What ‘Regime Change’ in Venezuela Would Really Mean

It’s not clear the administration has settled on a goal, much less considered the consequences.

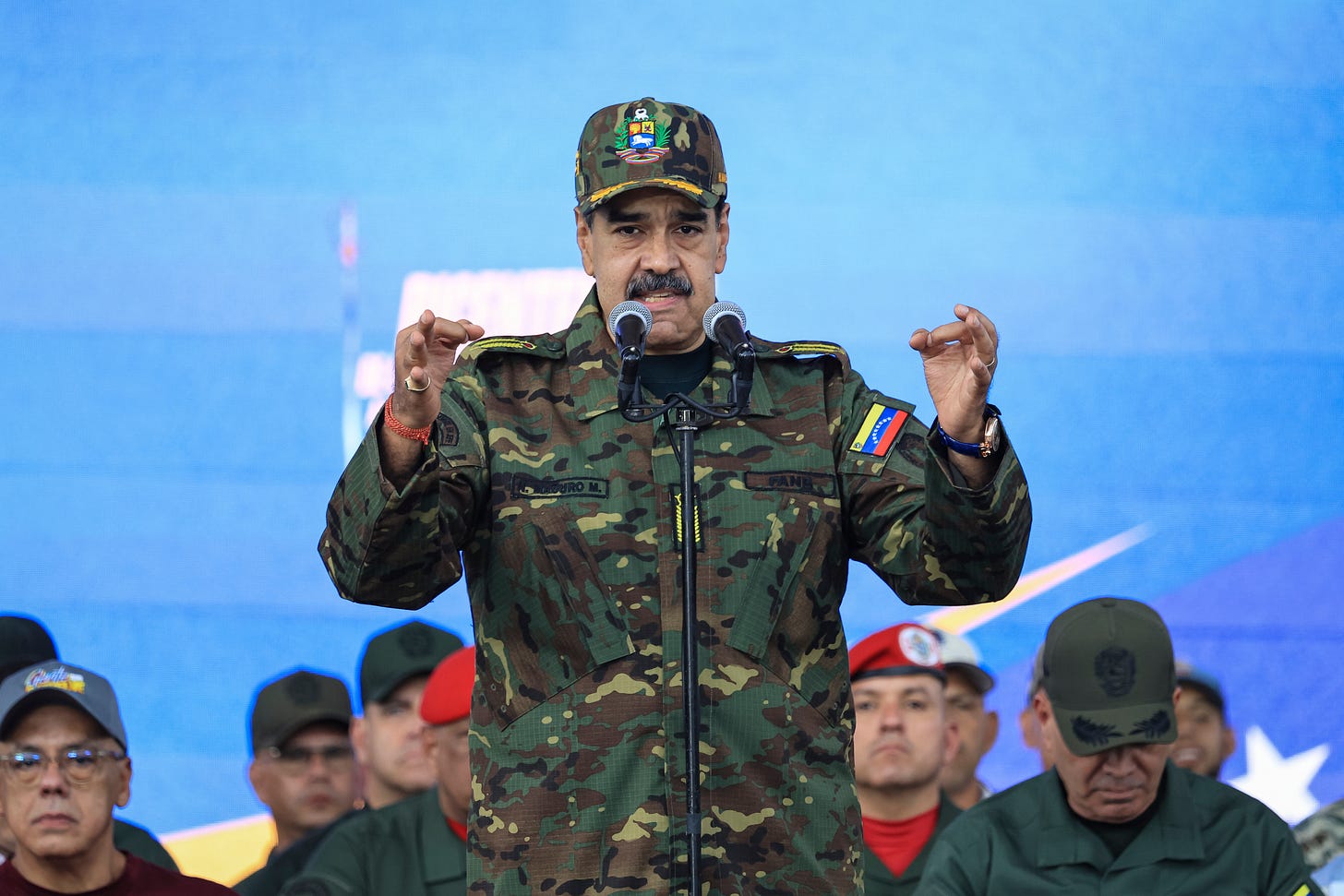

AS THE TRUMP ADMINISTRATION INCREASES military pressure on the Maduro regime in Venezuela, a debate has emerged about whether the administration’s goal is “regime change”—and whether it should be. The term “regime change” is fraught, for good reason. It is associated with America’s long, frustrating wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, but the phrase doesn’t specify the details of a goal or desired end state, much less a plan to get there. From a military perspective, the inherent vagueness of the term is a major problem.

The U.S. military trains for and is prepared to conduct a variety of missions: deterring adversaries, defending allies, attacking an objective or striking a target, enforcing blockades, and providing humanitarian relief, to name a few. These missions are defined in doctrine, authorized by law, resourced through budgets, and trained for over decades.

Regime change is none of those, because it is not a military mission. The military can defend things, attack things, destroy things, and move lots of stuff around the world, but it can’t, by itself, change the political organization of a country.

Regime change is a political act of extraordinary consequence—one of the most complex, costly, and uncertain undertakings a nation can attempt. When the United States treats regime change as a discrete military option rather than a whole-of-government, generational commitment, it repeats mistakes we have made very recently and ignores lessons we have paid dearly in blood, treasure, and reputation to learn.

I know this not just from theory, but from experience.

As a young director on the Joint Staff during the run-up to the 2003 war in Iraq, I remember the internal discussions when “regime change” became the stated objective handed to us by Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld. The phrase was simple; the reality was not. It took sustained persuasion by many senior officers to convince senior civilian leaders that overthrowing a government and being solely responsible for the aftermath was not something the Department of Defense could—or should—own alone.

As events demonstrated, the American military—with the support of our allies and partners—was able to destroy Saddam Hussein’s military and government quickly, just as we and select Afghan partners had toppled the Taliban two years earlier. But it’s one thing to remove a regime; it’s another to replace it.

From a profession-of-arms perspective, replacing a regime requires far more than military excellence. It requires alliance management, post-conflict security and civil affairs forces, economic stabilization, political legitimacy for the new government, planning for thousands of issues the military doesn’t understand, and time measured not in weeks but in years.

Yet the language used in 2002 and 2003 suggested otherwise. To argue that the military could accomplish “regime change,” civilian proponents inside and outside the Pentagon cited precision strikes, large-scale invasions, logistics flows, and covert actions as evidence of our military’s readiness for the mission. These proclamations were all beside the point because those capabilities indicated preparedness for tactical battles and major military operations, not the mission’s political consequences. That distinction—between what is militarily possible and what is politically survivable—had faded from the public discourse. And it is fading again.

One reason regime change is so easily discussed is that it is so rarely defined. Does it mean removing a single leader? Dismantling an entire governing apparatus? Installing a new political order? Each of those implies a radically different level of responsibility, risk, and duration. Removing a leader does not necessarily replace a regime. And even dismantling an entire regime does not, by itself, confer legitimacy on whoever and whatever comes after it.

Who governs the day after the old system collapses? Who provides security when police forces, militaries, and internal security services fracture, disappear, or form an insurgency? Who pays to stabilize the economy, restore basic services, and rebuild institutions when key members of the old regime’s bureaucracy flee? And for how long does the intervening power remain responsible for outcomes it can influence, but not fully control? The United States has repeatedly demonstrated an extraordinary ability to plan for the defeat of enemy forces, but what it has failed to do—and appears to be doing again—is plan with equal seriousness for the political, social, and economic vacuum that will inevitably follow.

Recent reporting makes clear how casually these issues are being treated. On December 27, after more boat strikes and an alleged attack on an “implementation area” for drug traffickers on Venezuelan soil, the New York Times reported that the administration has coalesced around three objectives: limiting Nicolás Maduro’s power, using military force against drug cartels, and securing access to Venezuela’s vast oil reserves. Each of those goals, standing alone, would represent a complex national undertaking. Together, they constitute a sweeping agenda with regional and global implications.

The most revealing of these objectives is the first. “Limiting Maduro’s power” sounds restrained, even cautious. But that goal is vague. As the administration orders American military personnel to extend their tours and place themselves in harm’s way—and as it implicitly asks the American people to support an expensive military buildup in the Caribbean and an armed conflict against Venezuela—it hasn’t yet explained if its goal is to prevent Maduro from causing problems in neighboring countries or in the United States, to try to scare or pressure the people around Maduro into replacing him with someone else, or to topple the authoritarian government of Venezuela outright. This is how nations drift into commitments they have not fully examined—what the military calls “mission creep.” Pressure becomes intervention. Narrow objectives become expansive responsibilities. What began as an option on paper becomes unavoidable once things start blowing up.

THE U.S. MILITARY LEARNED A LOT of important lessons from the Iraq War—ones that our civilian leaders would be well advised to ask about, and our military leaders ought to reinforce with their civilian counterparts.

The first is that military victory does not equal political success. Toppling a regime can be fast; stabilizing a country never is. The most successful cases of American “regime change” took years: The American military occupied part of Germany for four years after the end of World War II. In Japan, the occupation lasted seven years—and American forces remain stationed in both countries to this day.

The second lesson is that dismantling or hollowing out state institutions creates chaos by design. Police and military forces do not simply vanish without consequence. Neither do bureaucracies and economic systems. Left behind are armed men, unpaid officials, and populations desperate for order.

Another lesson is that external actors always rush into the vacuum. Iran, militias, criminal networks, and proxy forces did not wait politely in 2003. Likewise, Venezuela has friends in Cuba, China, Russia, and Iran, and the region is chock full of organized, sophisticated criminal groups, as the administration well knows.

We should have also learned from our time in Iraq that legitimacy cannot be imported. Governments derive legitimacy from their own people, not from foreign flags, friendly ex-pats, or external timetables.

Finally, time horizons stretch. What is brief in planning becomes prolonged in practice. Months turn into years, years turn into decades.

The United States eventually adapted in Iraq, learning painful lessons about counterinsurgency, governance, oil economies, and coalition warfare. But that learning came at enormous cost—in lives, credibility, and strategic position. The tragedy is not that Iraq was hard. The tragedy is that we acted as though it would not be.

If regime change is being seriously considered, we have learned that the military will have to plan for a significant, sustained force presence and a draining long-term internal security mission. The military and our country’s civilian leaders will have to accept that casualties will occur and continue long after any combat operations end.

If regime change is the goal, it cannot be treated as a project for the Defense Department alone, with interagency support added later. Diplomacy must precede intervention, not follow it. Governance planning, political transition frameworks, and coalition maintenance are not after-action tasks. They are prerequisites. Regional dynamics matter deeply. Iraq sat in a tough neighborhood. Venezuela sits among neighbors that are currently friendly to the United States—but history suggests that regional sentiment can shift rapidly when a neighbor’s sovereignty is violated or instability spreads.

Economic stabilization is equally critical. The current sanctions imposed on Venezuela will not unwind on their own. Currencies do not stabilize without confidence. Corruption does not recede without enforcement and institutions. Humanitarian relief and long-term institution-building are not charitable add-ons; they are essential to preventing collapse. Intelligence support must go beyond targeting to provide a deep societal understanding and continuous, candid assessments of stability and legitimacy—assessments that policymakers may not want to hear, but must.

The administration may consider rebuilding Venezuela after “regime change” as a kind of philanthropy, but if they do topple Maduro, they will find instead that it’s a necessary condition of removing U.S. forces and stemming the inevitable bleeding that will affect our hemisphere.

So far, Congress appears to have been sidelined in this operation. That cannot continue. Authorization, funding, and sustained political legitimacy depend on having the legislative branch on board. For all its faults, mistakes, and failures, the Bush administration put a lot of energy into amassing public support for the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq—and even then, that support proved soft when the public and Congress lost faith in the mission and those leading it. This administration appears to be doing even less to explain itself to the country, which could have dire consequences.

ONE OF THE MOST CONSISTENT FAILURES in regime-change planning is the absence of honest red-teaming, i.e., calculations of the enemy’s options to respond. Regimes facing existential threats do not capitulate quietly. They repress harder. They mobilize nationalism. They seek external patrons. They sabotage infrastructure. They create humanitarian crises that complicate intervention and fracture international support. Dense urban populations, of which Venezuela has plenty, increase civilian risk. Long coastlines enable smuggling and external interference, and Venezuela’s is 1,700 miles long, the same distance between Boston and Key West. Criminal networks embed themselves in political and economic life, and thrive when the government is dysfunctional. Armed paramilitary groups enforce loyalty through fear. Foreign intelligence services exploit chaos. None of these issues is hypothetical. These are predictable dynamics. Ignoring them does not make them disappear. It ensures surprise.

American leaders owe the public clarity about the risks they are willing to accept with any actions against Venezuela. Not precise numbers, but honest ranges. Not promises of gratitude by the Venezuelans, but acknowledgment of resistance. Not assurances of quick exits, but recognition of long commitments. History offers little support for claims that populations universally greet external regime change with enthusiasm—particularly in Latin America, where memories of U.S. intervention run deep.

Anyone advocating regime change in Venezuela is implicitly advocating for a long, bloody, expensive commitment—whether they acknowledge it or not. If the United States justifies regime change because it dislikes a government or covets resources, it erodes every argument it makes against aggression by others, such as Russia attacking Ukraine or the potential of China attacking Taiwan. Norms do not survive selective application.

The most important question is not whether regime change is desirable in the abstract. It is whether the United States is prepared—politically, militarily, morally, and financially—to own another country’s future for years. Clausewitz warned that war is a continuation of politics by other means. Regime change is the transformation of another country’s politics by all the means at our disposal. If ends are unclear, ways improvised, and means insufficient, the outcome is not strategy. It is a gamble.

In 2003, the surprise was not that Iraq proved difficult. The surprise was how little seriousness accompanied a decision that demanded extraordinary seriousness for over a decade, with the loss of life of our nation’s sons and daughters. If we are again unwilling to speak honestly about what regime change entails, then the responsible course is not to proceed cautiously—but perhaps to change course, or not proceed at all.