1. Labor Day

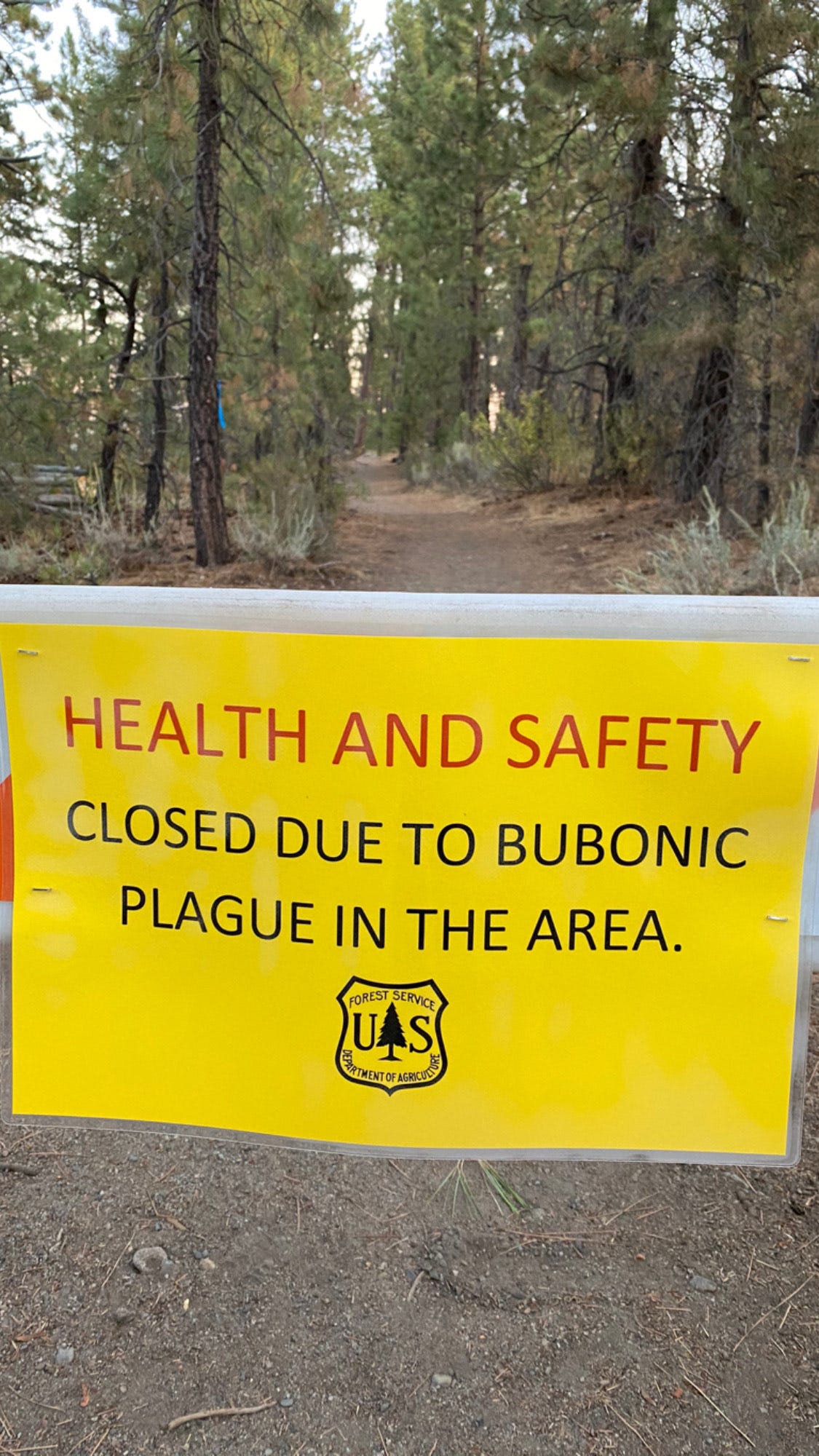

Before we get started, I'd like to share a photo sent to me by one of my buddies. I assure you that this is a real thing and was not photoshopped:

Maybe this is peak 2020?

Because we've got an outbreak of THE BUBONIC FORKING PLAGUE to go along with everything else.

Good times. Now let's move on.

We are now past another of the big campaign milestones: Labor Day.

How does the race look?

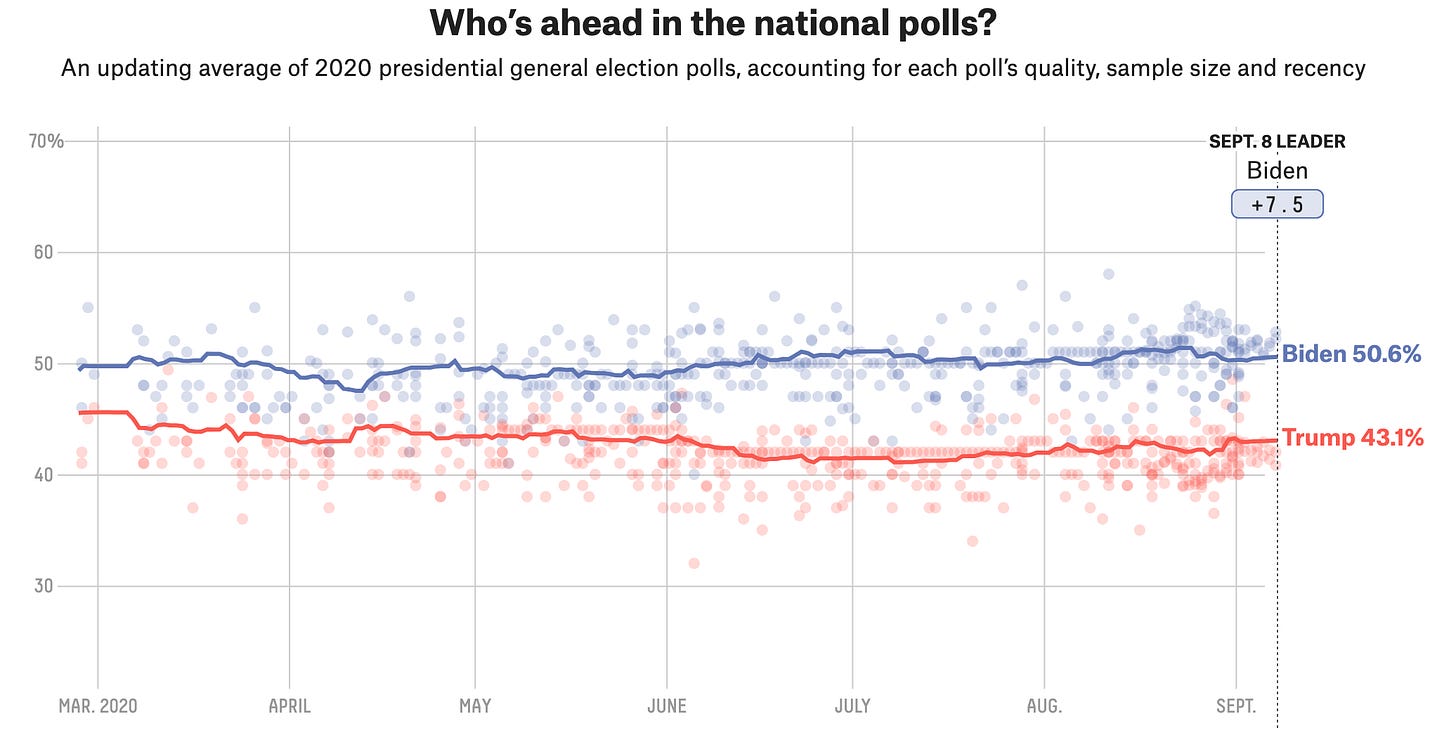

Pretty much like it's looked the entire way:

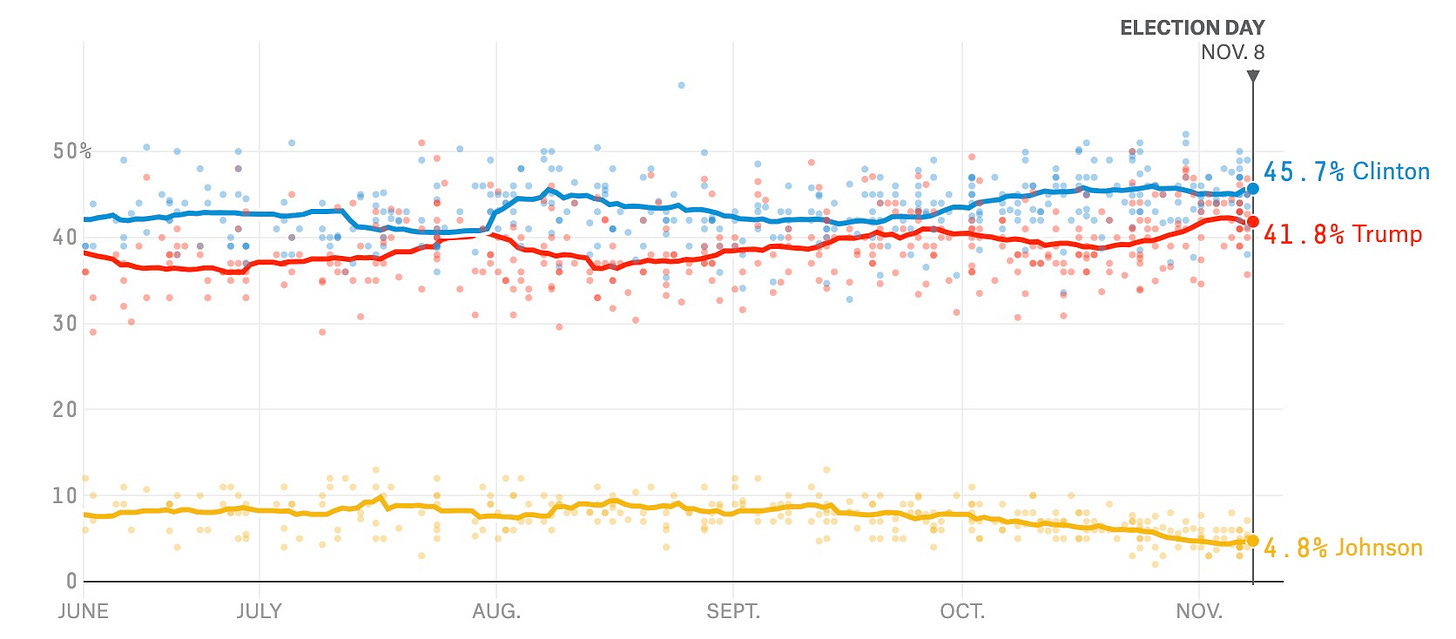

Let's see how this compares to the polling in 2016:

A few points to note:

On September 8, 2016, Hillary Clinton was +3.3

Today, Biden is +7.5, so his lead is more than double what Clinton's was at this point.

Relative to 2020, the 2016 race was more volatile. There were moments when Clinton and Trump were tied; moments when Trump was in the lead; moments when Clinton's lead was large (+8), and moments when Clinton's lead was within the margin of error.

To date, Trump has never been closer than -3.4 against Biden.

On September 10, Biden will have been over the 50 percent mark for a full month. Clinton was never over 50 percent, or even very close to it.

Now, what does that all mean?

It means this: If the election were held under normal circumstances then the most likely outcome would be a Biden victory of somewhere between +5 and +7 in the popular vote.

What's more, the confidence level on that likelihood would be as high (or higher) than it's been at this point in any recent election.

But there are two problems:

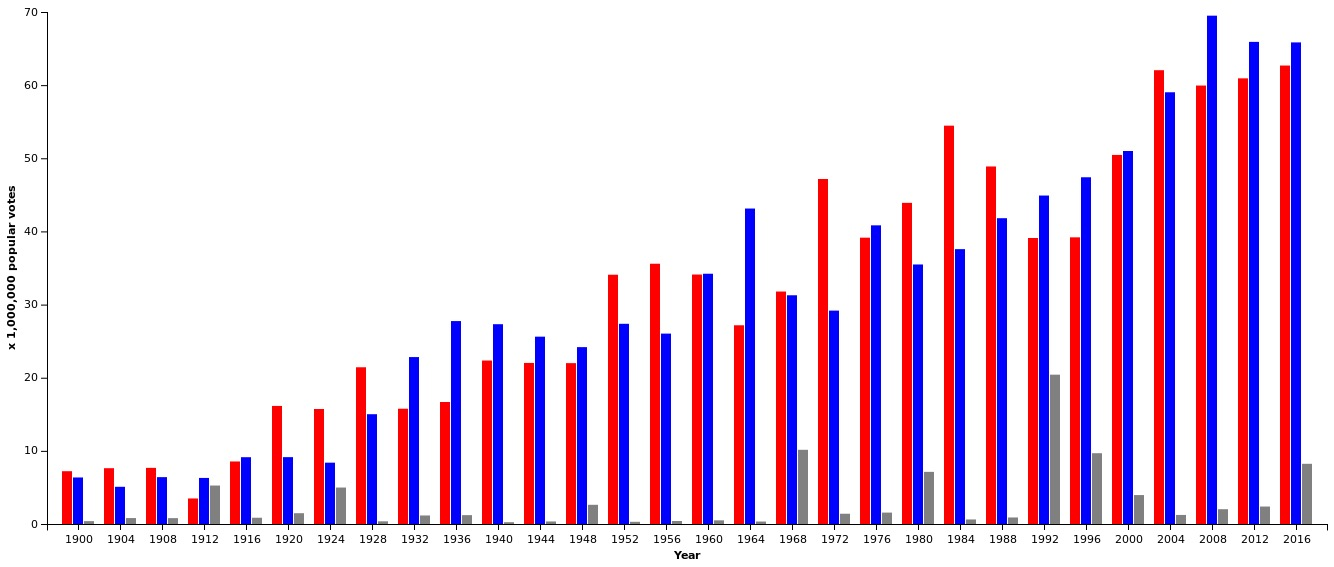

(1) The election will not be held under normal circumstances. I cannot emphasize this enough: It is almost impossible to make useful assumptions about what the pandemic will do to voting. Here is a chart showing the raw number of total votes in presidential elections dating back to 1900.

Any model of the eventual outcome relies on having an educated guess on the range of total votes to be cast. Post 9/11, our election turnout have ranged from 121 million to 130 million votes.

In the pandemic environment do you think the total turnout is likely to be closer to 100 million? Or 140 million?

Nobody knows.

And if you can't even get a baseline on raw vote totals, then everything else in a model is going to be a crapshoot.

(2) The Electoral College advantage for Republicans has grown to such a degree that even a +5 popular vote margin for John Biden leaves Trump with a 10 percent chance of victory in the EC.

All of which is to say that we are in a paradox. We know what the mood of the country is. We know what people think.

But we have no idea who will be elected president 55 days from now.

2. Movie Theaters

I went to the movies last night for the first time in half a year.

What I saw was not encouraging for the future of the industry.

First the good news.

I went to an AMC where they dispensed with security theater (no temperature check). They also drew a hard line on masks at the front door, insisting that bandanas and neck gaiters were not sufficient.

There ends the good news.

Here is the bad news:

Of the 9 people at my screening, only three of us wore masks. The other 6 were eating popcorn and so did not wear their masks at any point during the presentation of the film.

What good is it to have a "wear a mask" policy if there's a loophole that says, "If you buy a bag of popcorn, you don't actually have to wear your mask"?

I put this under the "bad news" category because people are not going to come back to theaters en mass if mask protocols aren't working.

But here's what I found really depressing: AMC is the best large chain in the country. And it seems like the company's response to an extinction-level event is not to innovate their way out of the problem, but to cross their fingers and hope that everything goes back to normal somehow.

Let's start with safety protocols.

I'm not a mask absolutist. There are plenty of situations in which mask usage is superfluous. But sitting in a theater for 150 minutes is not one of them. If you were going to rank activities by their potential to spread the virus, theatergoing would be in the first, riskiest tranche.

So first, the movie theaters ought to be providing an N95 (or KN95) mask to everyone who enters as part of the ticket price.

Second, they ought to close the concessions. You can't leave a loophole that big in your mask policy and expect to get your audience back. Would losing concessions revenue be death for theater chains? Yes. But you have to understand that they're already dead. You bring back concessions after there's a vaccine.

Next there's the business itself. The single most depressing thing I saw last night was an advertisement during the pre-roll for the AMC A-List program.

Let me explain.

Back in the beforetimes, there was a tech company called Moviepass that was basically a scam. You paid them a monthly fee and you got tickets to as many movies as you wanted.

AMC decided to launch their own version. They called it AMC A-List. And the idea was, you pay them $20 a month and can see up to three movies a week at their theaters. It was their biggest initiative. They pushed in relentlessly, to only modest success.

And here they were—mid-pandemic—still pushing audience members to subscribe to A-List.

Do you think there is anyone in America right now who would go to three movies a week?

I do not.

So with the theatrical window closing and the streaming services attempting to kill the movie theater, AMC is pushing the same zombie program they were pushing before COVID.

That's not how you save a dying business.

3. Jobs

An old rant from David Graeber about TPS reports and all the rest:

In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century's end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a 15-hour work week. There's every reason to believe he was right. In technological terms, we are quite capable of this. And yet it didn't happen. Instead, technology has been marshaled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless. Huge swathes of people, in Europe and North America in particular, spend their entire working lives performing tasks they secretly believe do not really need to be performed. The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound. It is a scar across our collective soul. Yet virtually no one talks about it.

Why did Keynes' promised utopia—still being eagerly awaited in the '60s—never materialise? The standard line today is that he didn't figure in the massive increase in consumerism. Given the choice between less hours and more toys and pleasures, we've collectively chosen the latter. This presents a nice morality tale, but even a moment's reflection shows it can't really be true. Yes, we have witnessed the creation of an endless variety of new jobs and industries since the '20s, but very few have anything to do with the production and distribution of sushi, iPhones, or fancy sneakers.

So what are these new jobs, precisely? A recent report comparing employment in the US between 1910 and 2000 gives us a clear picture (and I note, one pretty much exactly echoed in the UK). Over the course of the last century, the number of workers employed as domestic servants, in industry, and in the farm sector has collapsed dramatically. At the same time, ‘professional, managerial, clerical, sales, and service workers’ tripled, growing ‘from one-quarter to three-quarters of total employment.’ In other words, productive jobs have, just as predicted, been largely automated away (even if you count industrial workers globally, including the toiling masses in India and China, such workers are still not nearly so large a percentage of the world population as they used to be.)

But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world's population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning of not even so much of the ‘service’ sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations. And these numbers do not even reflect on all those people whose job is to provide administrative, technical, or security support for these industries, or for that matter the whole host of ancillary industries (dog-washers, all-night pizza delivery) that only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones.

These are what I propose to call ‘bullshit jobs’.