Wisconsin Republicans’ Naked Exercise in Authoritarian Power

Gerrymandering GOP want to impeach a judge who threatens their control.

“DEMOCRACY IS A SYSTEM IN WHICH parties lose elections,” according to the political scientist Adam Przeworski. By that measure Wisconsin is not really a democracy.

Sure, the Republican Party of Wisconsin routinely is defeated in statewide elections. Indeed, since 2018, they have lost fourteen of seventeen such races. But can they be said to really lose when they refuse to accept their defeat and instead use power accrued by undemocratic means to minimize or even reverse those losses?

In this, Wisconsin was the pre-Trump canary in the coal mine, alerting us to the undemocratic depths to which the GOP would descend. The state’s Republicans then became bolder following Trump’s Big Lie example. Now they are threatening to impeach a newly elected justice on the state’s high court, Janet Protasiewicz, who has not heard a single case. Their rationale? That she had characterized the state’s election maps as “rigged.” Never mind that she’s right about Wisconsin’s highly gerrymandered districts; her election threatens their hold on power and they are growing desperate.

IMAGINE YOU ARE A VOTER IN WISCONSIN. Let’s say you want Medicaid expansion, a broadly popular policy. Wisconsin is now only one of ten states that does not have it, along with Wyoming and other deep-red states in the South. You vote for a governor who makes Medicaid expansion the centerpiece of his campaign. But as soon as he is elected, the gerrymandered legislature strips him of his traditional power of overseeing Medicaid.

The governor loses other powers, too. The legislature refuses to hold hearings for his cabinet appointees, and removes acting officials when they are critical of the legislature. Ultimately, the governor can use his veto pen to stop things from happening, but he cannot initiate change. He can call special sessions of the legislature on topics of public concern like criminal justice reform or abortion, but the legislature simply gavels in and out, refusing to do anything.

Or, speaking of abortion, let’s say you are unhappy with the 1849 anti-abortion law that comes back into effect after last year’s Dobbs decision. You are in the majority that favors maintaining broad access to abortion. But the legislature will not listen to you.

Fundamentally, state Republicans do not feel they need to respond to majority opinion—most clearly on abortion rights. And they are right, they can get away with being unresponsive—because of the gerrymander. It cements their huge majorities in both houses of the legislature. And this, in turn, makes judicial campaigns more politicized, since the judiciary becomes the only realistic venue where voters can expect a measure of democratic responsiveness. Your only real hope under these conditions is the state Supreme Court. They decide on key issues, like abortion access. And they are the only actor that can fix the source of democratic unresponsiveness: the gerrymander.

So you find a state Supreme Court candidate who agrees with you on abortion. She even calls the gerrymandered maps “rigged.” You vote for her. She wins by 11 points, a landslide in Wisconsin, amid record turnout. A victory, finally, for democracy.

Just one problem: The party that designed the gerrymander, and benefits from it, is threatening to impeach her if she dares rule on the case.

HOW BIG OF A DEAL is the gerrymander in Wisconsin? After all, since liberal voters are concentrated in urban areas, isn’t the Republican majority simply a function of geography?

This is partly true: Republicans really are advantaged by the geography of the state. But if the gerrymander didn’t matter, Republicans would not be fighting so hard to protect maps designed in secret by their political consultants.

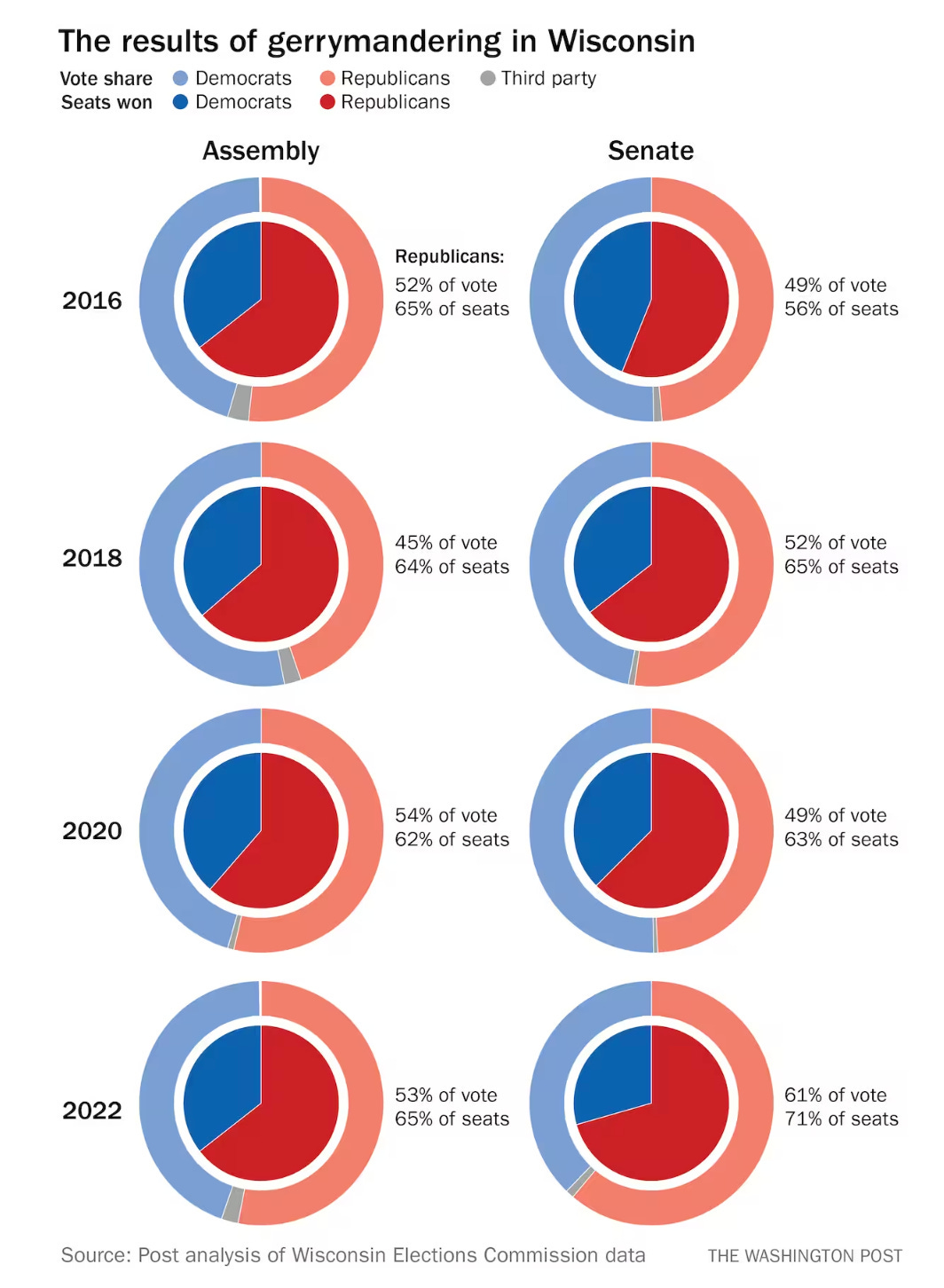

The overriding purpose of the gerrymander in Wisconsin is to maximize Republican votes. And in this, it is incredibly effective. Political scientists have come up with different models that consistently show how biased the maps are. The data visualizations produced by the Washington Post’s Philip Bump powerfully illustrate the point:

A party that routinely loses statewide elections has a supermajority in both the Assembly and Senate. Even in cases of Democratic wave elections, such as 2018, the outcome barely budges. Indeed, the maps are most effective at putting a floor under Republican losses in election years where they are overwhelmingly rejected by voters.

Jamelle Bouie puts it this way in the New York Times:

The gerrymandering alone undermines Wisconsin’s status as a democracy. If a majority of the people cannot, under any realistic circumstances, elect a legislative majority of their choosing, then it’s hard to say whether they actually govern themselves.

The problem with gerrymanders is there is no obvious way to fix them. Federal courts might intervene. Justice Anthony Kennedy had signaled for years in Supreme Court rulings that he might be open to overturning a gerrymandered maps if someone could come with a credible formula. People did, but the case got turned back anyway. The current Supreme Court is even less amenable, having in 2022 ordered the state supreme court not to impose a slightly less bad version of the 2010 maps after the 2020 Census. The legislature, which benefits from the status quo, won’t solve the problem. The only viable means of reversing an electoral system is to vote in a state supreme court majority that is likely to overturn the map. And now Republicans are taking this off the table.

WHAT IS GALLING about the whole thing is how much the basic claims against Protasiewicz are a flimsy pretext for the exercise of raw power to protect the gerrymander at all costs. Republicans are making up new standards as they go. Here are the facts:

Protasiewicz’s actions fall short of any constitutional standard or precedent justifying impeachment.

The state constitution allows for impeachment of judges in cases of corruption or commission of a crime. There is no real case that can be made on that count. And to give a sense of how unprecedented this action would be, the last judicial impeachment in the state occurred 170 years ago, for a lower-court judge who engaged in bribery.

Protasiewicz’s actions were not substantively different from those of other judges, including her opponent.

Everyone knows this debate would not be occurring if Protasiewicz’s opponent had won. Not because he was less political, but because Daniel Kelly was political for the right party. He was a paid consultant and legal adviser for the Republicans on election issues that he would have to rule on, he ran his campaign from state GOP headquarters, he worked for a former Republican governor who appointed him as judge, and he even defended the disputed maps in court.

Before running for the state supreme court, Kelly told reporters, “It’s a good map. It’s a solid map. It’s constitutional. It reflects the judgment of the people of the state of Wisconsin.” When former Milwaukee Sheriff David Clarke asked Kelly if right-wing voters should have to worry about whether he might not follow their wishes on gerrymandering and other issues, Kelly responded, “I don’t think you have to worry about that with me.”

This is the model of judicial neutrality to which Republicans say Protasiewicz should aspire.

Protasiewicz did not violate the Code of Judicial Conduct.

To give this coup an air of legitimacy, Republicans are saying that Protasiewicz violated some rules.

Here is the problem with that claim. The body that reviews ethical violations, the Wisconsin Judicial Commission, dismissed this complaint, pointing out that judges have wide range to express personal views without making a promise to rule in a specific way. Indeed, if previous writings or statements by judges that hinted at how they might think about issues that came before the court were grounds for violation, few of the sitting justices on the state’s high court would be likely to keep their seat.

One last ugly irony: Wisconsin Republicans apparently see no contradiction between their belief that Donald Trump should be allowed to run for president again despite trying to overturn an election and their belief that a judge should be forced out of office for having made some mildly pro-democratic comments.

THE REPUBLICAN PLAN for Protasiewicz may not actually be to impeach and remove her, which would allow Democratic Gov. Tony Evers to name her replacement. If they vote for impeachment in the Assembly, which requires only a simple majority, she would be prevented from actively serving on the court while the impeachment trial is pending in the Senate. But the state constitution does not specify what happens if the impeachment process is never completed; it assumes that legislators had good-faith intentions and that an impeachment trial will in due order follow an impeachment.

But Republicans are not in the good-faith business nowadays. They’re in the norm-busting business. And the Republicans in Wisconsin can follow the norm-busting example set by the Republicans in the U.S. Senate in the last few years, as when Mitch McConnell stonewalled the confirmation hearings for Merrick Garland’s U.S. Supreme Court nomination.

If Protasiewicz is left in limbo without a trial, the Wisconsin Supreme Court would effectively be down a justice, left with a 3-3 tie. Protasiewicz would have few options but to resign at this point, forced out without even the charade of due process that a completed impeachment process would offer.

Since Republican leaders proposed impeaching Protasiewicz, they have faced a national backlash and an aggressive Democratic state outreach campaign. Historically, this has not stymied their willingness to break norms, and Assembly Speaker Robin Vos said on Friday that his colleagues might proceed with the threatened impeachment process, at least if Protasiewicz does not “recuse herself on cases where she has prejudged.”

But Vos may now be looking for another way out. On Tuesday, he announced an “Iowa-style nonpartisan redistricting” approach that the Assembly might vote on this week. Vos and fellow Republicans have opposed this idea for years. Why the change of heart, and the speed? Vos apparently hopes that quickly passing the bill would remove the gerrymandering case from the courts in the first place. And the Iowa model allows the state legislature to reject the maps created by the nonpartisan commission and substitute its own. And so, the gerrymandered legislature is looking to remain the master of its own gerrymandered domain, having found a new way to cut a now-unfriendly court out of the process. Advocates for fairer maps, including Gov. Evers, swiftly rejected the Vos proposal, which indicates both how little trust there is and that the showdown over the maps will not be over anytime soon.

THE MISTREATMENT OF PROTASIEWICZ is hardly the only example of the Wisconsin GOP acting abusively to protect their political dominance. It is very much part of a broader pattern. Another example made headlines this week, as Republican state legislators are seeking to remove the administrator of the state’s bipartisan election board, Meagan Wolfe. On Monday, a Senate committee voted to remove her from office, and the whole Senate could vote to remove her as soon as this week. The state’s attorney general, a Democrat, has said this would not be legal, potentially setting up a clash that could go to the state Supreme Court.

Wolfe—whose plight Bill Lueders laid out here in July—is being punished for not going along with the Big Lie, for not entertaining the fantasy that Wisconsin Republicans won the 2020 election, and for imposing a set of electoral procedures that Republicans retrospectively decided disadvantaged them by allowing too many people to vote.

And so Wolfe’s fate is likely to be the same as the leaders of the Government Accountability Board; they were fired and the board disbanded in 2015 after they looked too aggressively into Republican Gov. Scott Walker’s campaign finance practices.

Or the leaders of the state ethics commission and the elections commission, who were removed from their positions in 2018 because they had worked for the Government Accountability Board.

In other words, Wolfe is discovering that it is impossible for a statewide election official to keep her job in Wisconsin if she is seen as an enemy to the Republican Party of Wisconsin, which at this point can be triggered merely by trying to ensure a functional election and refusing to embrace conspiracy theories.

I worked at the University of Wisconsin-Madison as a professor for 13 years, from 2005 to 2018. During that time the democratic health of the state steadily weakened. But the state is at a new and shocking low. The removal of a judge who threatens the existing power structure by calling for more democratic representation is the sort of things we associate with authoritarian regimes. And now we associate it with Wisconsin.