Supreme Court Opens the Door to Future Cases About Religion in School

Siding with a high school football coach who prayed with students, the conservative justices toss out the ‘Lemon test’ for evaluating Establishment Clause cases.

As part of the flurry of end-of-term decisions that included overturning Roe v. Wade and striking down New York’s strict concealed-carry gun laws, the Supreme Court also issued a 6-3 ruling last week touching on state establishment of religion. In Kennedy v. Bremerton, the Court sided with a football coach who claimed he was unjustly fired for praying at midfield after games. The American Civil Liberties Union deplored the ruling as “deeply disappointing” and said that it “significantly erodes the separation of church and state in public schools”; conservative groups hailed it as a victory for the First Amendment.

The ruling in this case is not the endorsement of theocracy, or even of extensive church/state entanglement, that its critics fear it is. True, the court explicitly jettisoned the traditional “Lemon test” (based on the 1971 Lemon v. Kurtzman case), which held that the state’s conduct in Establishment Clause cases must have “a secular purpose,” must neither advance nor inhibit religion, and must not “foster excessive government entanglement with religion.” The test has been riddled with problems of subjective interpretation from the start and was arguably reduced to irrelevancy over the years. However, the implications of Kennedy v. Bremerton for determining what practices may cross the line into religious coercion are unclear because of the peculiar nature of the case, which rests on a hotly disputed narrative. “The first and most important thing to realize is that the outcome in this case, more than the specific reasoning, is very closely tied to at least what the majority viewed as the facts,” UCLA law professor and blogger Eugene Volokh, who specializes in First Amendment law, told me in a telephone interview.

Here’s how Justice Neil Gorsuch summarized those facts in the majority opinion:

Joseph Kennedy lost his job as a high school football coach because he knelt at midfield after games to offer a quiet prayer of thanks. Mr. Kennedy prayed during a period when school employees were free to speak with a friend, call for a reservation at a restaurant, check email, or attend to other personal matters. He offered his prayers quietly while his students were otherwise occupied. Still, the Bremerton School District disciplined him anyway. It did so because it thought anything less could lead a reasonable observer to conclude (mistakenly) that it endorsed Mr. Kennedy’s religious beliefs.

Others, including Justice Sonia Sotomayor in her scathing dissent, see a very different chain of events—one in which the Bremerton School District, which serves over 5,000 students in Kitsap County, Washington, repeatedly tried to accommodate Kennedy despite his increasingly public religious demonstrations, and finally ran out of patience after one of his postgame prayer sessions turned into a chaotic melee joined by a throng of spectators and witnessed by journalists.

This Rashomon-like clash of narratives is also reflected in the press coverage. Vox’s Ian Millhiser writes that the majority opinion “relies on a bizarre misrepresentation of the case’s facts”; in National Review’s Bench Memos blog, Ed Whelan derides Sotomayor’s dissent as “shoddy” and based on “deceptive wordplay” and the deceptive use of photos. Much depends on which facts one chooses to highlight. As in the parable of the blind men and the elephant, some commentators have grasped the trunk and said the elephant is like a snake, while others have touched the leg and concluded that it’s a pillar. Let’s do our best to step back and behold the elephant in full.

Joseph Kennedy, hired in 2008 as an assistant coach for Bremerton High’s varsity team and head coach of the junior varsity squad, began his midfield prayers as a private activity; he says he was inspired by a 2006 Christian movie, Facing the Giants, in which the coach of a failing high school football team turns things around by praising the Lord on the field. (This is a very postmodern case.) At some point, some of the players “asked whether they could pray alongside him,” Gorsuch writes. “Mr. Kennedy responded by saying, ‘This is a free country. You can do what you want.’”

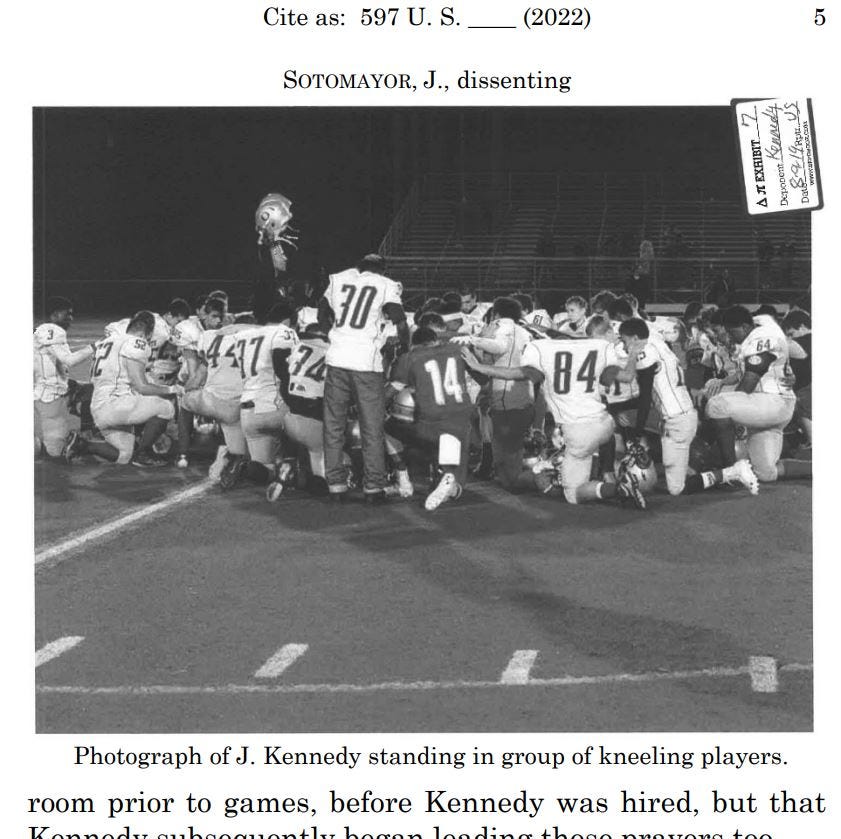

Eventually, “most of the team” was participating, “at least after some games.” The postgame prayer evolved into a ritual in which Kennedy would deliver inspirational coaching speeches with “overtly religious references,” sometimes holding up student helmets while students knelt around him. Justice Sotomayor inserted a photo of one such instance as an illustration in her dissent—one of three photos she included, an unusual move that promptly went viral:

Screenshot of a page from Justice Sotomayor’s dissent.

Student participants sometimes invited players from visiting teams to join in the postgame prayers. And it wasn’t all after games: There were brief locker-room pregame prayers (a practice that antedated Kennedy’s tenure) that he would sometimes lead. There is no indication in the record that the prayers were sectarian; last April, Kennedy told ESPN, “It was really a simple thing. I’d say, ‘God, thank you for these guys and the opportunity to coach them.’”

Many spectators apparently didn’t realize they were witnessing a group prayer; many thought it was just a huddle to raise team spirit. Some parents, ESPN reports, were not happy when they found out it was a religious exercise. Nonetheless, “for over seven years, no one complained to the Bremerton School District about these practices,” Gorsuch writes. Then, in 2015, an opposing team’s coach mentioned to Bremerton’s principal that Kennedy had invited his team to join in a postgame prayer. As the Bremerton High School principal later recalled, the visiting coach thought it was “pretty cool how we would allow our coaches to go ahead and invite other teams’ coaches and players to pray after a game.” That was the first time the principal had heard about the prayers. He and officials from the school district immediately had concerns about the constitutionality of what was going on. According to the school district’s brief,

Before the September 11[, 2015] game, Bremerton’s athletic director instructed the coaching staff to end the prayer practice. . . . When Kennedy delivered a prayer after the game anyway, he saw another coach shake his head in disapproval. . . . That evening, Kennedy posted on Facebook, “I think I just might have been fired for praying.” . . . His posting led to an “explosion in calls and emails” to the District.

On September 17, Kennedy received a letter from the school district superintendent, Aaron Leavell, informing him that his conduct violated the Establishment Clause. He could no longer lead locker-room prayers or mention religion in his motivational speeches to the team, and while he could still pray, he had to do it in an unobtrusive way so that it could not be construed as officially approved school activity and could not allow students to join in. (They could conduct their own prayer, but it had to be separate to avoid the impression that it was being led by an authority figure.)

Kennedy initially complied with all of the district’s demands and kept his prayers on the field quiet and private, but after a few weeks he had a change of heart and informed the district that he had to resume the prayers and was not going to stop just because kids gathered around him. He hired lawyers and took his case to the media. After the homecoming game on October 16, the “quiet” prayer became a circus. According to Sotomayor:

After playing of the game had concluded, Kennedy shook hands with the opposing team, and as advertised, knelt to pray while most BHS players were singing the school’s fight song. He quickly was joined by coaches and players from the opposing team. Television news cameras surrounded the group. Members of the public rushed the field to join Kennedy, jumping fences to access the field and knocking over student band members.

As one of the student football players later described it, before the two teams could shake hands, more than five hundred people were “storm[ing] the football field . . . from both sides, hopping the fences and rushing to the field to be close to Kennedy before he started his prayer.” The student said he felt “unsafe”—a term often derided in recent years as conflating emotional discomfort with physical danger, but here likely meant in a literal sense.

Kennedy claims that he suggested to the school district that he could pray while the players were headed to the locker room or the team bus. The district strongly disagrees, claiming that

neither he nor his counsel ever informed the District of that; they never accepted any offered accommodations; and they never responded to the District’s repeated invitations to propose other accommodations that might satisfy Kennedy. Instead, they stood on their October 14 demand and press statements that the District must rescind its September 17 guidance and allow Kennedy to “continue his practice” of praying “audibly” with students on the 50-yard line.

The superintendent suggested in an October 23 letter that “a private location within the school building, athletic facility or press box could be made available to [Kennedy] for brief religious exercise before and after games,” and the principal told him that he could pray on the field after it had emptied. But he was ordered not to return to the field for another postgame prayer—partly because doing so conflicted with his other responsibilities, but partly for constitutional reasons, as the October 23 letter made clear:

Any reasonable observer [after the October 16 game] saw a District employee, on the field only by virtue of his employment with the District, still on duty, under the bright lights of the stadium, engaged in what was clearly, given your prior public conduct, overtly religious conduct. . . . Under federal court precedent, a court would almost certainly find your conduct on October 16, in the course of your District employment, to constitute District endorsement of religion in violation of the United States Constitution.

After Kennedy then conducted two more postgame prayers at the 50-yard line while the players were engaged in other activities—one in which he was solo, the other with a few members of the community joining in—the district placed Kennedy on administrative leave and then decided not to renew his contract.

The case briefly flared into the national political discourse, with candidate Donald Trump even tweeting about it in October 2015 to the nearly five million followers he then had. Thus began the process of litigation that would culminate with Trump’s three Supreme Court appointees joining the three other Republican-appointed justices to hand the coach his big victory.

In the end, the majority ruled on the question as framed in Kennedy’s petition: “whether a public-school employee who says a brief, quiet prayer by himself while at school and visible to students is engaged in government speech that lacks any First Amendment protection” or in private expression protected by the Free Speech and Free Exercise clauses of the First Amendment. Within that framework, Volokh says he is “inclined to think” that the Court’s ruling is correct—and not particularly radical, as precedent makes clear that the First Amendment allows a teacher in a public school to engage in personal religious expression (such as wearing a yarmulke, a cross or a Sikh turban on the job).

Sotomayor’s dissent agrees with the school district’s October 23, 2015 letter, insisting that Kennedy’s conduct on the last two or three occasions he prayed at midfield must be seen in the larger context of his history of leading group prayers and giving faith-inflected motivational speeches—and that seen in the light of his past conduct, continued prayers from him would amount to state-sponsored religious coercion, since he was interacting with students in his capacity as a coach at a public school.

Kennedy’s defenders (such as Whelan) pooh-pooh this reading of the facts, pointing out, for instance, that many of the students who joined Kennedy’s midfield prayer circle were from the visiting team and thus not under his authority. Yet if anything, one can argue that the two teams joining in prayer created more pressure on students to participate. Here too, the evidence is contradictory. Some students, according to the brief filed by community members, do claim they felt pressured to join in the prayers in order to remain football team members in good standing. Kennedy has said that when, in one season, two players strongly objected to the prayers, he made them both team captains because “I need leaders. I don’t need a bunch of drones on the field.” But that story is unconfirmed, and various accounts of Kennedy’s history of mixing coaching with religion make it plausible that he created an atmosphere in which group prayer was conducted under a quasi-official umbrella.

And yet before one dismisses Kennedy’s complaints out of hand, it is worth remembering that there is a history of aggressive and illiberal efforts to purge anything with religious themes from the school environment under a misguided reading of strict church/state separation. Thus, high school valedictorians have been forbidden to insert even brief religious references in their graduation remarks, despite the fact that they are not authority figures and are platformed along with many other speakers.

In one particularly ludicrous 1996 incident in New Jersey, a first-grader named Zachary Hood was barred from participating in a classroom exercise in which each student read to the class a short text of his or her choosing because the text he had chosen came from a children’s book of Bible stories (an account of the reunion of estranged brothers Jacob and Esau which made no mention of God or miracles). The federal courts at the time sided with the school district, ruling that to allow Zachary to read the story out loud in front of the class would amount to an impermissible endorsement of the Bible by the public school. However, Zachary and his mother won a settlement in a related case in which a drawing he made was removed from a display of the students’ Thanksgiving art because it was religiously themed. As the Becket Fund, which litigated on Zachary’s behalf, notes on its website, the case resulted in a Department of Education guidance in 2003 stating that “students may express their beliefs about religion in homework, artwork, and other written and oral assignments free from discrimination based on the religious content of their submissions.”

Overzealousness in the cause of church/state separation inevitably came into conflict with religious freedom and freedom of expression. The drift away from strict separationism, under which religion and religious speech must be excluded from the government-run spaces, and toward a very different form of neutrality that requires equal treatment for religious and non-religious expression long predates the current moment. Writing in the New York Times Magazine back in January 2000, legal analyst Jeffrey Rosen linked this development not to conservative legal efforts but to the rise of identity politics: “In an era when religious identity now competes with race, sex and ethnicity as a central aspect of how Americans define themselves, it seems like discrimination—the only unforgivable sin in a multicultural age—to forbid people to express their religious beliefs in an increasingly fractured public sphere.” In that sense, Kennedy v. Bremerton continues a longstanding trend.

It also exemplifies the trend of religion as identity politics—specifically, in the context of right-wing culture wars. One may debate whether Kennedy’s public battle against the school district amounted to a spirited defense of his First Amendment rights or to true-believer militancy and attention-seeking, but justified or not, the record leaves little doubt that this battle triggered some ugly and disturbing behavior. School officials received a barrage of verbal abuse and even threats. The head coach, Nathan Gillam, testified that “an adult who [he] had never seen before came up to [his] face and cursed [him] in a vile manner”; Gillam later decided to resign after 11 years on the job out of concerns for his and his players’ personal safety. Even if progressive overreach helped fuel these conflicts, there is no question that right-wing demagoguery played a big part as well.

Does Kennedy v. Bremerton take us into new territory when it comes to potential religious coercion in schools? Interestingly, Millhiser and Volokh, who assess the case very differently, agree on one thing: that its impact as precedent is uncertain because the majority opinion relies on the least controversial (from a First Amendment perspective) version of the facts.

That said, it seems all but certain that the ruling will open the door to other lawsuits from teachers and other public employees who will want to challenge whether prayer or other kinds of speech are protected, and in turn from students who might feel more clearly coerced by an authority figure than did the students in this case. The coming years may bring many more opportunities to see to what extent the current Court’s conservative majority has a genuine interest in protecting religious liberty.