Trump Supporters’ Weak Case Against Kicking Him Off the Ballot

And what the courts will make of the Colorado and Maine rulings.

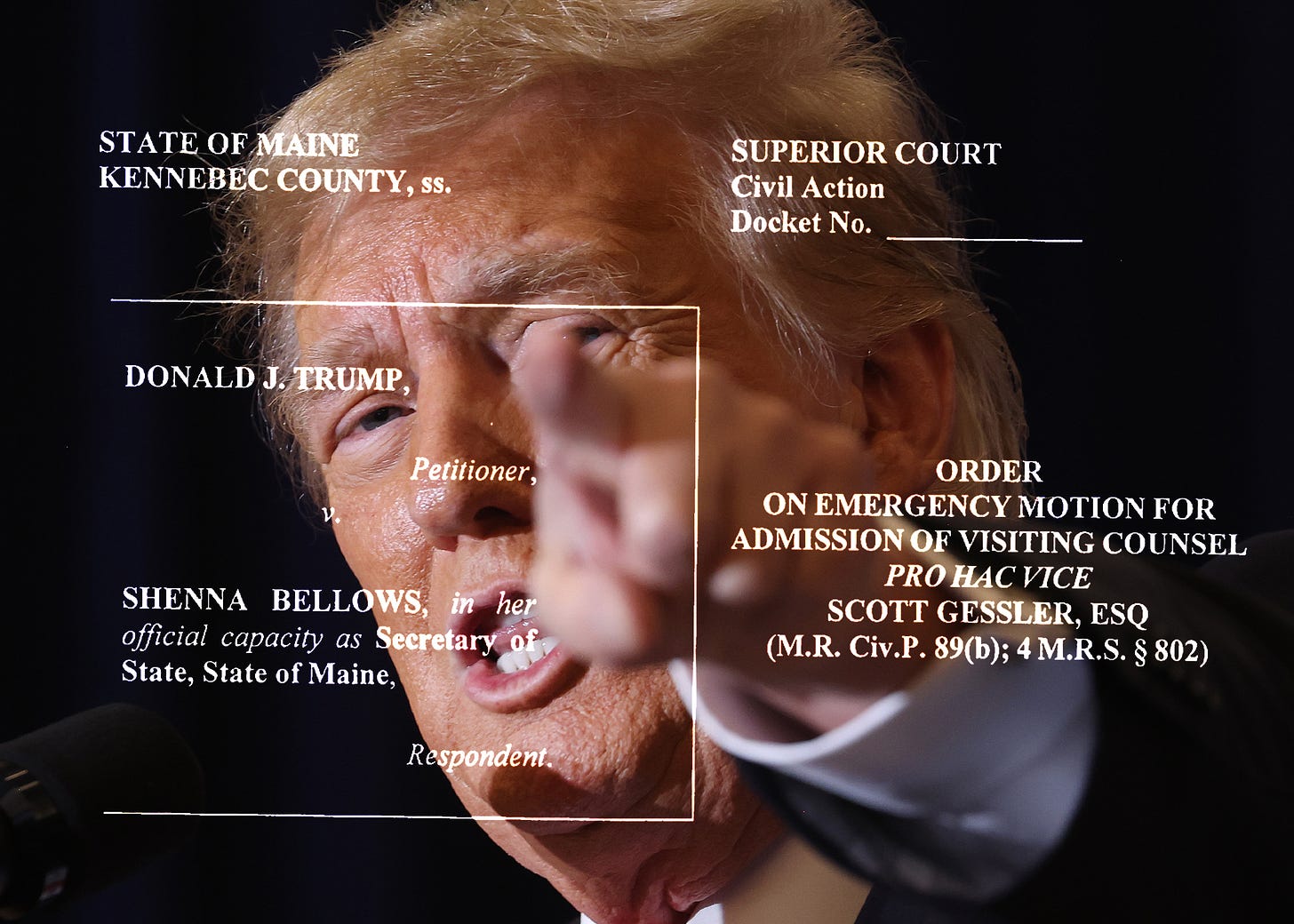

ON TUESDAY, LAWYERS FOR Donald Trump filed a lawsuit in Maine asking that Secretary of State Shenna Bellows’s ruling disqualifying him from the presidential ballot be vacated and that his name be restored to the ballot. Lawyers representing both Trump and Bellows have asked the court to hear the case on an expedited basis.

Bellows’s December 28 ruling booting the former president from the ballot in Maine came nine days after Colorado did the same thing. In both cases, the decision was made on the grounds that Trump engaged in an insurrection after having taken an oath to support the Constitution and is accordingly disqualified under Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The main difference between what each state has done is that in Colorado the decision came from the Colorado Supreme Court while in Maine the decision was issued by the secretary of state, who is appointed by the state legislature.

As Charlie Sykes noted yesterday, some commentators have rushed to declare both rulings anti-democratic, as if voters have a “democratic” right to pick whomever they want for president under our system of laws. They don’t: Not only does the Constitution impose age and residency requirements (among others) for anyone seeking the presidency, but each state has its own laws governing ballot eligibility, including feats like securing a minimum number of signatures from registered party members, filing fees, and deadlines. If a Republican nominee for president in California fails to secure the signatures of 1 percent of that state’s registered party members—over 52,000 people—by December 15, for example, that candidate is banned from the presidential ballot. Nobody is howling that it’s somehow anti-democratic to impose such hurdles. This complaint only seems to arise when the candidate is Trump.

Critics of the two rulings cite due process and the lack of a criminal jury verdict—but as I noted yesterday, as a legal matter, these critiques are deeply flawed. In the Colorado case, Trump actually got due process via a multi-day evidentiary hearing—even though the protection of due process only dubiously applies to presidential runs in the first place.

The critiques of Maine Secretary of State Shenna Bellows are even more intense than the criticism of the Colorado ruling, since the secretary of state isn’t a court—but they are legally way off, as well.

Each state has its own process for deciding who is qualified for the presidential ballot. In Maine, that process begins when a candidate files a primary petition and a registered voter challenges it. Under Maine law, it’s the secretary of state who is tasked with reviewing the challenge at a hearing. The petitioner—here, Donald Trump—gets to present evidence and defend the legitimacy of his primary petition. That happened in this case. Three voters challenged his eligibility, Trump’s lawyers presented his case in response, and, following a hearing on December 15, Bellows issued her decision pursuant to her statutory authority.

Under the same law, the decision is reviewable in the Maine Superior Court. On Tuesday, Trump filed his appeal pursuant to that law. That is due process at work. The Superior Court’s decision can be appealed to that state’s higher court, and then to the highest court in that state, and then to the U.S. Supreme Court. Again, ample due process for Donald Trump.

CRITICS CONTEND FURTHER that Bellows is unqualified to decide if Trump engaged in an insurrection or rebellion in the first place. She’s not a lawyer; she’s an executive branch official who undoubtedly relied on seasoned state counsel in making her decision. And her 34-page ruling reflects lawyerly expertise. It is well reasoned, cites the appropriate law, reviews the evidence in the record, and is, accordingly, well positioned for a court’s review.

Now for a few points about the substance of her decision.

Under Maine law, the secretary of state is responsible for preparing ballots for a presidential primary, and must “determine if a petition meets the requirements” of Maine law. Those requirements include a set number of voter signatures and other things, including a written statement under oath from the candidate that he “meets the qualifications of the office the candidate seeks.” Nobody disputes that those qualifications include the criteria for eligibility laid out in the U.S. Constitution, or that Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment is part of the Constitution.

In short, Bellows executed her obligation to ensure that the state’s requirements for getting on the ballot are satisfied. If a “teenager” tried to run, she notes, she’d go through the identical process, presumably without the cries of outrage that Trump evokes from people across the political spectrum. President Joe Biden won’t be on the New Hampshire primary ballot either, over a dispute within the Democratic party regarding whether New Hampshire’s or South Carolina’s primary will lead this year. No abounding indignation on that one. Crickets.

As for whether January 6th was an insurrection, and whether Trump engaged in it, the secretary of state observes that “the parties do not meaningfully dispute the events of January 6, 2021.” Hear that again: Trump’s lawyers have not disputed what happened on January 6th. The point of a trial—which critics claim he’s constitutionally entitled to before being kept off any ballot across the country—is to resolve factual disputes. Here, Bellows reminds us:

Multiple government reports . . . entered into evidence confirm that a large group of people violently attacked the Capitol with the intent of preventing the certification of the presidential election. This resulted in a lockdown of the Capitol complex, an evacuation of the Vice President and congressional leaders, an interruption of official House and Senate proceedings, and multiple deaths and injuries.

She goes on to summarize Trump’s involvement, which she defines to include incitement of insurrection, and calls it “a compelling narrative, the facts of which are not in serious dispute.” Bellows also rejects Trump’s word-salad alternative definition for insurrection: something that’s “violent enough, potent enough, long enough, and organized enough to be considered a significant step on the way to rebellion.” This is not a definition, let alone a legally workable one. The Maine courts will undoubtedly agree.

Despite all this, the attacks on these state officials’ decisions to invoke state law in response to the insurrection continue, and have reached an ugly level: Bellows’s home address and cell phone were posted online, she received death threats, and was the victim of a ‘swatting’ incident (where a phony 911 call was placed to her home). A terrible foretaste of the lawlessness we might see in the months ahead, as Donald Trump’s supporters act in service of his lies and ambition.