We Need a New Great Awakening

This dire moment in our nation’s moral life cries out for a renewal of hearts.

THE TURN TOWARD THE HOLIDAYS feels more difficult this year. All around us we’re confronted with tragedies deeply at odds with the spirit of the season: a college student on her way home to surprise her parents deported instead by our government to a country she left when she was 7; students forced to cower in fear under the desks on which they should be taking their final exams; a head of state responding with mockery and derision to the brutal murder of a loving couple.

It feels as if we are in a moment in which the moral ground beneath us is shifting. Compassion is in retreat and hatred is on the rise. Alienation is ascendant and community harder to find. Our public life is fractured, our discourse coarsened, and our confidence in one another eroded. Unmoored and anxious, the temptation for many is to retreat into tribes or despair. Or both.

Yet history whispers that such times are not only moments of danger. They are also invitations.

America has been here before.

Again and again, when the nation has faced spiritual exhaustion or moral confusion, waves of renewal have risen—not imposed from above, but kindled in hearts, congregations, and communities. We have called these movements “Great Awakenings,” moments in which we collectively re-find our purpose, conscience, and responsibility to one another in response to a feeling of having lost those things.

The First Great Awakening of the 1730s and 1740s emerged in a colonial society marked by social fragmentation, growing distrust in institutions, and widening inequality. By transcending denominational boundaries, it helped unite diverse populations across the colonies, creating a national spirit that would prove essential to the revolutionary cause. By emphasizing new forms of religious authority and community, it channeled the distrust of old institutions into a project of construction rather than destruction. And its focus on the dignity of the individual planted the seeds from which the Founders’ democratic imagination could grow.

Two generations later, the Second Great Awakening built on this inherited revivalist ethos but unfolded in a far more unsettled republic. Rapid market expansion, territorial growth, and the disintegration of older communal bonds again produced moral anxiety and institutional strain. Revivalists responded by radicalizing the logic of the first awakening: Faith was not only personal but activist, demanding the reform of society itself. New evangelical networks transformed conscience into action, giving rise to abolitionism, women’s moral authority, and educational reform.

The Third Great Awakening, stretching into the early twentieth century, responded to the transformations of industrialization, urban poverty, and immigration. The Social Gospel movement urged Americans to see structural injustice as a moral concern. It helped inspire labor reforms, settlement houses, and a broader sense of social responsibility. Once more, spiritual renewal and civic renewal moved together, braided strands in a single cord.

These awakenings were imperfect. They were marked by contradictions, blind spots, and exclusions that still wound us. Yet they shared a pattern of renewal out of periods of moral dislocation, and therefore a common conviction: that democracy cannot survive on procedures alone. It requires character. It requires the cultivation of habits of the heart.

TODAY, WE FIND OURSELVES in another such hour. Our technologies connect us instantly yet estrange us deeply or diminish our dignity. Our politics reward outrage over understanding. Too often, we speak of fellow citizens as enemies rather than neighbors. Trust—so fragile, so essential—has been squandered. Many Americans feel that the promise of the nation is slipping beyond reach, while others feel unseen, unheard, or expendable.

This is not merely a political crisis. It is a spiritual one.

Nowhere is this more painfully evident than in how our government treats immigrants in our name.

A nation has the right—and the responsibility—to enforce its laws and manage its borders. Serious people of good faith can disagree about policy, numbers, and systems. But there is a profound moral difference between enforcement and cruelty, between order and degradation. We have crossed that line too often, and the cost is measured in human suffering.

Consider the child who is forced to watch in terror as their parent is ripped from their car and whisked away by masked agents.

Consider the father who died alone in government custody after pleading for medical help that came too late—or not at all.

Consider families packed into overcrowded facilities, sleeping on concrete floors under foil blankets, their dignity stripped along with their freedom.

These are not abstractions. They are mothers and sons, teenagers and grandparents, people made in the image of God, whatever name we give that sacred truth.

We are told, sometimes, that such suffering is regrettable but necessary—that harshness deters, that cruelty is a tool of policy. History teaches otherwise. Cruelty corrodes the one who wields it. It deforms institutions and deadens consciences. And it leaves a residue on the moral character of a people who look away.

Counter to any notion we are offered that our religion somehow requires this, across our faith traditions, the actual command is unmistakable. “Do not oppress the stranger,” the Hebrew scriptures repeat, “for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” Jesus identifies himself with the hungry, the imprisoned, the foreigner: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.” Islamic teaching holds that saving one life is as if saving all of humanity. Hospitality to the vulnerable is not an optional virtue; it is a test of who we are.

When we normalize the humiliation of the powerless, something in us breaks. When suffering becomes bureaucratic routine, our moral imagination shrinks. And when that happens, democracy itself is imperiled—because a society willing to deny the humanity of some will eventually rationalize denying the rights of many.

This is why if we are to survive this moment, let alone rise from it, we must do more than reform our politics, we must call forth a new Great Awakening.

Such an awakening would not ask us to agree on every doctrine or policy. It would ask something at once both simpler and harder: that we recover a shared moral horizon. That we remember democracy is not only a system of government but a practice of mutual regard. That decency is not weakness, and inclusion is not a threat. That freedom untethered from responsibility corrodes the soul of a people.

A moral reawakening would compel us to look honestly at what we are doing to immigrants—and why. It would demand laws enforced with humanity and policies shaped by the recognition that every person has inherent worth. It would move us from indifference to accountability, from fear to courage.

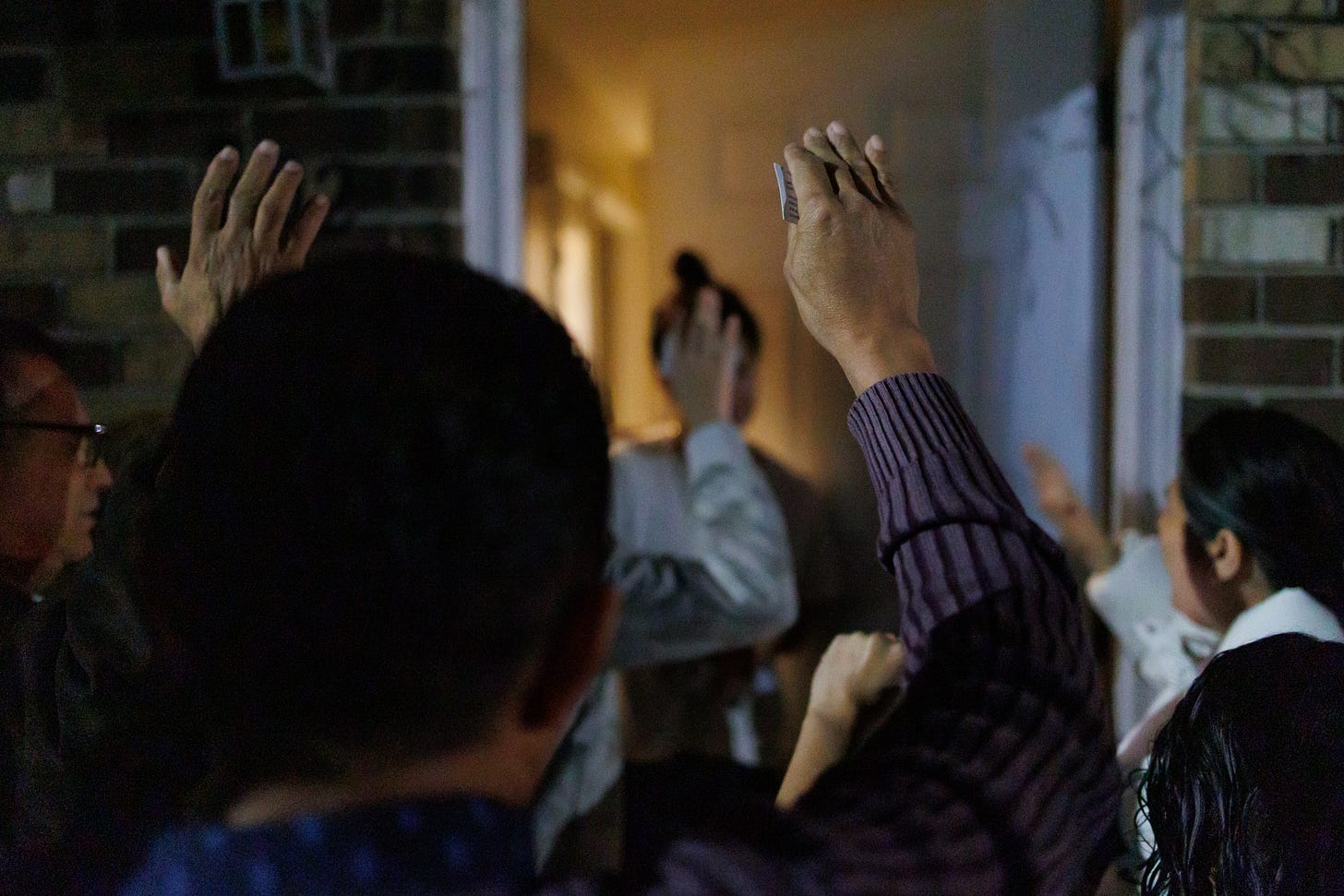

Such an awakening would begin from thousands of different origin points. It would begin with individuals choosing compassion over cruelty, truth over convenience, humility over performative certainty. It would be visible in congregations opening their doors wider, in schools teaching not only skills but character, in families recommitting to listening across difference. It would take shape in civic spaces where disagreement is real but dehumanization is refused.

To make our own small contribution, the organizations we lead have launched a new effort intended to remind us that people of diverse faiths and beliefs in this country reject the terror and cruelty that our government’s current approach to immigration is imposing on our friends and neighbors.

The campaign includes an ad from Interfaith Alliance and Protect Democracy, running nationwide this holiday season, with a clear message: In America, we love our neighbors. The ad contrasts the brutality and abuses of ICE—mass deportations, children separated from their parents, protesters harassed, sanctuary spaces invaded—with the warmth, compassion and hospitality of the holiday season. It aims to mobilize religious Americans and all Americans to demand that ICE and DHS stop attacking our neighbors, and calls upon our political and religious leaders to stand in solidarity against their cruelty.

EVERY GREAT AWAKENING in American history arose not because conditions were ideal, but because they were intolerable. People sensed that the old ways were failing, and they dared to believe that renewal was possible.

We dare, too.

The task before us is not to win arguments, but to begin to heal a moral ecology. To cultivate the virtues without which no free society can endure: honesty, courage, patience, generosity, empathy, and hope. Hope, especially—not as naïve optimism, but as disciplined commitment to the common good.

In troubled times, the question is not whether history will judge us. It will. The question is whether we will rise to the moment we have been given.

May we have the courage to awaken again.

Paul Brandeis Raushenbush, an ordained Baptist minister, is the president and CEO of Interfaith Alliance and host of the podcast The State of Belief.

Ian Bassin is the executive director of Protect Democracy.