Reggie Oliver, Discovered Gem

A modern master of the short horror form.

Many years ago, I started an annual project on my blog called “The Kind of Face You Slash.” Every day in October, I wrote about a different horror writer, or writers, and reviewed a handful of short stories, occasionally one of the writer’s novels. So that’s 31 posts every October for several years. One of the pros of doing that project was that in order to find new material, my own collection of horror literature having been depleted by past Octobers, I would scout bookstores and buy the many annual “Best Horror of the Year” anthologies. This would turn me on to very good (and very bad) writers I’d never heard of before. One of the most rewarding discoveries of this self-imposed annual death march was the British writer Reggie Oliver, who was described again and again as the one of the greatest practitioners of the more-or-less classic English ghost story currently writing. I’d soon learn that his stories aren’t so easy to pigeonhole, but at the time that was good enough for me. And in reading about him, one story in particular raised my eyebrows. Based on the title alone, I had to read it.

The story is about an academic on his way to a seminar. Running a bit early, he decides to duck into a music store and browse their classical music section, such music being one of his greatest joys and obsessions. Not finding much of interest he decides to leave. On his way out, he sees a bargain bin full of classical music CD box sets. Flipping through those, he finds a box set that he can’t quite believe exists, even though he’s holding it in his hands. The title of the box set, and the title of the story, are the same: “The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler.”

By the time the narrator gets home, he is obviously raring to give this a listen. Oliver describes the second movement of one symphony, “2nd Movement, Adagio Maestoso, Sehr Langsam,” or the experience of listening to it, this way:

[It is] very slow, an orgy of sorrow, with wailing strings and heavy brass plodding along to an insistent pulse on the timpani. I sit down to listen. It is compelling in its monotonous way. The stifling warmth of self-pity engulfs me. I mourn my lost aspirations, to travel, to be a ‘writer,’ rather than a mere academic. I mourn the sterile tedium that has overtaken my marriage. There is a self-indulgent tear or two on my cheek as I drift into a doze.

It shouldn’t be lost on anyone that “sterile tedium” pretty well sums up the consensus opinion of Hitler’s paintings. Anyway, I’ll stop here, as “The Complete Symphonies of Adolf Hitler” is a fairly short story, only about 10 pages. But suffice it to say it’s my favorite Reggie Oliver story (note that this is another “evil text” story, the kind I have praised before).

His stories tend to be longer, in the range of 30 or 40 pages, such as the title story of his collection A Maze for the Minotaur. The jacket copy of the book describes the odd, revenge-focused story as being set in a nineteenth-century London brothel, and ponders why the women who work there are so afraid of one particular client whose only desire seems to be throwing jam tarts at them. When I read that, I became worried. I worried that Oliver had gone goofy on me. But then I read it, and no. The first scene that shows the man—elderly, rich, fat—indulging in his apparently only fetish, which the reader gets the sense is overwhelming to him, is quite terrifying.

While the girls wait—and all the prostitutes are roped into this situation when the Minotaur comes—the Minotaur (none of the prostitutes in the city know the man’s name) gets ready. This consists of stripping out of his clothes, wearing only a half-mask on his face, and twisting his hair into the shape of two horns, sticking out from his head. Then the session, what almost feels like a ritual, begins:

Meanwhile the Minotaur had picked up the plate of jam tarts and was hurling them in a frenzy at the passing girls. Then, quite suddenly, he gave a great roar, which was a signal for the music and dancing to stop. For a space of half a minute nothing could be heard in the room except the exhausted gasps of the dancers and Minotaur’s stertorous breathing. Effie, involuntarily, let out a little giggle, and went pink with embarrassment and fear. She knew that any indication that their activities had been somehow a source of amusement displease the Minotaur greatly.

It gets more graphic from there, and the main character, Mabel, takes center stage as she seeks revenge on the Minotaur, first by learning his identity.

So the story doesn’t go goofy, but the strange sexual desire at the root of it all, mixed with a classic revenge plot, makes for an odd reading experience. Even odder is another favorite of mine, another relatively short one called “Tawny.” This story is told entirely in dialogue. I’ve read plenty of stores told solely through dialogue, and even a few novels, but I believe this is the first horror story with this structure I’ve encountered. Briefly, two elderly women, Julia and Vicky, are gossiping about the birth of Julia’s grandson. This is at a party for the baby, possibly following some sort of religious ceremony. Their conversation consists largely of the kind of catty British humor I like so much (“I’ve never really met the husband. . . . Isn’t it Derek or something?” “I’m afraid it is”) before slowly transferring into one of Oliver’s wince-inducing, in the best way, stories. I’ve read “Tawny” twice, and when I was going through it the other day I remembered the grotesque climax, but I didn’t remember the paragraph that follows it. That paragraph takes the story from “very good” to “great”—it’s unexpected, baffling, and black as night.

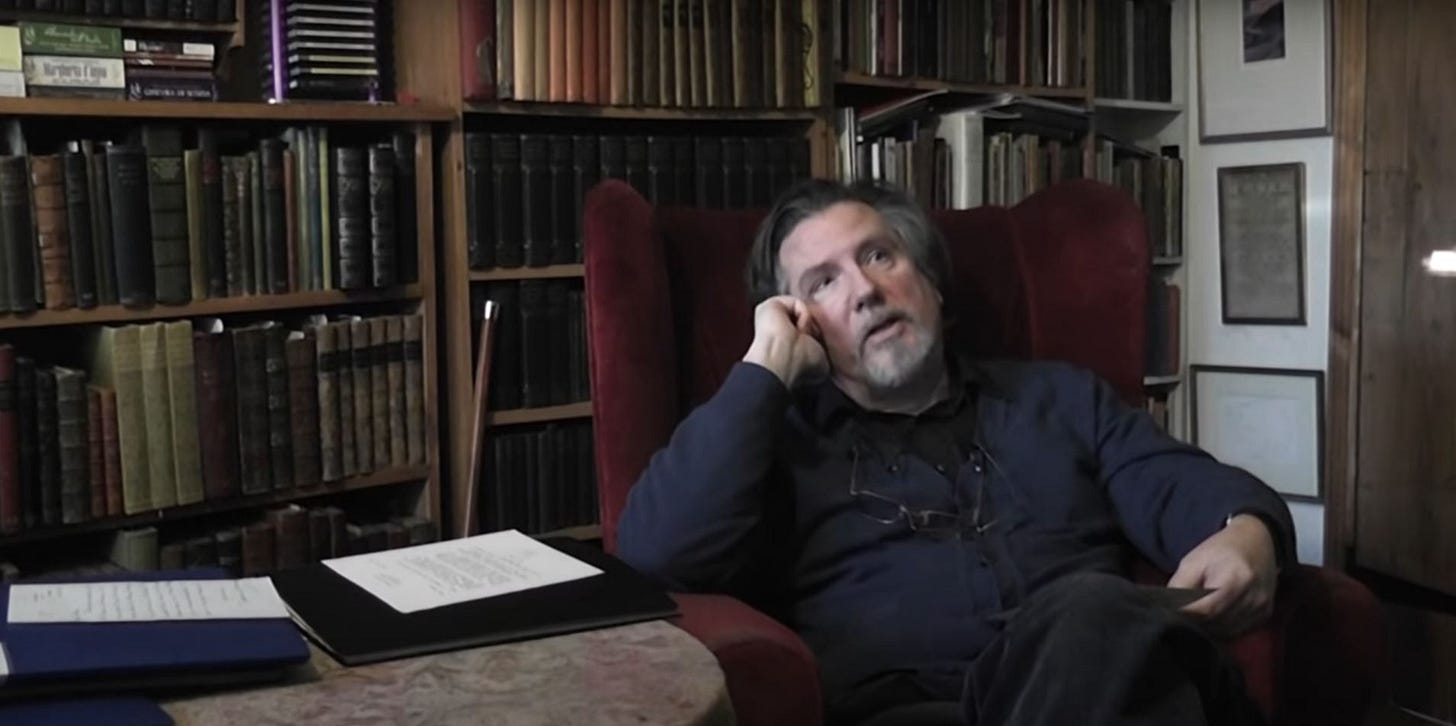

As perhaps you can see, the notion that Reggie Oliver writes classical English ghost stories is a bit misleading. Though not a mimic by any means, Oliver is rather closer to Robert Aickman than, say, M.R. James (there’s something rather akin to Aickman’s “The Swords” in “A Maze for the Minotaur”). Not surprisingly, in R. B. Russell’s short documentary about Aickman, Oliver features prominently.

Examples of this aesthetic fraternity between the two writers can be found throughout Oliver’s bibliography. In his “The Ballet of Dr. Caligari,” a minor composer named Charles May is tapped by legendary choreographer David Vernon to score Vernon’s proposed ballet version of the classic silent German expressionist horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Among Vernon’s requirements is that May ignore the film’s infamous framing device, demanded by the producers and reluctantly agreed to by the director Robert Wiene, in which we learn that the entire story was the dream of a mental patient. May agrees, and begins the job, though his relationship with the strict, cold Vernon becomes more and more fraught. Vernon’s plans for this ballet are obscure to May, but are clarified in a climax of horrible chaos. And though the idea behind Oliver’s ending is clear enough, the particulars are bewildering. A lot of “how” and “why” questions are bound to swim through the reader’s mind at this point, even if they otherwise “get it.”

Don’t mistake for clumsy, thoughtless writing, however. It is meant to knock the reader off balance, in the way Aickman’s fiction does. The major difference, I’d say, is that had Aickman written “The Ballet of Dr. Caligari,” he would have withheld even more.

Another story, “Holidays from Hell,” features a couple of stage managers (live theater is a recurring theme/setting for Oliver, who has also written several plays) arriving in a beach community, where they will be working on a show at the local theater. The simple version of what follows is that at the inn in which they’re staying live seven shadowy old people, whom the couple find vaguely disquieting even though they seemingly do nothing. At one point, the male narrator is in room with all of them and isn’t sure they’re even breathing. Later, the narrator is bitten by the landlady’s dog. After he recoils from it, the dog, Pluto, goes sniffing around the room for something, finds it, and brings it to our narrator:

At first it looked to me like a part of a doll. I reached for it slowly, tentatively, uncertain whether Pluto might not make a savage bid for its recovery, but he just stood there staring at me with his glassily malignant eyes. I picked it up and almost instantly dropped it. It was soft and cold, a real dead thing. It was a severed child’s hand.

But the story is at its strangest in the last couple of pages, and it involves the two stage managers simply witnessing something. They don’t understand it, the reader can take a stab at it if he or she likes. But the characters, outside of the man’s encounter with Pluto, are physically unharmed, not even really threatened, merely now burdened with this inexplicable, terrible event that they just happened to see, for the rest of their lives.

Reggie Oliver doesn’t just write horror stories. As mentioned earlier, he’s written several plays (comical ones, I’d wager, if the title Put Some Clothes On, Clarisse! is any indication); a biography of Stella Gibbons, author of Cold Comfort Farm; and a few novels. My understanding is that Virtue in Danger is a kind of adventure farce, while the other two, The Dracula Papers and The Boke of the Divill are explicitly horror. But he seems to know that horror fiction, or at least his brand of it, works best in the short form. Stretching “Tawny” out much longer would only hurt it, perhaps kill it. Reggie Oliver is a writer completely in control of his gifts.