Why Mark Kelly’s Case Matters

The action against him is unwarranted and could chill legitimate—and invaluable—public speech by veterans.

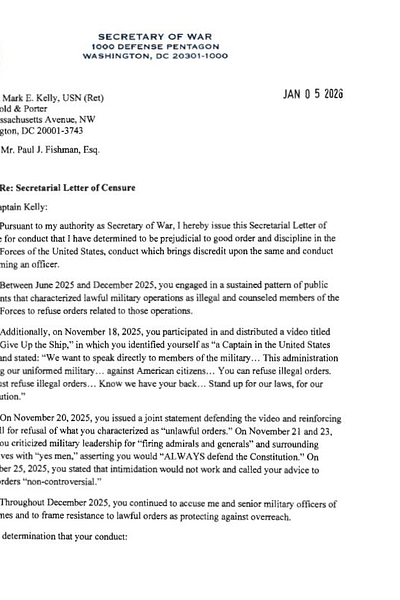

DEFENSE SECRETARY PETE HEGSETH has issued a formal letter of censure to Sen. Mark Kelly, a retired Navy captain, combat aviator, and astronaut. The letter accuses Kelly of conduct “prejudicial to good order and discipline,” threatens to reduce his pension, and warns that continued speech could expose him to further action under military law.

Kelly’s offense was to remind service members of a foundational principle of military law: Orders must be lawful—and illegal orders must be refused. That principle is not controversial. It is not partisan. It is not optional. He did this along with five other Democratic members of Congress who had served in the military or the intelligence community in a video titled “Don’t Give Up the Ship.”

Kelly did not urge service members to defy lawful authority. He did not name specific units that should disobey, nor list specific orders or commanders that should be disobeyed. He articulated a general legal truth—one that every commissioned officer has been taught, and one that even Secretary Hegseth has publicly acknowledged in the past.

The letter of censure attempts to recast Kelly’s participation in the video and other public statements as counseling disobedience on the grounds that Kelly might cause service members to “second-guess” orders deemed lawful by civilian leadership. But professional militaries require that judgment, primarily by officers but also by enlisted personnel. They train for it. They rely on it. They teach it in required classes and informally.

If merely reminding troops of their legal obligations constitutes misconduct, then we are no longer talking about good order and discipline. We are talking about intimidation.

I commanded soldiers for more than four decades. At every level—especially the brigade, division, and field army levels—before deploying into combat, I had conversations with soldiers, noncommissioned officers, company-grade officers, and senior leaders about lawful orders, illegal orders, and the moral responsibility that comes with wearing the uniform. Those conversations were neither rare nor improvised. They were deliberate, often in formal classrooms, with officers of the Judge Advocate General’s Corps.

That’s because every commander, at every echelon, works closely with Judge Advocate General officers to ensure that orders comply with U.S. law, the Law of Armed Conflict, and rules of engagement. Just as importantly, commanders are responsible for ensuring their subordinates understand their own obligations when faced with an unlawful order.

During one period in my career, as a three-star general, I led the Army’s Initial Military Training Command. My role was oversight of what was taught by drill sergeants in basic training for enlisted soldiers and advanced individual training, and the cadre who taught Basic Officer Leader Courses for newly commissioned officers and training for warrant officers. In every one of those courses the same lesson is reinforced explicitly and repeatedly: Obey lawful orders; refuse unlawful ones.

The range of types of unlawful orders are part of American military training, and may range from “Hey private, steal that can of paint from third platoon” all the way to “Lieutenant, shoot any enemy soldiers you capture because we can’t afford to take prisoners with us.” These training anecdotes are not framed as dissent, or adherence to any kind of subjective or personal standard. They are framed as a duty to do what is right, to live by the rule of law. The requirements are driven into young soldiers early because the cost of confusion later—under stress, under fire, or under moral pressure—is catastrophic.

This instruction is not accidental. It is foundational to professional military ethics. It is repeated early and often, and is especially important before deployments. The examples apply equally to active-duty, reserve, and guard officers, as well as retired officers. Rank does not absolve responsibility; retirement does not erase oath.

Which is why it is astonishing that the secretary of defense would now characterize a retired officer repeating this bedrock principle as “insubordination.”

Kelly is not just a uniquely experienced retired officer, having served in combat as a naval aviator and as an officer serving as an astronaut with NASA. He is a sitting U.S. senator and a member of the Senate Armed Services Committee. Questioning military operations, overseeing personnel decisions, and asking whether actions comply with domestic and international law are not acts of disloyalty—they are his constitutional responsibilities.

The attempt to punish him through military administrative mechanisms for something that was not a deviation from known standards is particularly troubling. It sends a clear message: Speak openly and plainly about the law, and your prior service may be weaponized against you. Kelly’s legal counsel has called it an unprecedented and dangerous overreach. From my professional military perspective, based on four decades of experience, I agree with that characterization.

Kelly is being wrongly accused of doing what the profession requires. If someone like Kelly—whose service record is unquestioned and whose statement was legally accurate—can be threatened with loss of rank and pension, then every service member should ask what protections remain when the rule of law and the requirement to follow only lawful orders become inconvenient to those in power.

Civilian control of the military is essential to democracy. The military must place trust and confidence in its civilian leaders. Likewise, the profession of arms also depends on trust—trust that orders are lawful, trust that leaders act in good faith, and trust that those who speak honestly about legal obligations will not be punished for doing so.

When telling the truth about the law becomes grounds for censure, the problem is not with the officer who spoke. It is with those who fear what the law requires. That is not a standard any democracy—or any professional military—can afford to accept.