found in the world as she saw and experienced it growing up. They include Harvard’s campus, academic culture, and surroundings in 1960s-era Cambridge, Massachusetts; the experiences of women under modern theocratic regimes in Iran and Afghanistan; the rise of the Religious Right during Ronald Reagan’s first term; her reading of science fiction and dystopic stories by H.G. Wells, Ray Bradbury, John Wyndham, John Christopher, and, of course, George Orwell; Puritan-era America; and Cold War–era Berlin.

Partisan readers may be selective in what they choose to emphasize from this list, but the writer herself is not. What gives The Handmaid’s Tale its lasting coherence is neither politics nor ideology but instead an imagination both searing and humane. That said, Atwood goes on to observe that when the television adaptation of the novel “was still being shot in November 2016” before airing the following spring, “nothing in the script had changed,” but “the frame within which people would view it was now radically altered.”

Was Atwood herself influenced, creatively, by the way external political circumstances had altered and elevated her in the public eye? Trump does not seem to have played as a significant role as you might expect, at least as she chooses to tell the story. In truth, I would have welcomed Atwood’s reflections on her longstanding Canadian cultural nationalism and her public opposition to the first Canada–United States free trade pact in the early 1990s from the standpoint of our current nationalistic, protectionist era. Her decision not to address this stark volte-face is a lost opportunity for a welcome assessment of what’s stayed constant and what’s changed in her sense of economic-cultural nationalism.

Instead, she describes as instructive the experience of ending up on the wrong side of history when she offered a defense of Steven Galloway, an acclaimed writer and professor at the University of British Columbia who was accused of sexual assault and summarily fired from his academic position and cancelled from his publishing career. Atwood publicly and repeatedly called for due process for Galloway, eliciting angry attacks from younger and very online feminists. (The situation became so fraught for the Canadian literary scene more generally that many who were involved in either attacking or defending Galloway remain unwilling to talk about it publicly even a decade later. While Galloway himself was never criminally charged with sexual assault, his writing and teaching career ended with the scandal.)

The “deluge of smears, hatred, and misinformation” to which Atwood was subjected for her stance on Galloway taught her something useful: “I was experiencing at first-hand a pale version of what it’s like to live through an ideological clampdown.” She drew on the episode to develop one of the main characters of The Testaments; the character outwardly works for the regime in power, but she works against it in secret.

Atwood makes a point of noting that “unlike me,” this character “poses as a True Believer.” While the author has meant many irreconcilable things to many millions of readers, one thing she’s never been is that. And that’s what makes her books, including this one, worthwhile. Atwood’s work creates a little space for the head to think and heart to feel; her books reveal how the imagination—whether amusing, or dystopic, or searing, or humane, or all of these at once—may sustain us against ideological clampdowns and various other sad, sadistic things.

Randy Boyagoda is a novelist and professor of English at the University of Toronto. Lords of Serendipity, his first novel to be published in the United States, will appear in September 2026.