Why Do We Accept Cormac McCarthy’s Self-Mythology?

Every writer creates an idealized narrative about themselves. McCarthy found a willing audience for his even though it obscures some facts about his life.

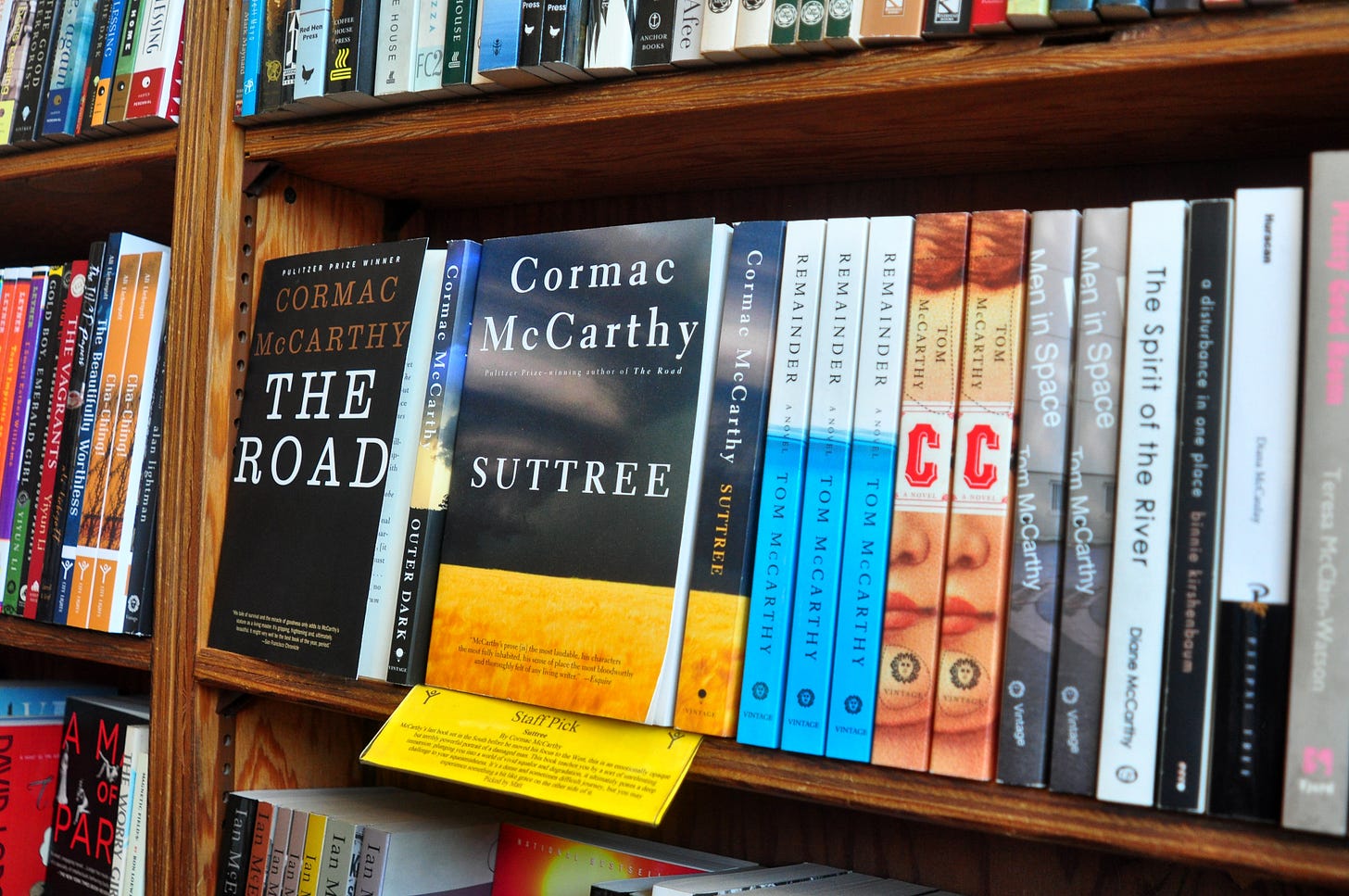

EARLY IN CORMAC MCCARTHY’S 1979 NOVEL Suttree, the narrator describes an unreachable, unknowable character as someone “glassed away in worlds of his own contrivance.” Following McCarthy’s death at 89 last month, obituaries have emphasized some of the starker features of the author’s own life in testament to the self-made world that set him apart from others. In a recurring parallel, the obituaries also noted that his reputation in American letters was, for decades, minor at best. As Dwight Garner observed in his writeup for the Times, McCarthy worked in “relative obscurity and privation” for many years; in the Washington Post, Harrison Smith described McCarthy as “plugging away at his novels without a care for their commercial prospects”; Christian Lorentzen, writing for the Financial Times, said that at most, McCarthy “gradually acquired the attention of a cult audience” in the first phrase of his career. And in the Guardian, Eric Homberger declared that “not since Faulkner had an American author been so extravagantly talented and, by choice, so distant from the literary culture.”

I agree about the talent —just not about the distance. Instead, I think our investment in framing McCarthy’s life and work in these terms reflects our own need for an artist who finally enjoys outsized success to have emerged from a prior longstanding obscurity, even if that’s not exactly true in McCarthy’s particular case.

To be sure, McCarthy eventually became one of the most prominent living writers in the United States, only then to avoid the expectations and accoutrements of a major elite writing life. No international reading tours or exotic festivals or fashionable big-city book parties for him, never mind prominent advocacy work or regular media appearances. When his 1963 Olivetti typewriter was auctioned for a quarter-million dollars in 2009, McCarthy donated the proceeds to the Santa Fe Institute, an interdisciplinary research center where McCarthy based himself in his final years. He continued writing on an updated model of the same Olivetti, which a friend bought for him for $20. All of this is consistent with the established narrative about the radical simplicity of McCarthy’s personal and writing life before the 1992 publication of All the Pretty Horses, which sold 100,000 copies even before it became a Hollywood movie.

Thereafter, McCarthy enjoyed consistent, outsized success as the author of demanding and difficult novels—his earlier books, including the legendary Blood Meridian, and the other novels of his Border Trilogy—as well as popular but harrowing later fare such as The Road and No Country for Old Men. Last fall’s publication of his final pair of books, The Passenger and Stella Maris, was a major literary event. Throughout these years of plenty, he was understood by the reading public as a hidden presence—“the most reclusive man in American letters,” Rolling Stone declared at the start of a 2007 profile, no doubt provoking angry letters to the editor from J.D. Salinger and Thomas Pynchon.

For those who had already been reading Cormac McCarthy for years before he came into wider notice, if while being consistently identified as a literary recluse, it was clear that he was writing novels out of a centripetal genius that united and built upon the work of Hawthorne and Melville, Faulkner and Hemingway. With faithfulness to this literary genealogy, McCarthy brought to his stories a sensibility that was governed by a Greek vision of fate, which typically overmatched recurring avowals of dignity and hope and sacrifice anchored in the Christian tradition. And he alternated between composing with crystal clarity and composing to achieve prose of portentous complexity; he helped create the latter effect by drawing from rarefied, abstruse vocabularies far removed from hodiernal life, as was he—and as his reading public liked to think he was, for our own needs.

CORMAC MCCARTHY WAS BORN IN RHODE ISLAND in 1933; his large Roman Catholic family relocated to a ten-room house on sizeable land in Knoxville after his father took up lucrative work as a lawyer for the Tennessee Valley Authority. McCarthy grew up in comfort. But as he made clear in one of his rare interviews—it’s compulsory to call all McCarthy interviews rare—he didn’t like the trappings: “I felt early on I wasn’t going to be a respectable citizen.” Indeed, he struggled in high school and dropped out of college twice; he spent time in the Air Force and worked in an auto-parts warehouse, reading voraciously during these lost years before writing and then publishing his first novel, The Orchard Keeper, in 1965. The book was acquired by William Faulkner’s final editor, Albert Erskine, at Random House, and it was awarded a first novel prize named after Faulkner himself. McCarthy had sent the book to Random House because, he once explained (to little skepticism), he didn’t know any other publishers.

But at this point his life took on a familiar pattern among rising literary writers: McCarthy went to Europe on an American Academy of Arts and Letters fellowship (Guggenheims and Rockefellers followed); he wrote his second novel, Outer Dark, while living on Ibiza, which has long been famous for its artistic colony culture. Meanwhile, the wider American literary world was certainly taking notice: McCarthy’s fiction won praise from the likes of Saul Bellow and Ralph Ellison and Robert Penn Warren; his pre-celebrity books were reviewed in the Times by prominent critics like Guy Davenport and Anatole Broyard; his third novel, Child of God (1973), occasioned an extensive essay by Robert Coles in the New Yorker. In what universe is this kind of early career—never mind the 1981 MacArthur “genius” grant that led to the 1985 publication of Blood Meridian, later hailed by Harold Bloom as “a canonical imaginative achievement, both an American and a universal tragedy of blood”—evidence of obscurity, or of being “distant from the literary culture,” or of having just a “cult following”? For that matter, how can it accord with McCarthy’s own sense of himself as lacking standing as a “respectable citizen”?

The claims supporting this narrative are deeply set in place, and have as much to do with McCarthy’s needs as with our own. I don’t begrudge him his: Every writer generates a story, usually multiple stories, of their life and work to justify both their successes and their failures along the way. I’m more interested in our eager acceptance of McCarthy’s version of himself—even our co-mythologizing with him—in establishing the dominant narrative of the writer-as-abject-demimonde-literary monk. I think the way the reading public and the figures who preside over it have agreed on the larger McCarthy storyline reveals a lot about how that public wishes to understand a writer’s life, and the tensions between family commitments and artistic principles and commercial success, and the ways we want these all things either to come together in a certain sequence, or to be set against one another in a zero-sum game wherein some things are privileged and some are sacrificed.

SHORTLY AFTER HIS AWARD-WINNING FIRST NOVEL was published, his first wife, Lee Holleman McCarthy, divorced him. The Washington Post last month reported her reason for going, quoting from her own 2009 obituary: McCarthy “asked her to ‘get a day job so he could focus on his novel writing’ even though she was already ‘caring for [their infant son Cullen] and tending to the chores of the house.’” Following his American Academy–funded time on Ibiza, McCarthy returned to the United States with his second wife, a British singer named Annie DeLisle. The couple lived in extreme conditions, in a dairy barn outside Knoxville in the early 1970s where, as DeLisle explained in an interview for a (rare) 1992 New York Times Magazine profile of McCarthy, “We were bathing in the lake. . . . Someone would call up and offer him $2,000 to come speak at a university about his books. And he would tell them that everything he had to say was there on the page. So we would eat beans for another week.” And McCarthy was living in a Knoxville motel—not a hotel, never mind a writing cottage at Yaddo or MacDowell—when he was informed that he’d won a MacArthur grant.

In other words, even while already enjoying standing and acclaim that the great majority of literary writers would find very welcome, even enviable, McCarthy disdained bourgeois security and made clearly selfish-seeming demands of those with whom he shared his life. But during these early years of voluntary destitution, he was also already publishing novels that the great majority of literary writers couldn’t match in ambition or achievement or critical attention or, for that matter, sales. It’s been widely noted that no novel of his sold more than five thousand copies before All the Pretty Horses began to sell tens and then hundreds of thousands; less widely noted, however, is the fact that hardly any novels of comparable difficulty, by any writer, ever sell more than five thousand copies. But instead of reckoning with such realities of literary work, we point to the wild extremity of McCarthy’s commitment to his writing—beans for dinner, lakes for baths, a motel room for home, three times divorced—and judge these privations as commensurate with the wild extremity of his aesthetic accomplishments and his later commercial success.

What do we get out of this? This standard framing of McCarthy both acknowledges and celebrates his commitment and its recompense, which is all well and good, but it also excuses and justifies the comparative lack of commitment and success among other writers. It also holds out the possibility of an eventual discovery or rediscovery, as with the romantic story we tell about Melville: death in obscurity; a Times obituary misspelling the title of Moby-Dick; the novel itself going largely unrecognized as a major work until the twentieth century. In his own lifetime, however, Melville enjoyed critical and commercial success with his early sea adventure novels Typee and Omoo—both spelled correctly in his death notice—but to point this out is to disrupt the more preferable underdog story, which gives hope to writers both great and not.

As for McCarthy, he acknowledged the costs of his commitment to writing in yet another of his rare interviews—no, not the 2007 interview with Oprah, the 2007 interview with Rolling Stone. He observed, “There is for a man two things in life that are very important, head and shoulders above everything else. Find work you like, and find someone to live with you like. Very few people get both.” The obvious implication is that McCarthy believed he wasn’t one of these very few people. Members of his family, in the early to middle stages of his career, doubtless wouldn’t disagree about the costs of his placing writing above all else. Yet near the end of his life, he seemed close to getting those two very important things. Already widely acknowledged as the era’s Great American Writer, the aging McCarthy worked out of the Santa Fe Institute. He would go to the office every day after dropping off his young son at school. Even if this vision of the writer’s life outside of writing strikes his readers as less romantic than the narratives of his earlier career, it is only here, I think, that McCarthy’s life feels more recognizable to most working writers. It is also more straightforwardly in line with Flaubert’s famous dictum, offered in an 1876 letter to a friend and patron, to be “regular and orderly in your life, like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.”

Cormac McCarthy was, at various points in his long life, both regular and irregular, orderly and disorderly. All of that, together, made it possible for him to be more violent and more original in his work than most of his contemporaries, and also more critically acclaimed and more commercially successful. He accomplished much, and he received much. The story of the deprivations he accepted for the sake of his work, and the purportedly low profile that work enjoyed for nearly three decades, informs and intensifies our appreciation for his achievements because it validates very American dreams about authenticity and commitment. At the same time, being more aware of the ways that story downplays and obscures parts of McCarthy’s life doesn’t require us to be cynical about what he did sacrifice and achieve. A fuller narrative still gives us someone who worked hard, ignoring many of the personal and interpersonal costs of his radical commitment; someone who eventually got what he deserved to earn, and then some; someone whose money and fame did not appear to change him; someone who kept writing great novels on a $20 typewriter.