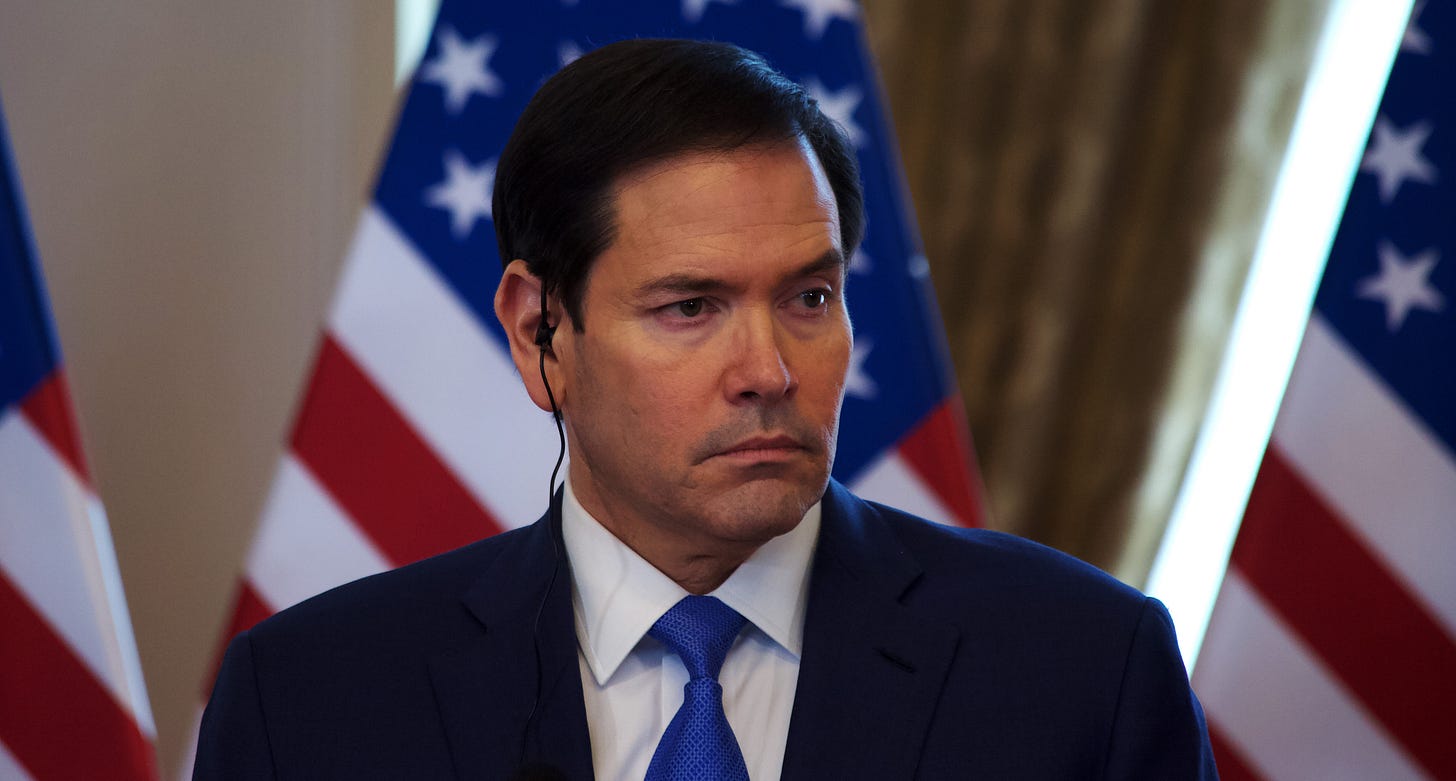

Rubio Offers Europe Trumpism With a Human Face

All the talk of friendship and partnership masked a deeper hostility.

LESS THAN A MONTH AFTER after the transatlantic crisis over Greenland, Europeans risk being lulled into a false sense of security. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s message to Europe, delivered to standing ovations at the Munich Security Conference, was one of “reassurance, of partnership,” said the conference’s chairman, Wolfgang Ischinger. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen was “reassured by the speech” coming from a “good friend.”

Europe’s partnership with the United States runs broad and deep—from defense and security, to trade and investment, to shared technological and financial platforms—and will continue to do so for decades, in part because there are few alternatives. Yet, as Trump’s first year back in the Oval Office shows, Europeans must double down on their efforts to derisk the relationship. It will be a costly, difficult, and long-term exercise. “Reassuring” speeches from the likes of Rubio may make that crucial endeavor more politically difficult.

Unlike Vice President JD Vance’s remarks last year, Secretary Rubio’s speech presented Europe with a Trumpism with a human face. He paid lip service to shared history and acknowledged the rationale for the transatlantic partnership. But beneath the veneer, his speech was not substantively different from Vance’s hostile message to Europeans, nor did it announce any meaningful departure from policies openly hostile to Europe’s interests.

For example, Trump’s new National Security Strategy vows to support anti-establishment right-wing and populist forces on the continent. Under Secretary of State Sarah Rogers might deny that the State Department has a “slush fund” for the European far right, but the secretary himself chose to visit two of the EU’s most noxious leaders, Slovakia’s Robert Fico and Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, immediately after his remarks in Munich. For her part, Rogers has a history of aligning with Europe’s extremists, including seemingly friendly contacts with Germany’s AfD.

In Rubio’s words, the United States “demands seriousness and reciprocity” because “we care deeply”—even as it charges a 15 percent tariff on EU goods in exchange for tariff-free access to the EU market and commitments of large-scale European investment and energy purchases.

Moreover, just like Vance last year, Rubio had no compunction about lecturing the Europeans on their supposed “delusions,” though acknowledging that those were once shared by America as well—“a dogmatic vision of free and unfettered trade,” the “climate cult,” or ceding “sovereignty to international institutions.” Some of his observations were valid (for example, that the growth of welfare states has hampered Europeans’ ability to invest in defense), while others were debatable (that “an unprecedented wave of mass migration . . . threatens the cohesion of our societies, the continuity of our culture, and the future of our people”).

For a member of an administration so emphatically committed to national sovereignty, Rubio evinced an abundance of opinions about how Europe should govern itself—and very little acknowledgment of Europe’s own interests. There was no sign of remorse about the grotesque, completely needless confrontation over Greenland. Should Europeans believe that such a thing could not happen again?

There is every indication that the Trump administration wants Ukraine to fold, consequences for European security be damned. With no financial or military aid from the United States beyond the 2024 supplemental, Europe now bears most of the cost of helping Ukraine, including commercial purchases of weapons that Ukraine needs. President Trump, who temporarily paused intelligence sharing with Kyiv last year, was clear last week when he said that “Russia wants to make a deal, and Zelensky is going to have to get moving.” Rubio’s tone in Munich may have been different, but the substance was the same. In his quest for “terms that are acceptable to Ukraine that Russia will agree to,” he omitted that such terms were not a function of the situation on the battlefield, which U.S. assistance to Ukraine, or further sanctions against Russia, could alter.

In a perverse way, for the sake of Europe’s future, it would have been preferable if the Trump administration had struck a more confrontational tone with Munich attendees. The figure of Rubio, flanked by senators and representatives of both parties, the delegation together exuding false normality and civility, makes it tempting for Europeans to believe that the continent can put Trump’s past abuses behind it and wait patiently for January 20, 2029.

In reality, though, Trump or no Trump, U.S. politics is likely to remain turbulent for years to come. The question of whether the United States would come to Europe’s defense in a time of crisis seems less certain than the question of whether the United States will cause another European security crisis. It is risky for European militaries to continue relying on American weaponry—46 percent of Europe’s fighter jets and 42 percent of its missile systems come from the United States—yet the U.S. administration treats NATO’s spending targets as an arms-export program.

Europe’s dependence on American payment systems, American assets, and American software are equally problematic, if one accepts the possibility that this or a future U.S. administration might choose to weaponize them against its allies. It’s also increasingly evident that preserving democratic governance in Europe is going to require the EU to make deep regulatory changes to the operation of (mostly American) social media platforms.

Addressing these vulnerabilities is a massive, long-term challenge—all the more so since it requires reversing the trend of Europe’s entire post-1945 history of greater interdependence with the United States. Of course, no one wishes for the relationship to break down completely. It would be far worse, however, for Europeans to allow the current dependencies to continue—or even deepen. Hoping that the current détente will not be followed by renewed unpleasantness is not a strategy.