What’s Left of William F. Buckley Jr.

The conservative movement he built is now besotted with the kinds of characters and urges he repudiated.

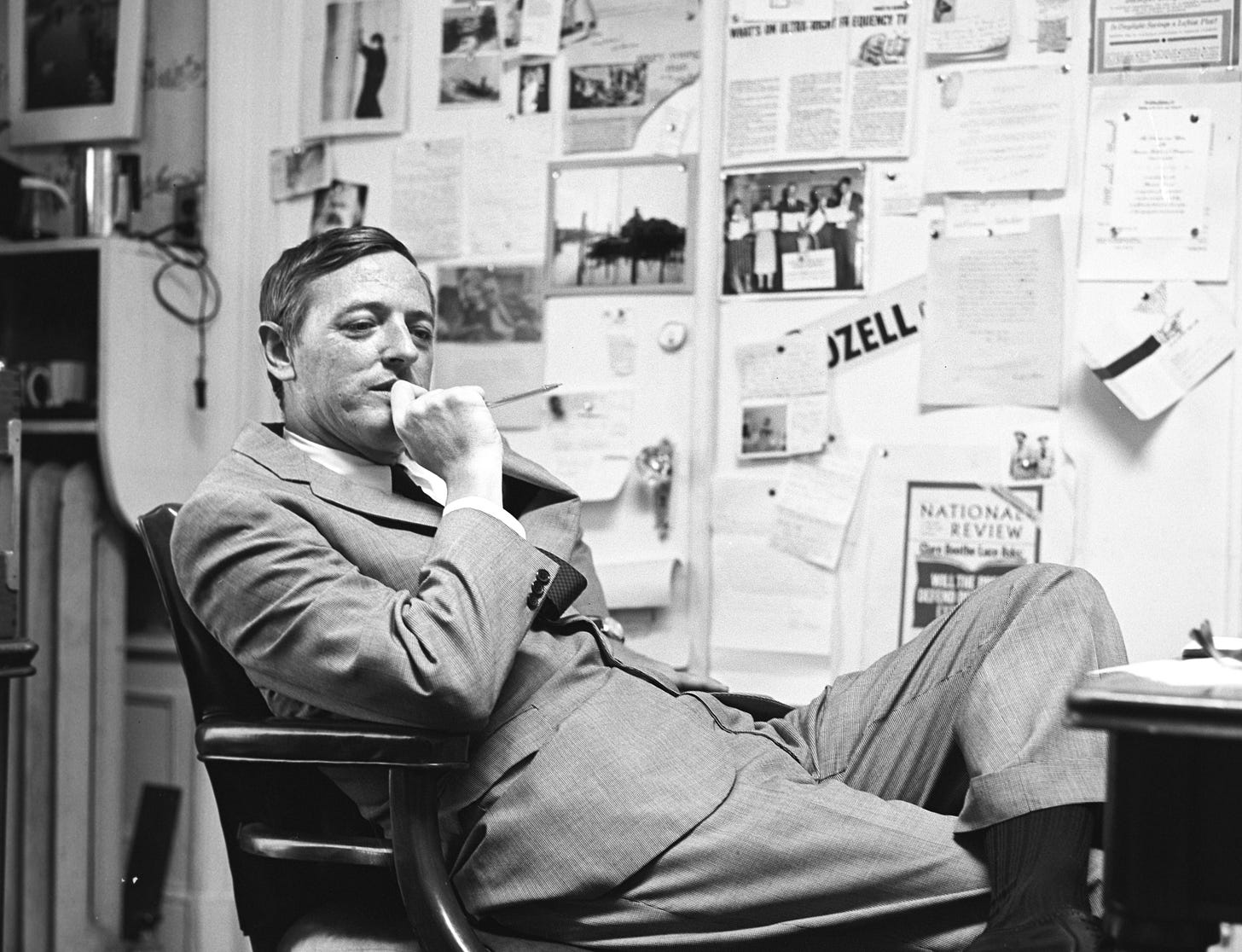

Buckley

The Life and the Revolution That Changed America

by Sam Tanenhaus

Random House, 1,040 pp., $40

THE AMERICAN CONSERVATIVE MOVEMENT is replete with ironies, perhaps none greater than this: The supreme sin on the American right today is the cultivation of intellectual and moral standards separate from the exigencies of power. The corollary to this prevailing nihilism is the impermissibility of any attempt to police one’s own side for cranks, crackpots, bigots, conspiracy theorists, and other unserious people—yet that is exactly how the modern American conservative movement started.

William F. Buckley Jr. is remembered today for having led the right out of the wilderness to real political power and cultural influence. But Buckley did not pull off this feat by simply establishing conservative dogma; he did it by showing that charm and magnanimity were some of the most useful armaments in the battle of ideas. In a similar vein, Buckley’s conservative triumph owed not only to his “honest intellectual combat” with the left, but to his decision to confront and expel the “irresponsible Right.” He is an apt figure to study and reflect upon at a time when leading conservatives exhibit scant charm while adopting a no-enemies-to-the-right policy—and when conservatism itself, as he would have recognized it, has ceased to be a force in American politics.

The initial seed for Sam Tanenhaus’s new biography of Buckley was planted by its subject ten years before his death in 2008, when he chose Tanenhaus to tell the authoritative tale of his life. Tanenhaus had made an impression on Buckley with his award-winning 1997 biography of Whittaker Chambers, the sour ex-Communist who emerged from his years as a Marxist-Leninist believing that the free world was doomed, and that the only “spiritual dignity left” to civilized men was “a kind of stoic silence.” Buckley never had any use for such shrinking detachment and was convinced that the resources of civilization were not yet exhausted, but he nevertheless adored Chambers and appreciated Tanenhaus’s account. The author was granted extensive interviews and exclusive access to Buckley’s private papers. The result is an absorbing but flawed chronicle of the firebrand who for decades was conservatism’s undisputed intellectual leader—a post that came into being with him and that arguably ended with him.

Admirers of Buckley will find more to quarrel with in these pages than his adversaries. Tanenhaus, no one’s idea of a conservative, undoubtedly appreciates Buckley’s wit and brilliance at the typewriter and on the debate stage. He lavishes praise on Buckley’s qualities as a wordsmith and polemicist and performer. But these are gifts, not virtues, and the author gives little indication that he esteems his subject’s character or principles. Although Tanenhaus readily admits that conservatism would have suffered immeasurably without Buckley’s presence on the ramparts, he leaves much doubt as to whether that beleaguered creed possessed any noble or ennobling content. His conclusion is nonetheless affecting:

A founder of our world, he speaks to us from a different one, beyond our reach but hovering near, if only we can discover in ourselves the imagination and generosity, the kindness and warmth, that Bill Buckley demonstrated time and again in his long and singular life.

BUCKLEY OPENS WITH A TERSE RECOUNTING of its subject’s upbringing in an immensely wealthy, conservative Catholic household. Billy, as he was known as a boy, spent his early years in Mexico and spoke only Spanish until age 6, then lived briefly in Paris before acquiring English in London at age 7. He also spent many seasons in South Carolina, which rounded off his mysterious and bewitching accent. This sprawling volume—nearly a thousand pages of text—traces Buckley’s 57-year career: founding editor of National Review, the conservative flagship and the twentieth century’s most influential political journal; syndicated columnist (penning some six thousand columns over his lifetime); TV debater; prolific spy novelist; belated booster of Barry Goldwater; mentor to Ronald Reagan; game-changing candidate for mayor of New York. If one seeks to understand the trajectory of American conservatism, there are worse places to start.

After some preliminary table-setting about the relevant family history—not skimping on the paterfamilias, the Texas oilman and devout reactionary William F. Buckley Sr.—Tanenhaus depicts the early germination of Buckley’s rebellious spirit. At age 7, Buckley supposedly penned a letter to King George V caustically suggesting that His Majesty repay Great Britain’s overdue war debts to the United States. A few years later, such nationalist stirrings prompted Buckley to become an America Firster.

Buckley’s dalliance on the isolationist right is well wrought by Tanenhaus, who conveys the provincial character of the movement that, in the midnight of the century marked by the Hitler-Stalin pact, was determined to keep America out of “foreign wars”:

W. F. Buckley [Sr.]’s view, and thus his children’s, was that America’s business with foreign nations should be restricted to business in the most literal sense: trade and investment of the kind Buckley Sr. himself had pursued throughout his career. Jumping into foreign wars, especially in the spirit of crusading interventionism of the kind Woodrow Wilson had embraced first in Mexico and then in Europe, could bring no good result.

In 1940, with the Japanese empire sweeping across Asia, and after the Nazi blitzkrieg had overrun most of Western Europe and was threatening Great Britain, the America First Committee formed to block military aid to London. President Roosevelt was sympathetic to the British cause, as was the Republican standard-bearer, Wendell Willkie, despite leading a party dominated by isolationists.

Without indulging the darker side of a movement that peddled antisemitic bigotry and lurid conspiracies, the young Buckley was suspicious of the Lend-Lease arrangement that dragged America closer to war. He also plainly nurtured an admiration for Charles Lindbergh, who was not only an antisemite but fraternized with Hermann Göring. Buckley’s first public speech, “In Defense of Charles Lindbergh,” delivered in February 1941, was an apologia for the famous pilot and leader of the isolationist faction. Moved by Anglophobia rather than antisemitism—the twin antipathies behind America First—Buckley defended Lindbergh as “the consummate patriot” and “the great advocate of American peace” (if not anyone else’s).

Buckley’s “first political cause,” Tanenhaus relates, “ended on December 7, 1941, two weeks after his sixteenth birthday, with the attack on Pearl Harbor.” Although the America First Committee immediately disbanded, Buckley wrote a letter to Lindbergh expressing his gratitude for “following the dictates of your conscience, in opposing energetically the demagogic cause.” To the Buckley clan and other anti-interventionists, the war effort would be, in Tanenhaus’s phrase, an “ideological extension of the New Deal” and tempt America into becoming an imperial power. Tanenhaus grants that this premonition would come to pass.

Buckley joined the Army, though the war terminated before he was ever deployed. After being discharged from “inactive duty,” he enrolled at Yale, where his vestigial isolationism yielded to a fierce anti-communism. So much of Buckley was at work in this metamorphosis, including both his conservatism and his radicalism. It was the first clue that his life would be a study in evolution: the America Firster who became a principled champion of U.S. global leadership, the apologist for Jim Crow who later yearned for the election of a black president, the self-described libertarian who agitated for the deconstruction of the New Deal but who fully embraced a former New Deal Democrat by the name of Ronald Reagan, whom he called the “incandescent embodiment of conservative ideals.”

But before all that, Buckley found himself out of place in the Ivy League establishment. He chafed against its fossilized liberalism that exhibited hostility to Christianity and capitalism in equal measure. He developed an idiosyncratic philosophy under the tutelage of the reactionary political scientist Willmoore Kendall and honed his polemical talents as chairman of the Yale Daily News. Vowing that there would be “no squeamishness about editorial subject matter,” the young editor piqued the administration by skewering unexamined progressive orthodoxies.

As his prominence grew on campus, Buckley called in a little-known speech for “a brigade of intellectuals” to halt the growing trend toward atheism and collectivism, and to “preach American principles and natural rights and divine sanction.” Soon after, he fleshed out this argument in a critical and commercial hit, God and Man at Yale. With this coruscating attack on his alma mater, 25-year-old Buckley announced himself as an intellectual force in American politics, which he remained until his final breath.

TANENHAUS SKILLFULLY RECREATES the historical predicament besetting conservatives in postwar America. When Buckley set out, conservatism was an inchoate creed, lacking the coherence of New Deal liberalism. Lionel Trilling was not exaggerating by much when he wrote in 1950 that “in the United States at this time liberalism is not only the dominant but even the sole intellectual tradition.” The country possessed a conservative impulse, he admitted, but this expressed itself in “irritable mental gestures” rather than full-fledged ideas.

To knit together a disparate collection of regional programs into a truly national doctrine required calculated effrontery and intellectual firepower in equal measure, as well as a dash of élan. For many Republicans, the progressive ideological compass of the era was agreeable enough. “The conservatives’ problem,” as Tanenhaus summarizes Buckley’s thinking, “wasn’t their devotion to lost causes. The noblest causes often were lost. . . . The problem was different. It was a lack of faith and of fight.”

This was the impetus behind the creation of National Review. In 1955, in the magazine’s first issue, Buckley proclaimed that the magazine “stands athwart history, yelling Stop.” It has become perhaps Buckley’s most famous phrase—but possibly his most misunderstood. Taken in isolation, the phrase implies a Hegelian if not Augustinian view of history (he might have written “History”) in which to stand athwart the forces (or Forces) driving events is, while perhaps noble, ultimately doomed. This is a very Buckleyan playful paradox—one of which Chambers would likely have approved. In the context of the entire manifesto, Buckley’s meaning takes on a Burkean shade—the point of yelling “Stop” is for the productive friction it creates with an ossified liberalism. Despite Buckley’s swashbuckling rhetorical style, his mission was to be the brakes on social “progress”—but not the reverse gear.

The acerbic young editor had vaulting ambitions for the modest magazine, wanting it to serve as “the point of the spear” for an avowedly radical movement. He sought to rally a disciplined resistance to the liberal fashion of moral relativism that was then infecting both parties. But he would also bring a cosmopolitan flair to a conservative tradition that had long been parochial and philistine. “Radical conservatives in this country,” he wrote, “have an interesting time of it, for when they are not being suppressed or mutilated by the Liberals, they are being ignored or humiliated by a great many of those of the well-fed Right, whose ignorance and amorality have never been exaggerated for the same reason that one cannot exaggerate infinity.”

But it was Buckley’s campaign against the John Birch Society that cemented his reputation as a conservative gatekeeper. The JBS was a sordid outfit that accused President Dwight Eisenhower and various government officials of being “conscious” agents of Moscow. Buckley denounced JBS founder Robert Welch’s “false counsels” and reveled in quoting Russell Kirk’s response to Welch’s most notorious allegation: “Eisenhower is not a communist; he is a golfer.” (Had Kirk not been such a dogged reactionary, he might have added that Ike was also the former Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, which presumably counted for something.)

The paranoia, eccentricity, and nostalgia that once animated the conservative paradigm were profoundly ill suited to modern America, and these deformities came under withering assault from both National Review and Buckley’s TV show Firing Line. Buckley’s robust but halting effort to rid the right of its moral and philosophical impurities—to create what he dubbed in a 1970 Playboy interview “hygienic conservatism”—was never fully successful, but his restatement of conservative principles and provocations laid low what Henry Adams might have called the “nonornaments” of the old right—from Gerald Smith and his Christian Nationalist Crusade to the libertarian crank Murray Rothbard. Whittaker Chambers took to National Review to maul Ayn Rand: “From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding: ‘To a gas chamber—go!’” (Years later, Rand retorted that National Review was “the worst and most dangerous magazine in America.”) In this and so many other ways, Buckley’s new conservative establishment challenged the regnant philosophy of the left without being, as was once said of the old German ruling class, blind in the right eye.

ALTHOUGH BUCKLEY WAS, as Tanenhaus puts it, a “controversialist, not a thinker and still less a theorist,” he fashioned the new conservative movement out of three fractious components: traditionalism, libertarianism, and anti-communism—the last of these being the glue that held the right together during the long twilight struggle against the Soviet empire. Free-marketers opposed the Red Menace for being anti-capitalist, social conservatives because it was hostile to religious faith, and mainstream conservatives because it threatened the American way of life. Buckley’s enterprise effectively “reduced the old Republican Party to ruins,” Tanenhaus notes. “But he had also willed a new one into being.”

In this effort, Buckley forged a cordial alliance with the neoconservatives. Near the midpoint of the Cold War, the United States was engaged in an ugly war in Vietnam, and American society was gripped by a wave of crime and political violence. These converging crises, along with the excesses of the 1960s counterculture, led these ex-leftists to migrate rightward. It has been said that you can define a conservative by what year he or she wants to go back to. The neoconservatives did not seek the repeal of the New Deal, but were skeptical of the efficacy of the Great Society. And while Buckley was a latecomer to civil rights, the neoconservatives were early and forceful foes of racial segregation. They formed a united front with mainstream conservatives in recoiling from the boundless growth of the federal Leviathan and progressive agitation for America to abdicate its international position.

Buckley earned credit with neoconservatives by softening National Review’s criticism of Israel after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War. The Jewish state’s success on the battlefield against Soviet-backed Arab armies greatly impressed Buckley, who even proposed, “not wholly in jest, the ‘annexation’ of Israel ‘as the fifty-first American state.’” By the time Buckley served as a delegate to the United Nations under the Nixon administration, he was not the “sworn enemy of the UN and its vision of universal human rights” but rather a loving critic. He even produced a first-rate memoir of his efforts to bring liberal democratic ideas and militant anti-communism to bear in the world body.

Though not true in every case, it seems in retrospect that most of the neoconservatives were liberals who, disillusioned by the disappointments of liberalism’s highest aspirations, favored many of the same policies as the conservatives, but without necessarily sharing their traditionalist and nostalgic inclinations. Where Buckley fit between these camps was sometimes hard to discern, which helps explain why he could unite them. In Tanenhaus’s telling, it’s also possible that Buckley moved over the course of his long career from one camp toward the other.

This evolution became pronounced in Buckley’s resentment at the way that President Lyndon Johnson, of all people, came under challenge from a minority of Democrats in the New Hampshire primary of 1968. He burnished what Tanenhaus approvingly calls his “emerging identity as a traditional, rather than radical, conservative” by impugning this display of “plebiscitary government,” which he defined as “instant guidance by the people of the government.” “A radical conservative,” Tanenhaus notes, “might welcome this disruption, which could only divide and weaken the Democrats.” But in the revolt of what became the New Left, Buckley detected an “unsettling” portent of a new political order “subversive of freedom.”

The union of the intellectual conservative and neoconservative camps resulted eventually in the Reagan Revolution. “Of a sudden,” observed Democratic Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1980, “the GOP has become a party of ideas.” In one fell swoop, Trilling had been overturned.

Early on, though, the salience that conservatism placed on the cohesion and continuity of society involved Buckley in some nefarious causes. The high strategic and spiritual stakes of the Cold War led him to defend Joseph McCarthy despite the Wisconsin senator’s scowling vulgarianism and manifest slovenliness. Buckley was always more invested in thwarting the Communist infiltrations of the McCarthy era—and exposing many liberals’ consoling delusions about them—than in McCarthy himself, but this cause demanded sharp-eyed vigilance, not curdled resentment and a penchant for conspiracy thinking. Buckley’s lifelong admiration for Francisco Franco emanated from his devout Roman Catholicism and his deep distrust of democracy. His apologias for apartheid rule in South Africa arose from similar sources. Both these commitments were unequivocally disreputable.

But it was Buckley’s opposition to the Civil Rights Act that discomfits Tanenhaus most of all—and properly so. Although more nuanced than mere white supremacism, Buckley’s atavistic sympathy for the peculiarities of the South begat a shockingly illiberal bias against legally enforced integration. Buckley initially believed that the South would desegregate on its own and that federal coercion was both unconstitutional and counterproductive. This conceit that state-enforced civil rights would traduce libertarian principles led Buckley to pen a notorious 1957 editorial, “Why the South Must Prevail,” that is justly scorned: “In a life dedicated to controversy,” Tanenhaus laments, it “haunts his legacy and the conservative movement he led.”

Tanenhaus also points out the hypocrisy of Buckley and his allies, noting that National Review “might well have supported [the legislation] on the majority-rule principle and the Constitutional separation of powers, which granted Congress the authority to make the nation’s laws. But when it came to race, NR writers drew on a different set of ideas,” embracing the nullification theories of John C. Calhoun, an odd and extreme doctrine that ought to have been left behind in the antebellum South.

But “to live is to maneuver,” as Chambers liked to say, and Buckley later discarded these specious laissez-faire arguments and conceded that federal intervention to abolish Jim Crow was amply justified. In so doing, he proved that his congenital reverence for tradition had a limit, and would ultimately yield to the dictates of reason and conscience. This was evident in his undisguised contempt for George Wallace, whose pronounced populism and Southern-fried chauvinism left Buckley “repulsed,” as Tanenhaus reports. Buckley regarded the arch-segregationist as noxious—an unwholesome fusion, as he put it on Firing Line, of “racism, nationalism, and collectivism, which spells a kind of fascism.”

THE PRODUCT OF THOROUGH RESEARCH and sober reflection, Buckley manages to be highly affecting without being in any way pious or sentimental. Beyond its plodding recitation of a restless public life, it is unsparing about its subject’s faults without omitting that saving quality that made Buckley a serious man: the courage to be eclectic and to evolve into an exemplar of the engagé intellectual. To paraphrase Lincoln, Buckley did not rely on the dogmas of the past when they proved inadequate to the needs of the stormy present. Even though he called himself a radical conservative, it was his moral and intellectual sense of prudence that undermined his claim to be the leader of the new conservative elite he built—invented, even—which he referred to as the “tablet keepers.”

Although Buckley was never confined by the partisan contest of thesis and antithesis, he instinctively knew that it was only in that cauldron that one could forge a vital synthesis. In breaking the grip of isolationists on the right, and casting out sinister antisemites and conspiratorial kooks, Buckley proved that his brand of conservatism was not a negation of the liberal tradition but rather a form of dissent within it. This could have been made reasonably clear from the text if Tanenhaus had not let his own partisan prejudice get in the way, and if he had given more than perfunctory mention of Buckley’s disgust at Patrick Buchanan and the residual antisemitism that was festering, then as now, on the populist right.

For Buckley, the historical responsibility of conservatives was altogether clear: to offer a spirited defense of America, of its beliefs and rights and institutions. This raison d’être eventually left Buckley out of harmony with the conservative mainstream. With the ascendancy of an expressly anti-liberal and anti-intellectual right, Buckley’s mature and metropolitan one-nation conservatism seems to have outlived him by only a few years, which subverts the notion of a “revolution” that “changed America” proposed in Tanenhaus’s subtitle. In reality, the contemporary right has reverted to many of its old and dismal habits, exuding intellectual frivolity and endorsing a callous red-hatted populism in all of its folly and fury. The right today has joined the age-old assault upon America, deprecating its system, impugning its honor, and abandoning its unique place among the nations of the Earth.

The right has now grown untethered from a traditional emphasis on moderation and prudence. Mainstream conservatives have been seduced by a shallow partisanship that has made them receptive to illiberal ideas and corrupt tribunes. They have lost the ability to discern sound conservative principle from grotesque contrarianism. Most alarmingly, they have lost the power to recognize, much less to ostracize, demagogues of all stripes. If Buckley’s task was to reconcile the best of the American tradition with modernity, the new right is stuck with the paradox of holding a philosophy—or at least the patina of a philosophy—of “conserving” and an actual order it does not want to conserve.

Buckley died in the middle of the 2008 presidential primaries. Tanenhaus notes:

None of the current Republican presidential contenders got in touch [with Buckley’s son, Christopher]. But two former Democratic nominees did: Bill Buckley’s fellow Bonesman John Kerry, with whom he had tangled over Vietnam, and Senator George McGovern, the victim of . . . Buckley’s needling columns. Bill and McGovern had recently met in public debates and discovered they liked each other.

When I was hired by National Review shortly after Buckley’s death, the American right was out of power and in the early stages of dissolution and crisis. Principled conservatism became dormant as Conservatism, Inc. succumbed to a strange ideological fervor that grievously wounded its political prospects as well as the public interest. In these dire circumstances, it became commonplace at National Review to hear lamentations along the lines that Buckley would be aghast to see what was becoming of his cherished movement.

At the time, I remember thinking that this did not ring true. Would Buckley really be so shocked by the growth of populism and illiberal nationalism and a creeping authoritarianism on the right? Surely, those afflictions in the late Obama years were hardly new, or any more daunting than they had been in Buckley’s time. The true crisis on the right, I believed, lay in the fact that it no longer had anyone of Buckley’s stature to keep the tablets. It still doesn’t.