‘The Great Task Remaining Before Us’: Lincoln’s Vision at Gettysburg

On the anniversary of his address, a reminder that democracy requires dedication.

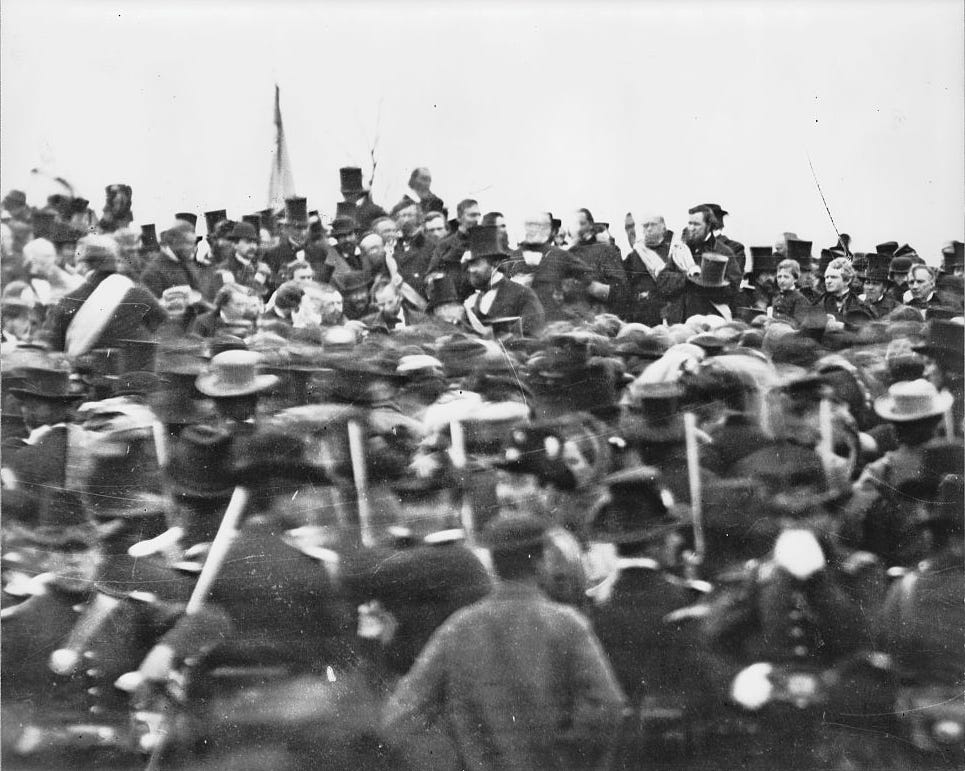

ON NOVEMBER 19, 1863—162 years ago today—the little town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, filled with soldiers, dignitaries, and townsfolk. Scars of the intense fighting of four months earlier, one of the bloodiest battles ever on American soil, were everywhere: barns riddled with damage from cannonballs, trees stripped bare, hastily dug graves marking where regiments had fallen. Cadavers of some rebel troops could still be seen rotting in the sun. The smell of decay was everywhere.

Months earlier, Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania and a committee of state officials had concluded that a national military burial ground, placed next to the graveyard that overlooked the town on Cemetery Hill, was needed. It would honor the Union dead but as importantly restore some measure of dignity to the local farmers’ fields that had become a landscape of horror.

The idea was noble, but the execution was hurried. The politicians had wanted to dedicate the cemetery in October, but the chosen orator, Edward Everett—a former secretary of state, governor of Massachusetts, U.S. senator, and president of Harvard—was unavailable. The distinguished-looking 69-year-old was considered the finest public speaker in the country, a man of enormous erudition and polished delivery; the elected officials of Pennsylvania were more than willing to accommodate his schedule, and so postponed the dedication a month.

Invitations were sent to governors, generals, and public officials. As an afterthought, President Abraham Lincoln was also asked to participate and was politely requested to deliver “a few appropriate remarks.” Lincoln was the one who would follow the main act.

The morning of November 19 dawned crisp and bright. Crowds gathered along the newly graded road, carriages clogging the narrow streets of Gettysburg. Bands played patriotic airs as the procession slowly made its way to the speakers’ platform.

When Everett took the podium, he spoke for two hours from a memorized speech, describing the history of the republic, the causes of the war, and the heroism of the fallen. It was a learned, elegant address—meticulously constructed, intellectually rigorous, and entirely in keeping with the conventions of nineteenth-century public rhetoric. The audience was enthralled, and at the end, they applauded energetically.

Then Lincoln stood. The rangy 54-year-old loomed above the dignitaries seated on the platform. His voice was pitched higher than the audience expected as, reading from a single sheet of paper, he spoke for barely two minutes—272 words in all. Some listeners were startled; a newspaper reporter later wrote that Lincoln’s speech “passed unnoticed by many”; another noted that its brevity was “a disappointment.”

But Everett, the featured orator, understood. The next day, he wrote to Lincoln: “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

It’s easy, from hindsight, to treat the Gettysburg Address just as one of our nation’s greatest speeches, a long-ago eulogy years for a war whose outcome we take for granted. But in November 1863, the outcome of the Civil War was anything but certain. Union forces would still suffer staggering losses for more than another year. The Confederate Army had returned from Pennsylvania and regained strong defensive lines in the South. Anti-war sentiment was still growing in the North, and Lincoln’s own political prospects were uncertain heading into the election year of 1864. Chaos remained for many months after the dedication ceremony at Gettysburg. The nation, in truth, still hung by a thread.

Imagine the mood of the country that autumn. The casualty lists in Northern newspapers filled entire columns. Families across the nation grieved sons and fathers buried in places they would never see. The political debate was bitter and relentless. The press accused Lincoln of incompetence, even madness. Everywhere, people felt the nation’s center was giving way. The republic, it seemed, might not survive.

And yet Lincoln spoke as if it would—as if its survival were not just possible, but necessary, and a part of our civic responsibility.

The Declaration of Independence, to which Lincoln pointed in his opening line, had promised equality but had not delivered it. Lincoln’s genius was to reinterpret that document through the lens of the war’s suffering. In doing so, Lincoln took the present carnage honored at Gettysburg and used it to provide moral clarity for the future. In a time when the Union was far from saved, he dared to describe not what America had been or was, but what America ought to become based on the original promise.

In that brief speech which illuminated a moment of both exhaustion and despair, Lincoln spoke not of the dead, nor even of victory. He spoke of purpose. He invited the country to see beyond the chaos—to glimpse the unfinished work of democracy itself. And then he asked his listeners to resolve that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom.”

That was the genius of the Gettysburg Address that should still speak to us today, that should still speak to us in all the days of our democracy. It was not a declaration of victory or even a statement of confidence; it was an act of faith. Faith in the principle that a government of the people, by the people, for the people could endure even after chaos, division, and unspeakable loss.

Lincoln’s words reframed despair into determination. They told Americans that meaning could be forged from suffering. That unity was possible through shared purpose.

THERE’S ANOTHER SUBTLE FEATURE of the address that still deserves attention. As a smart Marine once told me, pay attention to Lincoln’s insistent use of the plural.

He did not say I or me. He said we, us, and our.

“We are engaged in a great civil war. . .”

“We are met on a great battle-field of that war. . .”

“We are met to dedicate a portion of it. . .”

“It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. . .”

“It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here. . .”

“. . . that we here highly resolve. . .”

Amid the most divisive period in American history, Lincoln’s pronouns were unifying. He refused to divide his listeners into North and South, Union and rebel, righteous and wrong. He spoke to America itself—to a desire for shared identity beyond politics, geography, or ideology.

He offered not blame, but belonging.

And that linguistic choice still provides something extremely profound. Great leaders do not shrink the circle of citizenship; they widen it. They remind us that the first word of our Constitution—We—is both promise and responsibility.

Today, eight score and two years after Lincoln’s speech, we hear predictions of national unraveling, the fear of another civil conflict—political, cultural, or even physical. We hear voices insisting that the “real America” belongs to one side or another, that compromise is weakness, that empathy is naïve.

It shouldn’t be overstated, but it’s true that the mood of November 2025 has echoes of November 1863 when Lincoln spoke: anxiety about the future, anger over leadership, distrust in institutions, and a creeping sense that we are two nations sharing the same land.

But Lincoln’s message at Gettysburg remains a counterweight to despair. Democracy isn’t maintained by perfection; it is renewed by participation. Our republic survives not because of certainty, but because of faith: faith in each other, and in the unfinished work of freedom.

When Lincoln spoke he had no guarantee that the Union would prevail, no promise that slavery would end, no assurance that he himself would live to see peace. Yet he still called Americans to imagine a better future—one founded on equality, liberty, and especially shared responsibility.

If he could speak of a “new birth of freedom” amid such darkness, surely, we can speak of national renewal today—not as nostalgia, but as obligation, a shared purpose toward which we can work.

A few weeks ago, I was with some friends at the place where Lincoln gave his address. That portion of the cemetery, where Lincoln spoke, remains one of the quietest places in America. The wind moves across the ridge, brushing the flags and passing across the graves. And if you stand there long enough, you can almost hear his words carried back through time—not as history, but as instruction.

“It is for us the living. . .”