The Boy Genius Who Killed 14 Million Poor People

What is the moral weight of responsibility for the men who carried out DOGE’s work?

1. Booksmart

On The Next Level yesterday Sarah, Tim, and I talked about this monster Bloomberg profile of Luke Farritor. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

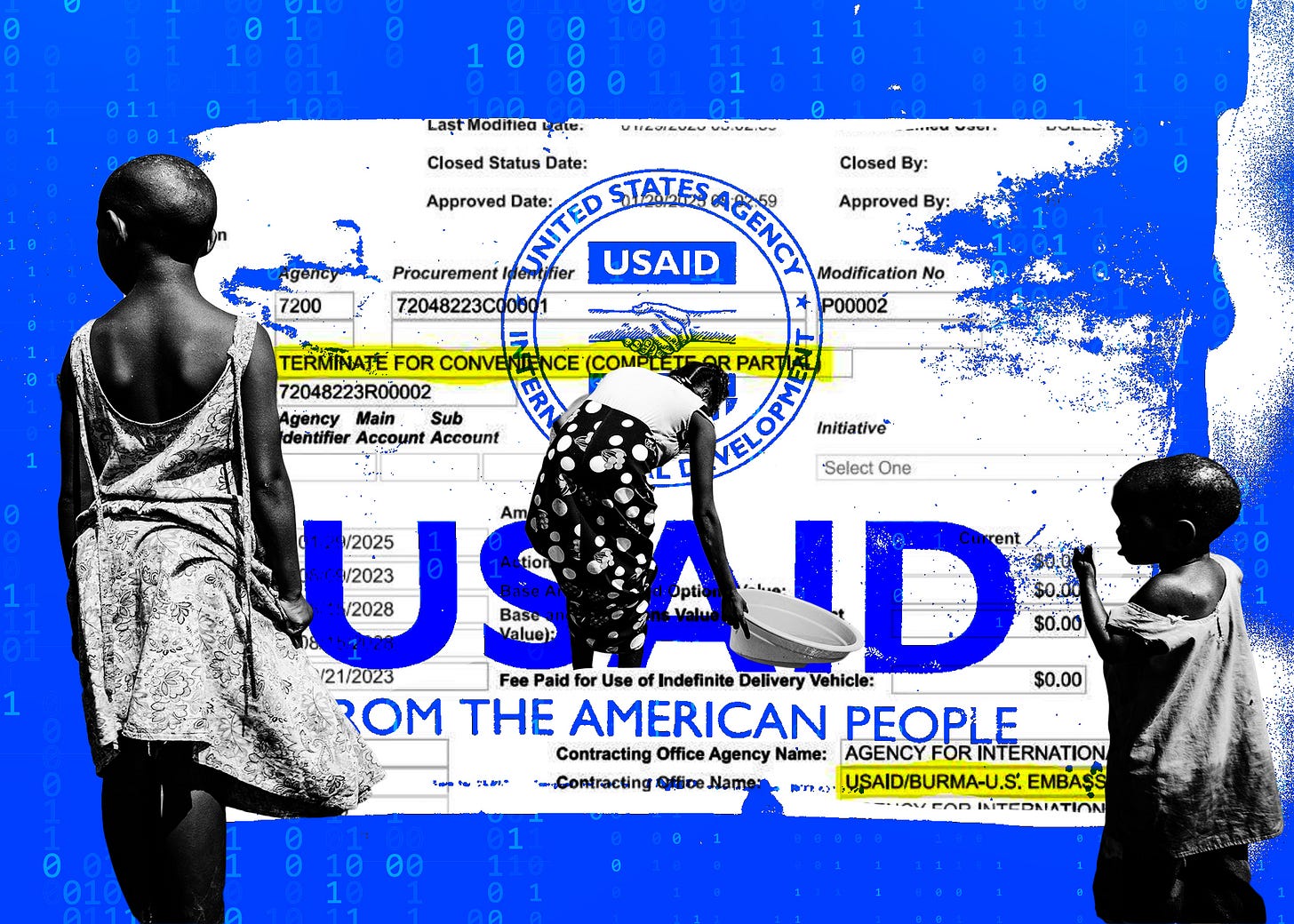

You probably have not heard Farritor’s name before. He is one of Elon Musk’s 23-year-old DOGE bros who helped dismantle key parts of the federal government, including USAID.

The particulars of Farritor’s story are idiosyncratic—he is in almost every way an outlier. Yet the moral component is universal because it presents a simple question: What is the nature of accountability?

Luke Farritor grew up in Nebraska and what struck me most reading the account of his life is the extent of his privilege.

His father is a university professor. His mother is a physician. Farritor seems to have been a child prodigy whose talents were recognized, encouraged, and incubated almost from the moment he hit puberty. He was supported by both his well-to-do family, his community, and a number of institutions that exist to identify and elevate gifted children.

In other words: Farritor’s story is not one of a misunderstood genius who had to fight through an uncaring system. Quite the opposite.

Farritor was homeschooled and by age 15 he was lauded for the art installations he created. He was recruited into the University of Nebraska’s celebrated Raikes School, which is the engineering equivalent of being given a golden ticket. He got an internship at SpaceX and a $100,000 fellowship from Peter Thiel. He won part of the Vesuvius Prize for contributing to the team that decoded a burnt, ancient scroll using AI routines. According the Bloomberg, he had job offers from more or less all of Silicon Valley by the age of 21.

So like I said: privilege. This is a kid who worked hard, but never had to hustle. Who was never told “no.” Even in settings where authority figures expected certain things from him, Farritor was allowed to go his own way:

“School was never a priority for Luke, and that was well understood,” one classmate says. Unlike them, Farritor challenged professors about assignments and skipped classes (to work on the music project, to work on the scrolls). “It’s what kind of set him apart, because he would just grind on side projects and learn,” says another classmate. . . .

Farritor didn’t always invest himself in group projects, some classmates say. Raikes is supposed to be all about collaboration. The program culminates in a project meant to solve a real problem for a company or organization. In November of his senior year, Farritor told his group that he would likely drop out before theirs was complete, according to one of them.

I want to be clear here: I think it’s good that Farritor was allowed to follow his own path rather than have professors hold him to a rigid program. But the point is that this was privilege stacked on top of privilege. It wasn’t like Real Genius where Farritor had to fight his way past blinkered professors. Even in the rarefied air of an elite, publicly-funded school, Farritor was encouraged to march to his own drummer.

In a certain way, when you look at Luke Farritor’s life you’d say: The system worked. This is everything we hope that our society will do for gifted kids. In a world where we often lament institutional failures in education, Luke Farritor got the best of everything.

And then he decided to burn it all to the ground. Because in December 2024 he joined DOGE.